Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

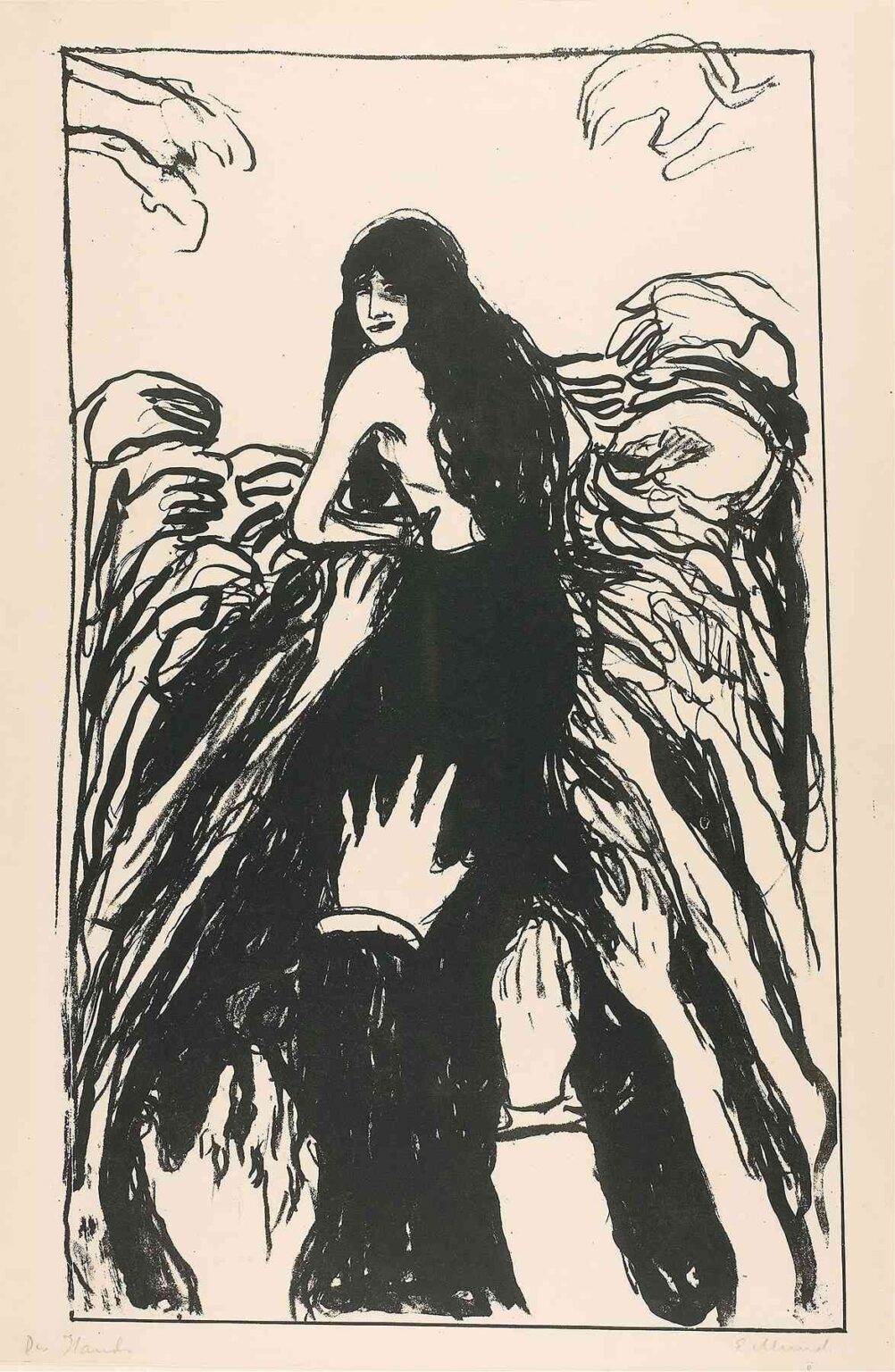

Edvard Munch’s 1895 woodcut “The Hands” presents one of the most visceral explorations of human anxiety and emotional upheaval in his graphic oeuvre. At its center stands a solitary female figure, her bare back turned to the viewer, as a multitude of disembodied hands reaches toward her from every side. Rendered in stark black ink against the pale paper, the print conveys both a claustrophobic sense of threat and a poignant vulnerability. Far from a mere exercise in technical bravura, “The Hands” distills Munch’s preoccupations with isolation, longing, and the inescapable pressure of unarticulated fears. In the sections that follow, we will examine how composition, gesture, medium, and symbolism coalesce to produce a work that remains powerfully resonant more than a century after its creation.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1895, Edvard Munch had established himself as a central figure of the Symbolist movement in Europe. The raw emotional intensity of “The Scream” (1893) and “Anxiety” (1894) had already launched him to notoriety, but also drawn criticism for their overt psychological content. During these years, Munch was deeply affected by personal losses—his mother died of tuberculosis when he was five, and his sister Sophie succumbed to the same illness in 1877. These tragedies fueled his fascination with grief and existential dread. At the same time, he immersed himself in printmaking, mastering woodcut and lithography as means to expand the reach of his imagery. “The Hands” emerged from intense experimentation in relief printing, a period when Munch sought to translate his painterly sensibility into the high-contrast drama of black-and-white media.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

The composition of “The Hands” is deceptively simple yet masterfully orchestrated. The artist frames the central figure—a young woman seen from behind and slightly turned—within an almost square field. Her long hair cascades down her back, bisected by the curve of her shoulder. Surrounding her, dozens of hands fan outwards in rhythmic clusters, their fingers splayed as if clawing or imploring. The hands occupy virtually every corner of the image, converging toward the figure’s body and enveloping her in an inescapable field of attention. Munch deliberately compresses spatial depth: there is no receding background, no horizon line. Instead, the plane of hands and figure occupies a single pictorial field, generating claustrophobia and intensifying the psychological drama.

Use of Form and Gesture

Gesture is the primary expressive tool in “The Hands.” The female figure’s posture—slightly hunched, head inclined—speaks of both resignation and awareness of her predicament. Her arms are drawn in, one elbow jutting slightly outward, suggesting a half-hearted attempt at self-protection. The hands, by contrast, are rendered with energetic linework: some are drawn with firm outlines and bold silhouette, others appear as faint sketches hovering at the edges. This variation in execution suggests temporal layering—some hands are closer, some more spectral—heightening the notion of persistent, intrusive thoughts. The upward thrust of each cluster of fingers echoes the organic curves of the woman’s hair and back, creating a visual dialogue between protector and threatened, self and other.

Color Palette and Monochrome Expression

Though devoid of color, “The Hands” achieves a remarkable range of tonal nuance through Munch’s handling of black ink on off-white paper. Areas of solid black—most notably the figure’s hair, the base of her skirt, and the deepest shadows between hands—anchor the composition and lend it weight. In contrast, thinner applications of ink create grayish passages that suggest depth and movement. The paper’s natural tone contributes warmth and softness, which tempers the starkness of the print and imbues the scene with an uncanny luminosity. By confining his palette to black and paper-white, Munch underscores the binary conflict at the heart of the work: self versus intrusion, concealment versus exposure.

Technique and Medium

Munch’s woodcut technique for “The Hands” departs from the highly refined tradition of Japanese ukiyo-e relief prints. He carved the block with broad, sweeping gouges, leaving the wood grain visible to impart a raw, tactile surface. His inking method—varying pressure and selectively wiping parts of the block—yields irregularities that amplify the sense of trembling, restless energy. In some impressions, the outermost hands appear ghostlike, barely touched by ink, while central shapes register as dense imprints. This painterly approach to woodcut exemplifies Munch’s innovative spirit: he treated the medium not merely as a means of reproduction, but as an expressive tool on par with oil or pastel.

Symbolism and Motifs

Hands recur throughout Munch’s work as potent symbols of longing, connection, and alienation. In “The Hands,” they assume a menacing vitality, emblematic of external and internal forces that assail the psyche. The absence of facial expression on the central figure intensifies her anonymity, inviting viewers to project their own experiences of intrusion or desire. Some art historians read the motif as an allegory for unfulfilled longing—a multitude of suitors competing for attention—while others interpret it as an embodiment of psychic fragmentation, where fragmented selves reach out in search of wholeness. Either reading underscores the hands’ dual nature: instruments of both comfort and coercion, extension of self and invasion.

Psychological Interpretation

Psychologically, “The Hands” articulates a universal tension between self-protection and the need for interpersonal connection. The myriad hands can be seen as representations of society’s expectations, familial demands, or the cacophony of one’s own thoughts. The figure’s turned head suggests awareness of the encroachment, yet her immobility conveys paralysis. In psychoanalytic terms, the print might register the struggle between ego boundaries and Id impulses—the compulsion to give in to external demands versus the instinct to withdraw. Munch’s own writings hint at the link between print imagery and his inner turmoil, making “The Hands” both a personal catharsis and a broader reflection on human vulnerability.

Relation to Munch’s Broader Oeuvre

While Munch’s painted canvases often employ color to express emotional states, his prints demonstrate an equally profound command of line and contrast. “The Hands” belongs to a series of woodcuts from the mid-1890s—alongside works like “The Voice” (1893) and “Anxiety” (1894)—in which he distilled psychological themes into stark, graphic form. These prints anticipate the Expressionist movement, inspiring artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde to adopt woodcut as a primary medium for subjective expression. Compared to his more famous paintings, Munch’s prints reveal an unflinching minimalism: they dispense with scenic detail to focus entirely on the raw energy of gesture and the psychological interplay of positive and negative spaces.

Reception and Legacy

At the time of its initial publication, “The Hands” circulated in avant-garde journals and as part of limited print portfolios. Critics noted its unsettling power but sometimes dismissed its graphic rawness as unrefined. However, collectors and fellow artists recognized its formal innovation and emotional impact. Over the decades, “The Hands” has been exhibited widely in retrospectives of Munch’s work, and scholars have praised it as a turning point in the history of printmaking. Its influence extends beyond fine art: twentieth-century poets, playwrights, and filmmakers have cited the image to evoke alienation, obsession, or psychic distress, cementing its status as a cultural touchstone.

Conservation and Provenance

Original impressions of “The Hands” are held in premier collections, including the Munch Museum (Oslo), the Museum of Modern Art (New York), and the British Museum (London). Conservation efforts focus on stabilizing the thin Japanese-style paper often used by Munch, which can become brittle over time, and ensuring the pigment remains adhered to the fibers. Scientific analysis—including infrared reflectography and microscopy—has documented Munch’s sequential carving and inking processes, revealing slight variations among impressions that testify to his hands-on approach. Provenance records trace early prints through private Scandinavian collectors to their eventual acquisition by major public institutions in the early twentieth century.

Broader Cultural Significance

Beyond art-historical importance, “The Hands” resonates in fields as diverse as psychology, literature, and design. Psychologists have referenced its imagery in studies of boundary dissolution and sensory overload, while writers have invoked its motif of invasive hands when depicting characters besieged by memory or desire. Graphic designers and illustrators cite Munch’s high-contrast compositions as foundational to modern visual language, where the interplay of positive and negative space conveys immediate emotional impact. In contemporary art, echoes of “The Hands” appear in installation works and digital media that explore themes of surveillance, consent, and the fragility of personal autonomy.

Conclusion

“The Hands” exemplifies Edvard Munch’s mastery of synthesizing profound psychological insight with formal innovation. Through the rhythmic convergence of gesture, stark contrasts of ink and paper, and the compelling anonymity of its central figure, the print captures the universal tension between intrusion and self-preservation. As both a milestone in the evolution of Expressionist printmaking and a deeply personal reflection on vulnerability, “The Hands” endures as a visceral testament to the power of graphic art to externalize inner experience.