Image source: wikiart.org

The Gulf of Color: Matisse’s Turning Point on the Mediterranean

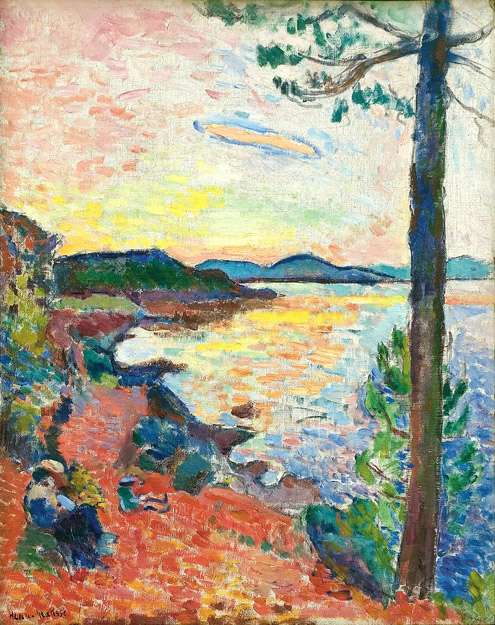

Henri Matisse’s “The Gulf of Saint Tropez” from 1904 records the exact instant when the artist’s painting begins to burn with a new intensity. The scene is simple—a rocky shoreline, a tall pine that cleaves the picture, a bay that gathers light like a bowl—yet the experience is anything but modest. Seen through bands of electric color and a lattice of quick, squared brushstrokes, this coastline becomes an experiment in how far color can go while still holding the world together. The painting stands at the threshold between Neo-Impressionist optics and the audacity of Fauvism, distilling the south of France into a grammar of saturated hues and breathing strokes.

Saint-Tropez, 1904: A Place Where Color Becomes Climate

Matisse arrived in Saint-Tropez at a moment when the town had become a magnet for painters searching for a pure, hard light. He met and observed Paul Signac and the Divisionists who parceled color into small touches to maximize optical brilliance. “The Gulf of Saint Tropez” takes that premise and loosens it. Instead of a strict scientific method of dots, Matisse lays down lively, tile-like strokes that vary in size and direction. The Mediterranean coast provided the perfect laboratory: cobalt shadows, copper rocks, citrus skies. In this place, daylight is not a neutral condition; it is a subject as tangible as a tree or a rock.

What the Eye Sees First

Stand before the painting and a series of sensations arrive in order. First is the vertical trunk that rises along the right side, a blue-violet column thickened by viridian accents and edged with sunlight. Next is the waterskin of the gulf, its surface cut into tremulous facets of lemon, salmon, and pale turquoise, suggesting sun sliding toward the horizon. Finally come the shore and rocks, a band of red-orange that zigzags forward, punctuated by bottle greens and cobalt shadows that give each boulder weight. The sky, stippled with warm and cool notes, reads as a ceiling of light rather than air: the world is made from color, not merely covered by it.

Composition as a Frame for Sensation

The composition is disarmingly clear. A tall pine tree establishes the near plane and anchors the right edge. The shoreline moves diagonally from the lower left toward the center, where it meets the horizontal of the distant headlands and the band of the gulf. This X-shaped structure sets up a stable scaffold within which Matisse can play freely with hue. The tree’s vertical mass counterbalances the gulf’s broad horizontal sweep; the zigzag of rocks creates a rhythm that carries the eye into space. With a few large moves, Matisse orchestrates movement and rest, then lets color do the detail work.

Drawing with Color Instead of Outline

One of the revelations of this canvas is how little linear drawing it relies on. The contour of the rocks is simply the seam where a hot red meets a cool blue. The edge of the water is a serration of complementary touches—yellow against violet, orange against blue—so that boundaries are precise without being hard. The pine trunk exists less as a silhouette than as a column of cool color that asserts itself against warmer neighbors. Form is negotiated through chromatic contrast; line becomes optional. This is drawing by temperature.

Divisionism Personalized

Matisse adopts the Divisionist insight that adjacent patches of pure color can create more brilliance than mixed paint, but he refuses to turn the mark into a formula. His strokes are not mechanically uniform; they speed up and slow down like breath. In the sky he uses shorter, closely set touches so the light hums; in the water the marks lengthen and align to suggest lateral movement; on land he thickens the paint and stacks the strokes so the ground feels crowded and solid. Divisionism becomes an instrument rather than a rulebook, tuned to the specific music of this motif.

A Palette That Makes the Air Glow

The palette is pitched high, but it is not random. Matisse builds the scene around a major chord of orange, yellow, and red opposed to a minor chord of blues and greens. The rock path engages the eye first with cadmium oranges and carmines, then cools at the edge where it meets the sea. The gulf is woven from pale citron, pearly pink, and ice blue, each laid next to its complement to heighten vibrancy. The tree holds a dark register—indigos and blue-greens—that keep the composition from floating away. Notice the absence of dead neutrals. Even the grays are mixtures that lean warm or cool, preserving the painting’s internal light.

Sunset as Structure

Although the vantage suggests late afternoon or early evening, the painting is less a transcription of a moment than a structure built to convey the sensation of one. The sky does not gradually fade; it steps from warm to cool in calibrated stages. The water does not simply mirror the sky; it refracts it, breaking the light into tesserae. The sun is absent as a disk, present only as a pressure that intensifies the yellow band near the horizon. Instead of describing atmospheric effects, Matisse constructs them, translating time of day into a pattern of hues that locks into place.

The Surface as a Field of Energy

The painting’s physical surface is as alive as its color. Paint sits on top of paint so that orange peeks through blue and blue through orange, creating a woven texture. In places the canvas breathes through the strokes, introducing a grain that catches light differently than the thick passages. The result is a vibrating field where no square inch is passive. This tactile liveliness is not decorative; it amplifies the sense of moving air and water. You feel the breeze in the resistance of the brush, the warmth in the assertiveness of the pigment.

Space Without Perspective Tricks

Traditional perspective would draw you into the scene with converging lines. Matisse chooses another route. He builds depth through color intervals: hot colors pull forward, cool colors recede, and value contrasts tighten as forms come close. The rocks in the foreground are sharply keyed; the middle distance softens; the distant headlands collapse into violet-blue islands. Depth is real, but it is achieved by relationships of hue and value, not geometry. This lets Matisse keep the surface articulate while still allowing your eye to travel.

The Pine as Protagonist

The tall pine is more than a prop; it is a figure. It stands between viewer and view like a thoughtful companion, placing you within the landscape rather than before it. Its cool trunk and tufted needles measure the light: wherever a strand of viridian meets a patch of lemon or coral, the intensity of the illumination becomes visible. The tree’s verticality also echoes the human scale, implying that the scene is one to be entered and inhabited, not merely admired at a remove. It is the painting’s measure of presence.

Rhythms and Counter-Rhythms

Look for how rhythms set up and cascade. The sawtooth edges of the shoreline repeat in the rock shapes, which repeat in the brushwork, which repeat in the scalloped cloudlets overhead. Against that pulse, the broad, still belt of golden water introduces calm—a kind of visual chorus that recurs whenever your eye returns to the horizon. This alternation of agitation and rest is what gives the painting musicality. It is scored to hold attention without exhausting it.

Echoes of Teachers, A Voice of His Own

The ghost of Seurat appears in the measured touch; the influence of Signac is present in the embrace of pure color and Mediterranean subjects. But Matisse refuses pointillist orthodoxy. He reintroduces gesture, allows strokes to swell, and accepts small dissonances if they heighten sensation. Where Seurat often seeks equilibrium through system, Matisse seeks harmony through feeling calibrated by observation. The painting records a conversation with predecessors that ends with a decision: method must serve joy.

A Prelude to Fauvism

This canvas anticipates the bolder Fauve canvases of the following year. The hot-cold collisions, the preference for color over modeling, the willingness to let local color yield to expressive need—all are here. What it retains from 1904 is a respect for optical play and a sensitivity to the specific place. The synthesis is potent: a picture that is both about Saint-Tropez and about painting’s capacity to generate light from pigment alone. When later Matisse turns fully “wild,” the seeds of that audacity are already planted along this shoreline.

Material Decisions That Matter

Even the practical choices are expressive. The relatively intimate scale intensifies the sensation of proximity; the close cropping of the trunk pushes the viewer almost to the lip of the path. The brush is loaded but not sloppy; passages of dry drag sit next to buttery impasto. These physical decisions carry meaning. Dry strokes flicker like sun on bark; thicker ones anchor weight. The varied facture prevents the optical shimmer from dissolving into sameness.

The Ethics of Delight

Matisse wrote and spoke often about art’s capacity to provide a kind of repose or relief—pleasure as an ethical offering rather than an indulgence. “The Gulf of Saint Tropez” enacts that conviction. Its luxury is the luxury of attentive looking, its calm derived from strong structure, its voluptuousness from the generous rhythms of paint. There is no narrative here beyond the event of light, yet the painting feels humane and hospitable. It makes room for the viewer’s breath to slow.

Comparing Kin: Studies and Variants

Place this painting alongside Matisse’s other Saint-Tropez works from 1904 and a constellation emerges. The picnic scene later titled “Luxury, Calm and Voluptuousness” shows figures testing similar color laws in a more populated Arcadia. “View of Saint-Tropez” spreads the town like a tapestry, a flood of light over roofs and water. “The Gulf of Saint Tropez” is the most focused of the set: no figures to distract, no town to explain—only the meeting of earth, tree, sea, and sky. It is the elemental chord from which the others take their harmonies.

How to Look, Slowly

To get the most from this canvas, alternate between two distances. Up close, track the working of the hand: the way a blue stroke is capped by a lemon flick, how an orange touch sits atop a duller underpaint, how the paint rides the tooth of the canvas. Then step back and let the system do its work; strokes fuse into light, complements sing, the path beckons. Repeat this dance. The painting is built for such oscillation, rewarding both analytic and sensuous modes of viewing.

Why It Matters Now

More than a period piece, “The Gulf of Saint Tropez” remains instructive for how it balances experiment and experience. It shows that innovation need not feel cold; that structure can underwrite, rather than stifle, delight; that a landscape can be both a place and a proposition about seeing. In a moment saturated with images, its sincerity is bracing. Every mark is there to make light happen. The painting argues—quietly but persuasively—that pleasure, when earned by rigor, is a form of truth.

A Lasting Afterglow

When you leave the painting, the afterimage is of yellow trembling on water and a dark, companionable pine steadying the blaze. That afterglow is not accidental; it is engineered through relationships of complement and rhythm. It is also the sensation Matisse will pursue for the rest of his career: color arranged to create a world that feels both composed and inevitable, intensely present and easeful. On this shoreline in 1904, he discovers not only the gulf’s shimmer but the path forward for modern painting.