Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

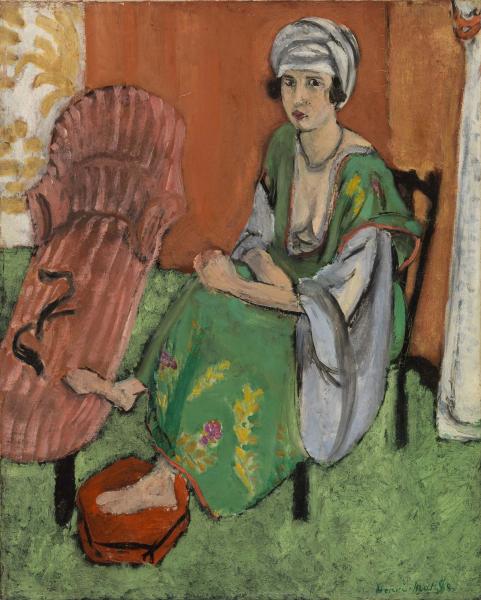

Henri Matisse’s “The Green Dress” (1919) captures a woman in a moment of unguarded domestic ritual. She sits on a dark chair in a shallow room, one foot bare and resting in a small red basin, the other leg half-covered by the hem of a vivid gown. A pink chaise longue tilts toward her at the left, strewn with a stocking and strap, while a warm terracotta wall presses forward behind her. The figure’s head is wrapped in a white turban, her neckline open, her hands collected at the lap as if pausing before the next gesture. The painting is intimate without being coy, decorative without surrendering to decoration alone. It exemplifies how, at the beginning of his Nice period, Matisse turned ordinary interiors into theaters of color, pattern, and poise.

Historical Setting And The Turn Toward Interiors

Painted just after the First World War, the work belongs to a year when Matisse sought renewal in quiet, habitable scenes. Rather than grand public spectacle, he favored rooms, balconies, screens, and women at leisure—subjects that could hold calm and concentration. In Nice he found a climate that softened light and let color bloom without glare. “The Green Dress” sits firmly within that pivot. It respects the gravity of recent history by refusing bombast, and it builds its dignity from compositional discipline: a figure, a chair, a chaise, a column of curtain, a carpeted floor. Nothing is extraneous; everything is arranged to create a steady, modern harmony.

Composition As Stagecraft

The room is designed like a shallow stage. A slanted chaise at left, the figure at center, and a curtain or column at right create three anchoring masses. The basin on the floor establishes a low circular accent, while the wall behind falls as a broad plane that contains the action. The figure’s pose generates a triangle from shoulder to knee to foot, a stable geometry that counters the chaise’s diagonal tilt. Matisse crops the chaise and curtain so that objects feel near and the space stays intimate. The eye is kept moving by the furniture’s angles and by the arc of the hem, but it always returns to the calm axis of the sitter’s face and torso.

Color Architecture And Temperature

Color does the heavy lifting. The gown’s saturated green dominates the field, tempered by floral notes and edged by cool gray sleeves. That green sits on a carpet of related hue, so the dress seems to breathe with the room rather than fight it. Against this cool expanse Matisse sets a terracotta wall and a pink chaise longue—two warm planes that infuse the scene with human temperature. The red basin under the foot concentrates that warmth into a small, intense circle, while the white turban, cuffs, and column introduce cooling relief. The palette alternates warm and cool across the canvas, a deliberate pulse that keeps the image lively without noise.

The Green Dress As Subject

Although a person sits in the center, the dress itself carries much of the painting’s meaning. It is generous in cut, with a deep neckline bordered by a gold-yellow insert, and with sloping sleeves that spill into pale, airy folds. The garment’s floral sprigs animate the broad green field with a few quick bursts of color. Matisse does not fuss over textile detail; he suggests embroidery with shorthand marks, preferring the overall rhythm of the cloth to minute description. The dress reads as a world in which the figure lives—a field of color that defines mood and grants the sitter gravitas.

Gesture, Psychology, And The Pause Between Actions

The woman’s posture is attentive rather than languid. One foot is in the basin and the other leg is drawn under the hem as she leans slightly forward, hands gathered near the knee. Her gaze meets the viewer, neither confrontational nor evasive, as if aware of being seen but not performing for the role. The stocking draped on the chaise, the strap or ribbon nearby, and the bare foot suggest she is in the middle of dressing or undressing. Matisse records the pause between actions, the moment when a person catches her breath and regathers herself. The intimacy is respectful; the scene preserves the sitter’s privacy even as it invites us into the room.

Furniture And Objects As Characters

The chaise longue at the left is more than a prop. Its shell-pink upholstery is ridged with wide brushstrokes that make the surface tactile, and its sweeping arm echoes the curve of the sitter’s shoulder. Because it is set at a strong diagonal, it thrusts into the picture like a companion entering the conversation. The red basin centers the foreground, a practical object turned into a chromatic anchor, while the white column or drape at right introduces a vertical counterweight. Together these pieces—chair, chaise, basin, column—behave like a cast, each with a color and line that contributes to the ensemble.

Line, Contour, And The Living Edge

Matisse’s contour is firm yet breathing. Black-brown lines wrap the figure’s limbs, cinch the neckline, articulate the chair, and trace the chaise’s profile. These lines swell and thin, opening in places to let planes meet softly and closing in others to assert crisp edges. The outline around the gown is not a fence; it is a pulse that keeps the color areas in conversation. The same lively outline appears in the chaise and in the column’s drapery, so that figure and setting are drawn with a single, unified hand. This shared contour makes the room feel coherent without becoming rigid.

Light And Surface

Light in this canvas is even and Mediterranean. There are few harsh cast shadows; instead, forms are turned by temperature shifts and by the direction of brushstrokes. The gray sleeves are a cool, nearly blue light; the chest insert warms to yellow; the terracotta wall glows softly and accepts the faintest flickers of highlight near the curtain. The paint sits with moderate body. On the chaise the bristles leave ridges that catch light, on the carpet the pigment is scumbled to reveal underlying tones, and on the dress broader strokes map the fall of cloth. These varied surfaces make matter legible without sacrificing the painting’s overall calm.

Space And The Modern Interior

Depth is shallow by design. The floor climbs the picture plane, the wall pressurizes the background, and the furniture overlaps just enough to suggest recession. This limited depth keeps attention on relationships at the surface—warm against cool, curve against straight, mass against void—rather than on perspectival illusion. The strategy is central to Matisse’s Nice interiors, where space is measured by pattern and color as much as by geometry. The result is a room that feels inhabitable but also unmistakably painted, a modern interior that admits both presence and artifice.

Ornament As Structure

Pattern in the painting is disciplined. The small floral bursts on the gown, the scalloped motifs on the chaise, and the suggestion of a palmette on the wall at far left all act as structural rhythms, not as frosting. They break large planes into readable beats and help steer the eye along designed paths. Ornament binds the picture the way a repeated melody binds a musical composition. Because the figure’s face and hands remain largely unpatterned, they emerge as resting points within this decorative field, keeping the human center intact.

Intimacy, Agency, And The Odalisque Tradition

The arrangement nods to the long tradition of the odalisque, yet it alters the terms. The sitter is not sprawled or exposed; she is upright, alert, and in control of her gesture. The open neckline acknowledges the body without theatricalizing it, and the bare foot reads as practical rather than provocative. By placing the figure in the midst of everyday objects—a basin, a strap, a chaise used as a surface for clothing—Matisse domesticates the odalisque mode and gives the woman agency within a private routine. The painting’s sensuality is warm and respectful, grounded in color and touch rather than spectacle.

The Turban And The Cosmopolitan Interior

The white turban crowns the figure with a note of cosmopolitan elegance. It adds a crisp, cool plane that clarifies the head’s silhouette and balances the warm wall. Matisse collected textiles and objects from North Africa and the Near East, and even when he paints domestic scenes he lets those influences filter into the room through fabrics, headwraps, and patterns. Here the turban functions less as ethnographic sign than as formal device: it lifts the figure’s height and concentrates light around the face.

The Viewer’s Path Through The Painting

A natural viewing path begins at the red basin, moves up the bare foot to the strong triangle of knees and hands, rises to the yellow insert at the chest, and then to the face framed by the turban. From there the eye travels along the curve of the chaise, notices the stocking and strap, and returns across the carpet to the figure. This circuit is both visual and narrative. It mirrors the sitter’s sequence of actions—shoe off, stocking gathered, basin readied, dress adjusted—and it confirms the painting’s stability: every route leads back to the green center.

Relation To Matisse’s 1919 Works

“The Green Dress” speaks closely to Matisse’s interiors and nudes of the same year. Like the reclining figures, it relies on a shallow stage, a few emphatic props, and a palette tuned to a single dominant note. Like the balcony scenes, it balances verticals and diagonals to keep the eye moving. Yet this work occupies a middle register between those modes: less languid than the odalisques, more anchored in everyday gesture than the balcony reveries. It underscores the Nice period’s breadth, showing how Matisse could orchestrate the same vocabulary—bold contour, large color fields, patterned accents—toward different emotional temperatures.

Material Presence And The Ethics Of Touch

One of the painting’s quiet pleasures is the way the handling honors each substance. The chaise reads plush because the brush digs visible grooves in its pink; the basin is enamel-bright with smoother curves; the carpet breathes because the pigment is rubbed thin; the dress falls with broad, confident sweeps. This attention to material character is not virtuosity for its own sake. It reflects a larger value: the belief that the dignity of a scene resides in how faithfully the painter observes and translates its feel. The room, the furniture, and the figure are treated with the same degree of care.

Time, Ritual, And Domestic Calm

Everything suggests a specific stretch of time—after returning indoors, before going out again, or midway through a morning of bathing and dressing. The stocking on the chaise and the basin at the foot are markers of duration; they imply what has just happened and what will happen next. Matisse avoids literal narrative and lets the objects carry that sense of sequence. The effect is a portrait of domestic calm, where the rhythm of small rituals grants the day its shape.

Why The Painting Feels Modern

The work feels modern not because of any shock value but because of its clarity. The figure is built from large, legible relations rather than from elaborate modeling; color is a structural force; black contour is unabashedly declarative; space is shallow and designed. These choices reveal the painter’s trust in essentials. They also keep the image fresh. The viewer encounters a room that is simplified but not impoverished, truthful without mimicry, elegant without fuss—a set of modern virtues born of restraint.

Conclusion

“The Green Dress” demonstrates Matisse’s gift for turning an ordinary interior into a poised orchestration of color and form. The gown’s field of green anchors the picture; warm planes of chaise and wall provide temperature; the white turban and column cool the edges; the red basin concentrates the scene’s pulse. Furniture behaves like characters, pattern operates as structure, and a respectful intimacy governs the human presence. In 1919, when the desire for steadiness was keen, such a room offered a vision of composure. Today the painting still communicates that promise: a life made luminous by attention to simple relations—body, garment, chair, and light—held together in a single, generous harmony.