Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Artistic Context

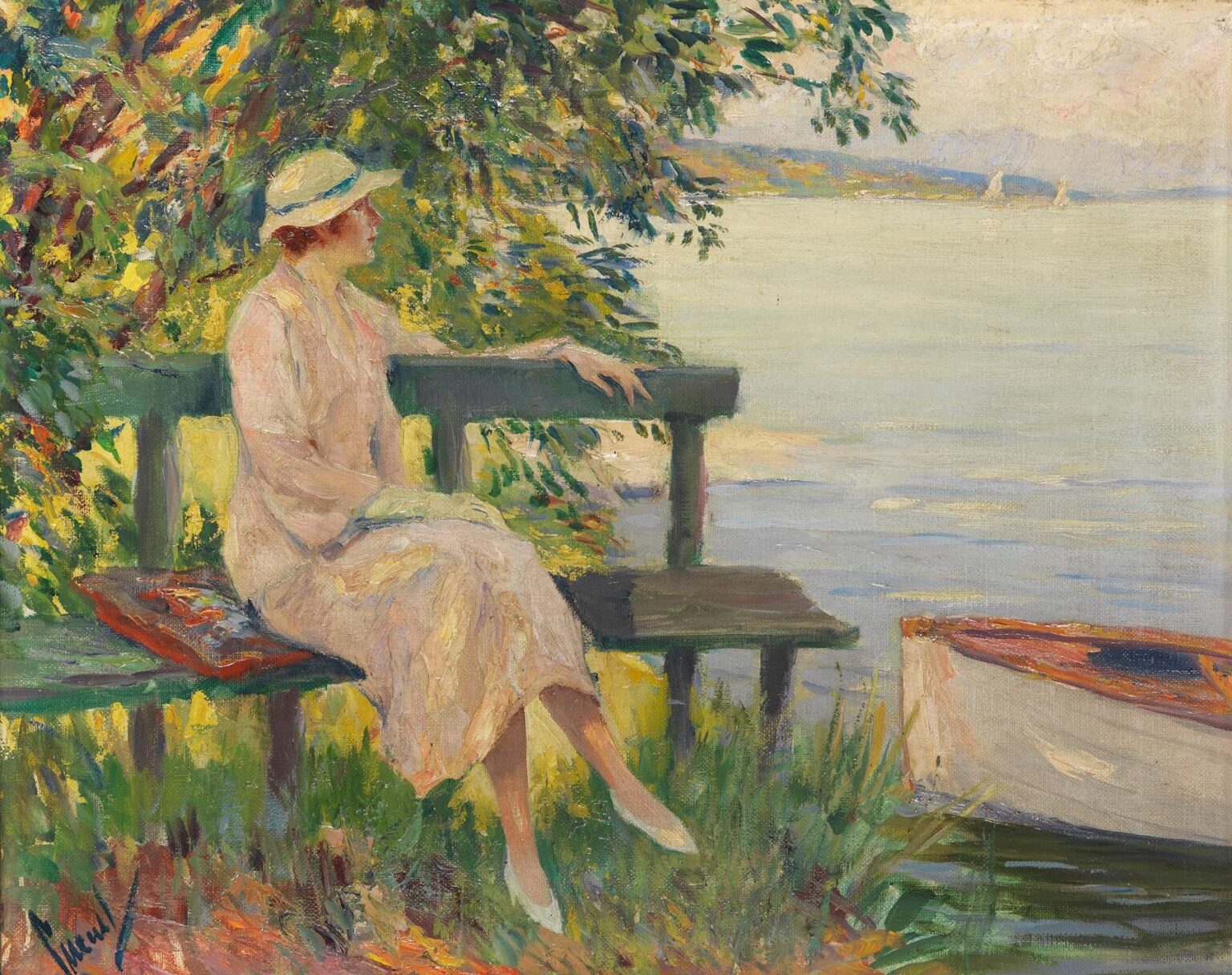

In 1920, Edward Cucuel painted “The Green Bench” at a moment when his reputation as a transatlantic plein air master was firmly established. Born in San Francisco in 1875 and raised in Stuttgart, Cucuel studied at the Stuttgart Academy before returning to New York’s Art Students League. His subsequent immersion in the Munich Secession movement and travels through Paris brought him face‑to‑face with the light‑driven innovations of the Impressionists. By the end of World War I, he had synthesized these influences into a mature style characterized by vibrant color harmonies, fluid brushwork, and intimate genre scenes. “The Green Bench” embodies his post‑war return to scenes of tranquil repose, celebrating everyday beauty in a world eager for renewal and serenity.

Setting and Composition

“The Green Bench” unfolds at the edge of a placid lakeshore, where a simple, weathered bench painted deep green sits partly in shadow beneath a generous tree canopy. A solitary woman, dressed in a pale peach day dress, occupies the bench, her arm draped along its backrest as she gazes toward the distant water. To her right, a small rowboat moored at the pier hints at a recent arrival or imminent departure. Cucuel arranges the scene along a gentle diagonal: the bench’s length leads the eye from foreground grass through the seated figure and toward the horizontal expanse of the lake. Overhead, the tree’s leaves form an organic arch that frames the woman and balances the composition’s linear elements. This interplay of horizontal, vertical, and curved lines creates visual harmony and guides the viewer’s attention through the painting’s key focal points.

Use of Light and Color Dynamics

Light is the sinew of “The Green Bench.” Cucuel captures the shifting interplay of sunlit patches and cool shade with a palette dominated by verdant greens, warm earth tones, and delicate pastel accents. The sunlit grasses in the lower left glow with golden yellow and lime greens, while deeper tones of emerald and forest green in the background foliage signal the tree’s cooling shadow. The lake’s surface reflects a soft, muted turquoise, transitioning to silvery grays near the horizon. The woman’s dress—a gentle blush of peach—draws its warmth from these surrounding hues, while her straw hat carries touches of ochre and soft white. Cucuel’s broken color technique, placing strokes of complementary hues side by side, achieves optical blending that makes the scene shimmer with the luminous quality of late afternoon light.

Brushwork and Textural Variety

Reflecting his plein air training, Cucuel employs varied brush techniques to animate different surfaces. The grass is built through short, stippled strokes that evoke its springy texture, while the leaves above are rendered with fluid, overlapping dabs suggesting a verdant canopy. The bench’s wooden slats and the distant boat are described with more linear, structured strokes, imparting solidity and man‑made form. In contrast, the figure’s clothing and skin are painted with smoother, blended passages that emphasize curves and softness. Subtle impasto in the sunlit grasses and highlights on the woman’s dress catch the viewer’s eye, creating a tactile presence. This tapestry of textures invites viewers to explore the painting both from a distance—appreciating its overall harmony—and up close, tracing the energetic paint surface.

The Figure’s Posture and Psychological Resonance

The solitary woman seated on the bench embodies a quiet narrative of contemplation and repose. Her body faces the water, suggesting an inward focus on the lake’s gentle expanse, while her head turns slightly, hinting at awareness of the observer. One arm casually rests on the backrest, the other lies in her lap, conveying both ease and graceful restraint. Cucuel’s decision to capture her in a moment of stillness—neither reading nor conversing—imbues the scene with introspective depth. Her downward gaze and the relaxed set of her shoulders evoke a mood of gentle melancholy or contemplative tranquility. Rather than presenting a static portrait, Cucuel renders his subject as a living presence, her inner life suggested by posture and gesture rather than articulated features.

Interaction Between Human and Environment

A key success of “The Green Bench” lies in the seamless integration of figure and setting. The green of the bench echoes surrounding foliage, visually linking human intervention with nature’s palette. The woman’s peach dress harmonizes with the golden sunlight filtering through leaves, as if her clothing absorbs and reflects ambient hues. The rowboat’s curved prow and the bench’s linear geometry mirror each other, reinforcing a dialogue between the lakeside environment and human presence. Cucuel’s portrayal suggests that the figure does not merely occupy the landscape but is an integral element within it—a participant in the natural rhythms of light, shade, and water.

Symbolic Undertones and Interpretive Layers

While “The Green Bench” reads as a tranquil lakeside study, it carries subtle symbolic resonances. Benches often signify pause and reflection—a momentary break in life’s journey—while the nearby boat hints at movement, transition, or freedom. The tree’s protective canopy suggests shelter and continuity, whereas the open water symbolizes vast possibility and the unknown. The interplay between shaded foreground and sunlit background can evoke life’s dualities: rest and action, security and exploration. Through this layered symbolism, Cucuel elevates an ordinary scene into a meditation on human longing, the passage of time, and the restorative power of nature’s embrace.

Architectural and Botanical Details

Cucuel enriches his composition with botanical and structural details that anchor the scene in a specific milieu. The tree trunk—broad, textured, and rooted in earthy tones—speaks to mature growth and enduring presence. Its leaves, hints of yellow where sunlight penetrates, contrast with deeper greens in shadow. The bench’s simple design—a backrest supported by sturdy posts—suggests rustic craftsmanship rather than ornate comfort, reinforcing the painting’s theme of honest communion with nature. In the distance, sailboats drift on the horizon, their white sails echoing the pale dress and hat, while distant landforms provide a soft blue‑gray backdrop. Each detail contributes to a cohesive sense of place that feels both specific and archetypal.

Compositional Balance and Negative Space

Cucuel’s mastery of negative space is evident in the right half of the canvas, where expanses of water and sky allow the figure’s posture and the bench’s form to stand out. This generous open area prevents the composition from feeling crowded, offering visual respite that mirrors the subject’s contemplative poise. Conversely, the left half—dense with foliage, grasses, and the tree trunk—provides visual counterweight. This balance of fullness and openness imbues the painting with dynamism, as the eye alternates between exploring detailed textures and resting on serene expanses of calm water.

Color Harmony and Chromatic Contrapuntal

Cucuel achieves rich chromatic harmony through carefully orchestrated contrasts. The deep greens of foliage find their complement in the warm peach of the woman’s dress, while flashes of red–brown earth beneath the bench resonate with small terracotta accents on the boat’s interior. The sky’s pale cream and blue‑gray near the horizon balance the painting’s overall warmth, ensuring that no single hue dominates. Highlights on the bench’s seat pick up echoes of surrounding colors, unifying disparate elements into a cohesive whole. Through such contrapuntal use of complementary and analogous hues, Cucuel imbues his scene with chromatic depth and visual cohesion.

Technical Execution and Materials

Painted in oil on canvas, “The Green Bench” showcases Cucuel’s refined material technique. The canvas was likely primed with a neutral, lightly toned ground, allowing subsequent layers of paint to maintain luminosity. Cucuel’s palette blends traditional pigments—lead and titanium whites, cadmium and ochre yellows, viridian and chromium greens, ultramarine and cobalt blues together with earth reds—for both brilliance and durability. His brush-handling alternates between wet‑on‑wet passage for dynamic color mixing and drier strokes for textural definition. Conservation reports note minimal craquelure and well‑preserved pigment, indicating both high‑quality materials and careful stewardship over time.

Provenance and Exhibition Reception

First exhibited in Munich’s Secession Salon in the spring of 1921, “The Green Bench” received acclaim for its luminous palette and evocative mood. Bavarian critics praised Cucuel’s ability to capture the restorative calm of lakeside repose, while his peers lauded the fresh spontaneity of his brushwork. The painting later entered a private German collection before migrating to the United States in the 1930s, where it featured prominently in retrospectives of American‐born artists who excelled abroad. Over the decades, scholars have recognized it as emblematic of Cucuel’s mature plein air style and his contribution to bridging European Impressionism with American sensibilities.

Comparative Analysis within Cucuel’s Oeuvre

Within Edward Cucuel’s broader body of work, “The Green Bench” stands alongside his other lakeside and garden studies—“Young Woman at Lake Starnberg,” “Spring Garden in Starnberg,” and “In the Shade”—as a testament to his enduring fascination with light filtering through foliage and the quiet pleasures of outdoor repose. Compared to earlier, more structured compositions, this painting reveals greater spontaneity in brushwork and a freer handling of negative space. Its mature tonal balance and narrative subtlety demonstrate how Cucuel refined his craft over decades, moving from academic precision to a more fluid, emotive approach that celebrates life’s simple yet profound moments.

Contemporary Relevance and Legacy

Today, “The Green Bench” resonates in a world hungry for respite from constant connectivity and urban stress. Its portrayal of solitary reflection by open water under a leafy canopy aligns with contemporary interests in mindfulness, forest bathing, and the therapeutic virtues of nature. As plein air painting experiences a revival among modern artists seeking to reconnect with natural light and gestural paint application, Cucuel’s work offers enduring lessons in balancing compositional structure with painterly freedom. His legacy endures in galleries and plein air workshops where artists continue to explore the interplay of light, color, and human presence in the natural world.

Conclusion

Edward Cucuel’s “The Green Bench” masterfully captures the luminous interplay of light and shade, the intimate bond between figure and setting, and the quiet eloquence of a solitary moment by the water’s edge. Through harmonious composition, vibrant yet balanced color, and expressive brushwork, Cucuel transforms a simple lakeside bench into a stage for contemplation, renewal, and poetic beauty. Over a century since its creation, the painting continues to enchant viewers—inviting them to pause, breathe, and savor the restorative stillness of nature’s embrace.