Image source: wikiart.org

A Garden Paused Between Nature and Art

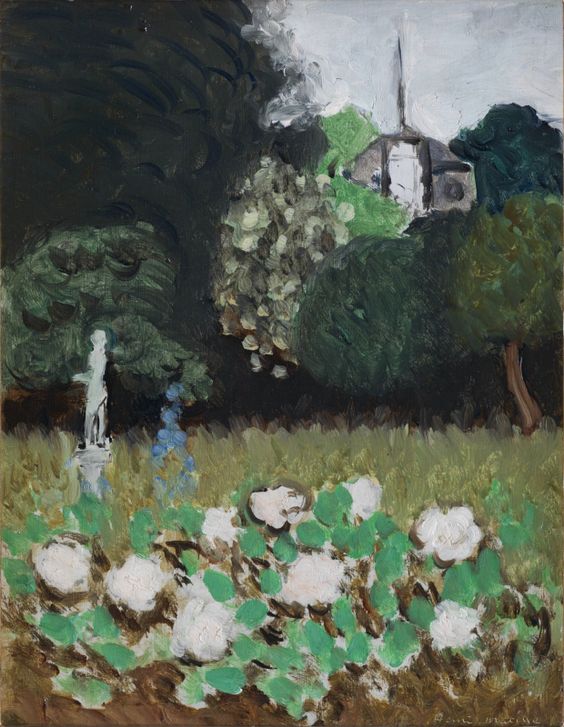

Henri Matisse’s “The Garden” (1920) welcomes the viewer into a compact world where living foliage and human making share the same calm air. Across the lower band, pale flowers ride upon thick, minty leaves like foam on a shallow tide. A narrow meadow opens behind them and gives way to a dark, velvety wall of trees. Within that shadow, a pale garden statue stands sentry, and beyond the trees a light-gray sky and a distant house with a slender spire rise like a quiet memory. The picture feels secluded and complete, a deliberate clearing where color, contour, and tempo are tuned to balance rather than bravura. Painted early in Matisse’s Nice years, it refines the wartime discipline of his 1916–1917 canvases into a serene garden grammar: fewer elements, steadier light, and a luxurious but controlled brush.

The Nice Period Setting and Why 1920 Matters

By 1920 Matisse had settled into the rhythm of the French Riviera, after several seasons of working in Nice. The change of climate and pace softened the palette, broadened the light, and drew the painter into spaces where interiors open onto terraces, balconies, and gardens. “The Garden” belongs to this search for serenity. It replaces the high-key theatricality of Fauvism with a measured spectrum of greens, grays, and earth tones, and it swaps bustling urban subjects for the restorative intelligence of plant forms. The painting stands at a hinge: it keeps the structural clarity and black contour of the wartime period, while anticipating the leisurely fullness of the Nice interiors and odalisques. You can feel in it a desire for steadiness—and an insistence that steadiness can still be full of life.

First Look: A Calm Structure with One Bright Edge

The canvas divides itself in three clear strata. The front band is a flower bed rendered as discrete paint-blossoms—thick, pale petals set among rounded green leaves and brown soil. The middle register holds a soft meadow, an olive-green pause that allows the eye to breathe. The top half is almost forest, a compact mass of trees that swallows light, then releases it along a ragged skyline where gray sky peeks through. Matisse plants one vertical accent to punctuate these horizontals: the white statue at left, slender and upright, which immediately calibrates scale and brings human measure to the leaf-world. The distant house and spire—small, crystalline, and held in cool whites—counterweight the statue and complete the sentence.

Composition as a Garden Architecture

Matisse lays out the composition like a gardener designing rooms. The flower bed is the parterre, close to the viewer and highly legible, stated with rounded, repeating forms that read at once from across a room. The meadow operates as a green allée, a transitional space that prevents the composition from becoming too dense. The tree mass is the garden wall, a living boundary that both encloses and focuses. Into that architecture he inserts two architectural motifs—the statue and the house—each pale and simplified, each allowing the eye to rest. The result is a plan as classical as it is casual: near, middle, far; ornament, openness, closure; human sign, living growth.

A Palette That Breathes Mediterranean Air

The color scale is narrow and confident. Greens dominate, but they are not one note. Sap, olive, bottle, and blue-green varieties shift with the painter’s wrist, so the field never clots. The flowers are creamy whites with warm centers, their volume suggested by the thickness of paint as much as by value. Tree shadows slide toward bottle green and nearly black, and yet they never deaden; they act as velvet, not iron. The sky is a mild, pearly gray that keeps chroma honest and lets the pale house with spire register cleanly. Against this climate of tempered color, the statue’s light value becomes a small flare, a necessary cool that lifts the whole scene.

Black Contour as the Garden’s Ironwork

Matisse’s mature language uses black as a constructive color rather than a void. In “The Garden,” dark strokes articulate the trunks and branches at the left and right margins and sketch a few rolling rhythms within the dense central foliage. These darks do the carpentry: they hold the mass together, keep the greens from dissolving into mush, and provide a frame that echoes wrought-iron gates and trellises you might find in an actual garden. Because these lines are flexible—thickening and thinning with pressure—they feel alive, nearer to calligraphy than to outline. They provide structure without strangling the paint’s breath.

Brushwork You Can Feel Underfoot

The surface is a record of varied touch. The front flowers are laid as rounded dabs—petal-shaped deposits that catch real light. Leaves around them are pushed with short, flat strokes, each one a little oval that overlaps its neighbor the way real leaves do. The meadow is swept with longer, softer passes that lean in one direction, as if a breeze were being noted without melodrama. The dark foliage in the upper register includes circular motions and feathered crescents, a kind of internal choreography that keeps the mass from feeling static. The house and spire are delivered with a few conclusive planes: no fussy detail, just enough to register. The statue is similarly succinct—milky, cool, a handful of planes that suggest form without modeling it to death.

Light as an Even, Democratic Envelope

The illumination is characteristic of the Nice period: broad, generous, and untheatrical. There is no single spotlight carving deep shadows or staging a dramatic narrative. Instead, light behaves like air—distributed evenly so that color can remain truthful. The flowers at the front are bright but not glare-white; the meadow holds a gentle sheen; the tree mass drinks light but does not hoard it; the sky is light enough to open the space without turning into a dominant field. This democratic light is crucial to the painting’s mood. It fosters steadiness. It lets the viewer look for a long time without fatigue.

Space Without Perspective Tricks

Depth in “The Garden” is achieved through overlap, value difference, and temperature shifts. The flower bed sits in front because its forms are largest and lightest. The meadow belongs to the middle because its tones bridge warm and cool and because its strokes are smaller and more uniform. The trees recede by being both darker and cooler; the house and spire, though pale, recede because they are held in the sky’s cool grays and because smaller scale locks them into the far band. The painting proves you do not need vanishing points and measured orthogonals to produce convincing space; you need only relations placed exactly.

The Statue: Human Measure and a Memory of Tradition

Garden statues have long been devices for pacing space and introducing a human axis into vegetal abundance. Matisse uses the motif to do precisely that. The statue—kept deliberately pale and simplified—gives the composition a gentle spine and an echo of classical continuity. It also underscores the painting’s central idea: nature and art are not adversaries here; they cooperate. A human-made form protects a place for looking; living growth provides the plenitude that painting wants to translate.

Flowers as Painted Facts, Not Botanical Studies

The front bed’s blooms are not catalogued species. They are painted facts: pale volumes sitting in green, massed enough to read as a swath of flowering. This choice matters. It puts the emphasis on sensation—how flowering feels in a garden—rather than on illustration—how a specific bloom is identified. Matisse’s brush records the encounter as a rhythm of light and form. The bed becomes the painting’s tactile threshold, the place where the viewer’s own body imagines stepping in.

The Eye’s Route Through the Picture

Matisse composes a path that invites wandering without getting lost. Most eyes begin in the front bed, attracted by the pale flowers against saturated leaves. From there they move along the horizontal of the meadow, then climb the left tree’s calligraphic trunk to the statue. The eye crosses the central foliage—guided by the small accents of cool light—to the house and spire, then slides down the right side’s softer green into the meadow again. The loop can repeat forever because each station on the route offers a distinct pleasure: thick flowers, soft lawn, cool statue, dense trees, distant roofline. The painting thus teaches a calm tempo of looking.

From Fauvism’s Blaze to Nice’s Poise

Seen against the arc of Matisse’s career, “The Garden” shows how the painter refined his early radicality into clarity. The explosive primaries of 1905–1906 have been moderated into a chord of greens punctuated by cool whites. Dissonance gives way to consonance without turning dull. The picture practices restraint—a few forms, a few values, deliberate accents—and that restraint results in authority. In the 1920s Matisse would saturate interiors with pattern; here he learns how to use plant density as pattern while keeping the whole poised and breathable.

Material Particulars That Reward Close Looking

The painting’s body offers pleasures up close. You can see where a stroke of green was pushed into still-wet brown and picked up an earthy fringe, or where a leaf stroke was pulled through a previous layer and left a small valley. In places the canvas tone glows through thinner paint, warming the meadow subtly from underneath. Along the skyline, a dry-brush graze lets gray hang as vapor rather than as solid paint. These material facts matter because they keep the image from becoming a poster. They insist on presence as handwork—decisions made in time, recorded in matter.

The Mood: Contemplative, Sheltering, and Open

Even more than many landscapes, “The Garden” has a mood you can name: contemplative shelter. The dark foliage forms a cradle, the meadow invites pause, the flowers welcome, and the pale house beyond promises human community without insisting upon it. The statue stands like a guardian of calm, neither heroic nor precious, just there to mark proportion and care. This mood is not an accident. It is the product of measured color, democratic light, and the gardener’s clarity of plan.

Dialogues With Other Painters, Answered in Matisse’s Voice

Gardens after 1900 inevitably summon Renoir’s sensual foliage and Monet’s serial explorations of plantings and pools. Matisse acknowledges those elders but speaks differently. He reduces the number of elements, uses black to keep forms articulate, and prizes steadiness over shimmer. Where Impressionist gardens announce the continuous, momentary vibration of light, this garden proposes a longer time scale: the rhythm of tending, the return to a favorite bench, the daily companionship of a statue. It is lyric, but it is not breathless.

Why “The Garden” Still Feels Modern

The canvas feels contemporary because it solves the painting problem with economy. It trusts a few shapes to carry the scene. It lets brushwork be specific enough to convince and abstract enough to generalize. It uses color not to dazzle but to create climate. It respects the viewer’s attention by offering a clear path through complexity. In an age of visual noise, such clarity reads as fresh. The painting does not demand; it steadies.

How to Look Longer and See More

Return to the front bed and let your eyes count the intervals between blossoms; notice how no two leaves are exactly alike in size or orientation, yet the mass reads as one. Track the vertical of the statue and compare its cool whites to the distant house’s grays; they rhyme but do not repeat. Step back and see how the tree mass is not black at all but a weave of greens pushed nearly to the limit of darkness, with curved currents running through it like the grain of a living thing. Watch how the spire pricks the sky with just enough insistence to tilt the whole scene upward. Each of these acts of looking adds to the sense that the garden is both composed and alive.

Legacy and Place Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“The Garden” may appear modest beside Matisse’s monumental decorations or the late cut-outs, but its contribution is substantial. It demonstrates how a painter famous for daring color can achieve profundity with a narrow scale. It proves that black, used with tact, clarifies rather than kills. It shows how a motif as familiar as a flower bed before trees can be renewed when relations are exact. For artists and viewers alike, the painting models a way forward: refine, reduce, and let the work’s tempo carry the feeling.

A Closing Reflection on Care and Continuity

Gardens are acts of care performed over time. So is this painting. Matisse tends to intervals the way a gardener tends to spacing; he balances masses as one balances plantings; he keeps the surface breathing as one keeps soil open. The statue, the house, the trees, and the flowers all claim their place, none bullying the others. In that fairness lies the painting’s grace. “The Garden” is not merely a view; it is a proposal for how to live with things—attentively, proportionately, and with a generous quiet that allows beauty to gather.