Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

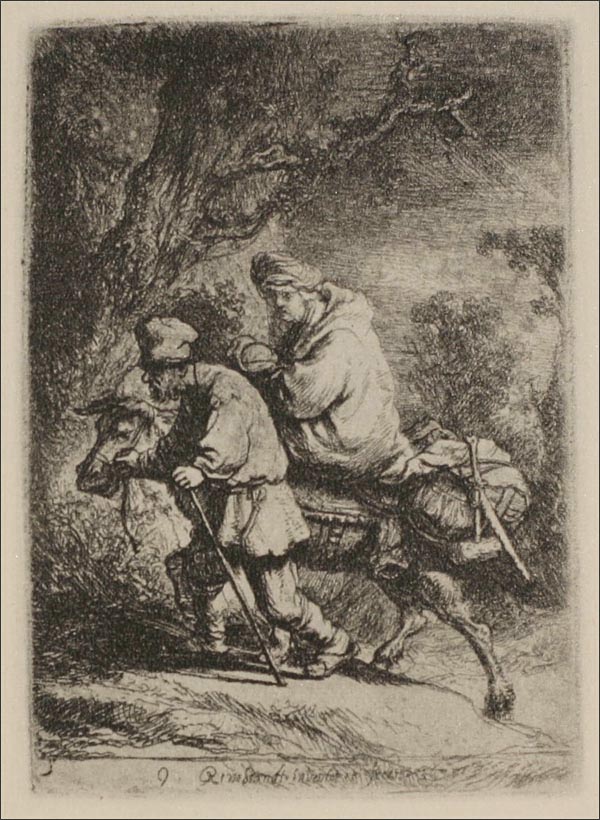

Rembrandt’s “The Flight into Egypt” (1630) is a small etching that unfolds like a night journey. Joseph trudges forward at the head of a humble donkey, staff angled to test the rough path, while Mary rides side-saddle behind him, wrapped against the cold, the bundled infant hidden within the folds of her cloak. Above and around them, gnarled trees and thick shrub become a shadowed tunnel. The light is scant and practical, falling across the ground enough to keep the travelers moving. With a few square inches of copper and a language of hatching and reserve, Rembrandt converts a well-known biblical episode into an intimate study of labor, protection, and steady courage.

The Biblical Narrative Reimagined

The Gospel of Matthew recounts the angel’s warning to Joseph: flee to Egypt with Mary and the newborn Jesus, for Herod seeks the child’s life. Artists had long favored dramatic versions of this escape—moonlit vistas, attendant angels, caravan retinues, or pauses to rest in idyllic groves. Rembrandt strips away embellishment. His Holy Family is not a pageant but a family in motion, poor and purposeful. The donkey bears not only mother and child but the weight of a household bundled on its back. Joseph’s step is determined rather than theatrical; Mary’s posture is practical; the infant’s presence is an idea felt more than seen. By bringing the sacred story down to the scale of ordinary endurance, Rembrandt makes the episode emotionally available to anyone who has walked at night, carried a load, or guarded a sleeping child from unseen danger.

Composition That Walks

The etching is built to travel. A strong diagonal runs from the lower left, where Joseph plants his staff, through the donkey’s angled foreleg, and up along the line of Mary’s back toward the upper right. This diagonal sets the direction of movement and carries the eye through the thicket of hatching that forms the undergrowth. The composition is compressed: figures and animal fill the foreground band, while dense foliage closes in above like a vaulted canopy. The road opens just enough to suggest forward space; the near edge of the image feels like the earth we stand on. Everything pushes onward—staff, hooves, gaze—and the viewer becomes a companion walking beside them.

Etching as Tactile Narrative

Etching preserves the pace of the artist’s hand, and Rembrandt uses this responsiveness to model a world you can almost touch. Joseph’s coat and leggings are knotted together with short, directional strokes that mimic rough cloth and the stiffness of travel. Mary’s enveloping cloak is written with softer, longer lines that report weight and warmth. The donkey’s bristled back is a tangle of quick ticks, while its bony legs are rendered with hard, sparse marks that feel like exposed structure. Rocks, roots, and bark are built from layers of cross-hatching that thicken where darkness gathers. These distinct “dialects” of line keep the small scene legible and lend it the credibility of lived materials.

Light That Serves Purpose

In an etching, light is the gift of restraint—the places where the artist leaves the copper unbitten. Rembrandt uses this gift sparingly to keep the journey believable. Paper white appears along the path, the tilt of Joseph’s face, and the drifts of Mary’s cloak, as if catching stray moonlight or the last coals of an evening sky. Everything else sinks into tonal mid-darkness. The light does not dramatize; it guides. It makes the ground visible and the figures separable without interrupting the privacy of the moment. We are not witnessing spectacle; we are witnessing travel.

The Psychology of Posture

Emotions in this print are communicated by posture rather than facial expression. Joseph leans into his staff with a slight forward bend, the weight of responsibility pulling his torso ahead of his legs. His head tilts downward, not in dejection but in vigilance—he is reading the ground. Mary’s body angles the other way, forming a counter-curve that steadies the composition. She gathers her cloak across her lap, a protective gesture that contains both mother and infant while balancing on the animal’s spine. The donkey steps carefully, ears back, as if listening for command at each stride. Together the three create a grammar of care: provision, protection, and obedient strength.

The Silent Presence of the Child

The infant Jesus is not shown in exposed detail; instead he exists as a tender fullness within Mary’s drapery. This decision accomplishes two things. It centers the mother’s role as shelter and keeps the image focused on the common experience of transporting a sleeping child through uncertain terrain. The sacred is made tangible without overt emphasis. The viewer’s imagination is invited to inhabit the mantle, to feel the small weight and the warmth that justifies the mother’s posture. Rembrandt thereby deepens empathy rather than spectacle.

Landscape as Companion and Obstacle

The surrounding landscape is not a scenic backdrop; it is an active partner in the narrative. Trees loom, their trunks flaring out of the lower corners like sentinels; branches tangle overhead, closing the sky. The undergrowth clumps into dark mounds that narrow the path. Rembrandt’s hatching curves with the terrain so the eye feels the drag of earth along the donkey’s hooves. This environment is both shelter and challenge: it hides the travelers from pursuit and makes every step a test. The result is an emotional weather that matches the story—protective darkness, uncertain footing, and the stubborn light of purpose.

The Edge of Danger Without Illustration

Although Matthew’s account includes the threat of Herod’s violence, Rembrandt refuses to italicize danger. No soldiers appear, no distant fires, no dramatic pursuit. The menace is instead atmospheric: the cramped path, the darkening trees, the averted gazes. This restraint honors the way fear operates during real flight—less a visible adversary than a pressure that advises haste and silence. The family’s security depends on steady motion and quiet resourcefulness, not on miraculous rescue staged for a spectator.

Movement Through Time

The etching reads like a sentence in which each word is a step. Joseph’s foot, staff, and the donkey’s foreleg create a repeated rhythm across the lower edge. The background hatching tilts at different angles to signal shifts in terrain, a graphic counterpart to changing ground underfoot. Mary’s cloak gathers and loosens with the donkey’s gait. Even the tree branches curve in the direction of travel, as if wind or habit had taught them to bow to the path. The viewer experiences time as the coordination of these movements, not as a separate narrative device.

Humanism Without Ornament

Rembrandt’s Holy Family is poor. Their garments are patched; their luggage amounts to bundles; their animal is small. Rather than diminish the subject, this poverty grants it grace. The painting argues quietly that holiness travels with the humble, that sanctity is compatible with weariness and dust. The focus on real effort—bodies that ache, hands that steady, hooves that slip—makes the story not only credible but generous. It recognizes the dignity of families who must move under pressure and offers them a mirror.

Dialogue With Other Flight Images

Rembrandt returned to the theme of the Flight into Egypt multiple times in etching and painting, exploring rest stops, night effects, and angelic guidance. This 1630 version stands out for its compactness and ground-level perspective. Instead of the expansive, moon-washed vistas seen in some later works, here the world wraps close. The choice reflects the artist’s broader Leiden preoccupation with intimate scale and human immediacy. It also prefigures his lifelong commitment to showing biblical narratives as lived experiences populated by people who breathe, carry, and decide.

The Edge of the Plate and the Sense of Witness

A fine etched line frames the scene, holding the dark foliage like a window. The figures press close to this edge, especially at the lower right where the donkey steps out of shadow. The framing intensifies the sense that we stand beside the road within arm’s reach. We are not omniscient observers; we are travelers who happen to walk near enough to see, and near enough to keep quiet. The border thus acts both as a picture plane and as a discipline, reminding us to respect the family’s privacy.

Printing Variants and Mood

As with many Rembrandt plates, impressions can differ depending on plate tone and wiping. A veil of residual ink over the sky deepens the nocturnal mood and pushes the figures forward with greater urgency. A cleaner wipe opens the path and clarifies separate forms, decreasing anxiety and increasing the scene’s calm resolve. These technical variations behave like weather—clouded or clear—without changing the fundamental narrative of steady motion. The plate accommodates both readings, and collectors historically valued this range as part of Rembrandt’s expressive control.

Infancy, Exile, and the Ethics of Care

At the heart of the image lies a moral that needs no inscription: adults form a moving shelter around the vulnerable. Joseph’s body is a windbreak; Mary’s mantle is a house; the donkey is a living floor. The episode becomes a meditation on how families carry their futures when threatened, how they embody hope by the very act of moving it from one place to another. In refusing to theatricalize danger or sanctify the travelers out of recognition, Rembrandt dignifies the ethics of care itself.

The Sound of the Print

The etching is mute, yet it seems to carry sound: the soft clop of hooves on soil, the creak of a saddle, the occasional jostle of bundles, the faint hiss of wind in leaves. Rembrandt suggests this auditory world through rhythm and density—thicker hatching where branches rub, broken lines where undergrowth catches, white reserves where the road smooths out. The sense of sound slows the viewer’s reading of the image to the tempo of walking and makes the print an experience rather than an illustration.

Theological Modesty

While grounded in Christian scripture, the image spreads its meaning gently. Divine protection is present as a mood rather than as a spectacle; providence feels like a path discovered in darkness rather than a burst of celestial light. The holy lies in the faithfulness of the walk itself. This theological modesty aligns with Rembrandt’s larger project: to locate the sacred inside human behavior—gazes, gestures, burdens—and to let light, even the faint light of a winter road, perform the role art once reserved for halos.

Lessons for Draftsmen and Storytellers

The plate offers a compact tutorial in narrative drawing. Build motion with diagonals and repeated steps. Assign different kinds of line to different materials so that even in small scale each element reads at a glance. Let light be useful; reserve paper where the eye must find ground or faces. Use the frame to control the viewer’s role. Keep danger as pressure rather than spectacle when the story calls for sustained human effort. Above all, show emotion through posture. Mary’s sheltering curve, Joseph’s forward lean, the donkey’s measured step—these do more than any theatrical grimace could.

A Scene That Travels Across Centuries

The continued appeal of “The Flight into Egypt” rests in its clarity about ordinary heroism. In any century, families flee war, poverty, or persecution; adults cradle children against cold; paths are chosen in fear and hope. Rembrandt’s etching refuses both sentimentality and cynicism. It acknowledges hardship and honors the dignity of response: walk, carry, watch, keep going. Viewers recognize themselves in this ethic, whether or not they share the biblical story’s creed.

Conclusion

In “The Flight into Egypt” of 1630, Rembrandt turns a familiar narrative into a close, unadorned journey. Joseph advances into rough country, Mary gathers the infant within the shelter of her cloak, and a small, sturdy donkey bears them forward. Trees and shadow encircle the path, and light falls where it is most needed. The print’s power lies in the care with which it treats motion, material, and posture. It transforms fear into vigilance, poverty into resourcefulness, and faith into the steady fact of travel. The scene moves past us and keeps moving; we remain on the verge of the road, listening to the quiet cadence of hooves and steps, and we understand that this is how salvation often looks: ordinary bodies carrying each other toward safety through the darkness.