Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

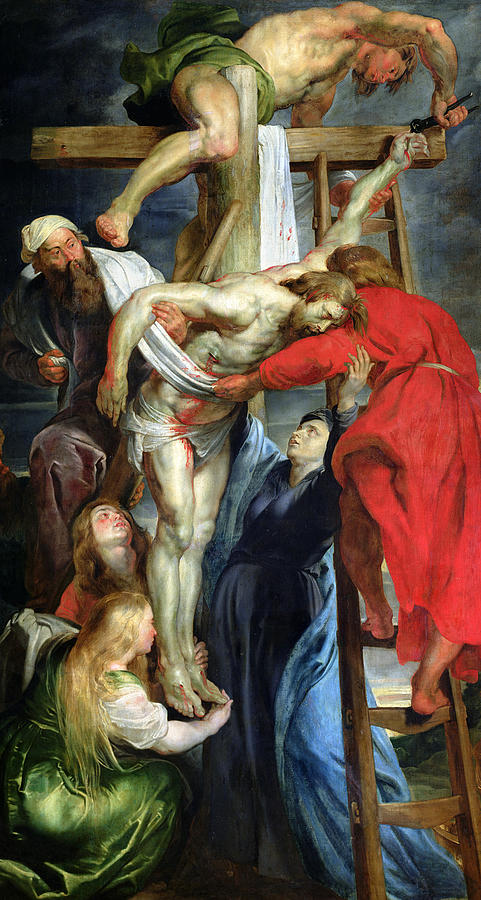

“The Descent from the Cross” by Peter Paul Rubens is one of the most moving visual meditations on the Passion ever created. In this towering composition the lifeless body of Christ is being carefully lowered from the cross by friends and followers, surrounded by the grief-stricken Virgin Mary and the holy women. Rubens turns this transitional moment—between Crucifixion and Entombment—into a vortex of emotion and physical strain. Muscular bodies twist on ladders, fabric stretches under the weight of the corpse, and faces register shock, tenderness, and despair.

The painting reveals Rubens at the height of his Baroque powers. He combines monumental figure design with intricate choreography, using diagonal movements, rich color, and dynamic light to immerse the viewer in the scene. At the same time, the work fulfills a devotional purpose: it invites contemplation of Christ’s sacrifice and the compassionate participation of those who loved him.

Biblical Narrative and Devotional Context

The subject comes from the Gospel accounts describing how Joseph of Arimathea, Nicodemus, and several disciples took Jesus down from the cross after his death. They wrapped his body in a shroud and laid him in a new tomb. Christian art quickly developed a distinct iconographic stage known as the “Descent from the Cross,” emphasizing the physical act of removing the body and the emotional reactions of the witnesses.

In Catholic Europe this theme became especially important during the Counter-Reformation, when artists were encouraged to create images that stirred empathy and reinforced belief in Christ’s real, bodily suffering. Rubens, who painted more than one version of the Descent, crafted this composition as an intense devotional focus. Viewers are not distant observers; they are drawn close to the cross, almost able to touch Christ’s bloodied feet as they slide toward the foreground.

Vertical Composition and Diagonal Movement

The first striking feature of the painting is its vertical format. The cross occupies the top half, while the figures at its base cluster into the lower portion. This tall format emphasizes the height from which Christ is being lowered, making the act of descent feel physically dangerous and emotionally momentous.

Rubens organizes the figures along strong diagonals. Christ’s body forms a sweeping diagonal from the upper left to the lower right, echoed by the direction of the ladder and the lines of the shroud that supports him. Other diagonals run counter to this: the man in green and brown high on the cross leans from right to left, while St John in vivid red pulls the body downward in the opposite direction. These intersecting lines create a sense of movement and tension, as if the composition is momentarily caught between the vertical of the cross and the inevitability of Christ’s fall into the arms of his followers.

The diagonals also have a symbolic dimension. The downward slant of Christ’s body suggests his descent into death and the grave, but it also anticipates the descent into human misery that Christian theology interprets as an act of saving love.

The Body of Christ

At the center hangs the pale, muscular body of Christ, already marked by death. Rubens paints the flesh with extraordinary sensitivity: it is heavy, slack, and cool, yet still beautiful. The slightly twisted torso reveals both the brutality of crucifixion and the dignity of the martyr. Blood trickles from the wounds in his side, hands, and feet, but the overall effect is not gruesome; instead, it is poignant and solemn.

Christ’s head droops onto his chest, crowned with thorns. His eyes are closed, his mouth slightly open. The pose recalls classical depictions of fallen heroes, but Rubens intensifies the emotional implications by placing Christ’s body in contact with so many grieving hands. It is a body that has been loved and is now being cared for with infinite tenderness.

The white shroud that helps support him functions both practically and symbolically. Practically, it is being used as a sling to lower the body. Symbolically, its pure whiteness contrasts with the reds and deep blues around it, suggesting innocence, sacrificial purity, and the burial cloth that will soon wrap Christ in the tomb.

The Men Lowering Christ

At the top of the cross a man in a green loincloth, commonly identified as one of the helpers, clings to the wood while reaching down with both arms to control the shroud. His body is taut with strain; muscles bulge as he balances precariously. Rubens captures the dangerous acrobatics required to carry out this sacred task.

Below him, on a ladder to the right, stands another man clothed in vivid red—often interpreted as St John the Evangelist. He lifts Christ under the shoulders, pressing his cheek close to the limp head. The intimacy of this contact reveals John’s deep love and grief. Despite the weight, his expression is more sorrowful than strained.

On the left, Joseph of Arimathea or Nicodemus supports Christ’s legs, his face partially turned away in solemn concentration. His older, bearded features and sturdy stance contrast with John’s youthful sadness. Together these men form a living support structure, replacing the nails and wood with human arms and devotion.

The Women at the Foot of the Cross

At the base of the composition gather the women whose emotions reflect the response of the faithful viewer. The Virgin Mary, in deep blue, stands directly under her son’s body. She reaches up with both arms, as if to receive him, her face raised in a mixture of anguish and worship. Unlike more passive depictions of Mary, Rubens shows her actively participating in the descent, emphasizing her role as co-sufferer and model of steadfast faith.

To the left kneels Mary Magdalene, recognizable by her long golden hair and expressive features. She clutches Christ’s feet, pressing them to her cheek. Her posture combines adoration and desperate grief. The bright highlights on her hair and garment draw attention to this gesture of penitential love.

Another woman, possibly Mary of Clopas, supports the Virgin from behind or beside, her face contorted with emotion. These women create a visual echo of the men above: where the male figures labor physically, the female figures bear the emotional weight, channeling sorrow on behalf of the viewer.

Light, Color, and Dramatic Atmosphere

Rubens uses light in a highly theatrical way. The overall background is relatively dark: stormy sky, shadowed cross, and muted rock or architecture. Against this gloom, Christ’s pale body glows with an almost supernatural luminance. This contrast heightens the sense of him as the light of the world, even in death.

Color plays a significant symbolic role. The strong red of John’s robe and of the shroud stained with blood speaks of love, sacrifice, and the Eucharistic connection to Christ’s blood. Mary’s deep blue robe suggests fidelity and heaven. The greens and earth tones of the other figures connect them to human frailty and the natural world. Together these hues form a rich palette characteristic of Rubens, where color is both decorative and theological.

Subtle highlights on the ladder, the nails being removed, and the folds of cloth create a sense of three-dimensional reality. The viewer can almost feel the roughness of the wood and the softness of the fabric, making the scene more immediate and tangible.

Baroque Emotion and Physicality

“The Descent from the Cross” is quintessentially Baroque in its emotional intensity and physical dynamism. Rubens does not shy away from showing bodies in strenuous action. The figures twist and turn in complex poses, yet their movements are fluid and natural. Hands clutch, reach, and support; faces reveal a spectrum of feelings from stoic concentration to open weeping.

This emphasis on physicality serves spiritual purposes. By foregrounding the effort required to lower Christ, Rubens underscores the reality of his death. This is no ghostly apparition; it is a heavy, human body that must be handled with care. At the same time, the vigorous gestures convey the fervent love of those who serve him. In Baroque art, bodily expression is a path to inner truth, and Rubens uses it masterfully here.

Theological Symbolism

Beyond its narrative content, the painting is rich in symbolic meaning. The downward movement of Christ prefigures his burial but also hints at the doctrine of the descent into hell, where he is believed to liberate the righteous dead. The strong diagonals leading downward may also evoke the outpouring of grace from the cross into the world.

The coordinated actions of the group suggest the Church itself—men and women of different ages and characters united around the body of Christ. Each has a role: supporting, grieving, preparing. This communal aspect reflects the idea that salvation history is not only about Christ’s solitary sacrifice but also about the community that gathers around it in faith.

The ladder, cross, and nails remain visible, reminding viewers that the wounds and instruments of torture are part of the story even as the event moves toward burial and eventual resurrection.

Altarpiece and Devotional Experience

Although the image here is seen in isolation, Rubens originally conceived this composition as part of a larger altarpiece complex. In its original setting, the central panel would have been flanked by related scenes and situated above a real altar where the Eucharist was celebrated. The downward slant of Christ’s body could visually direct the viewer’s attention from the painted sacrifice to the sacramental one enacted below.

For worshipers, standing before this image during Mass or personal prayer, the painting would function as a bridge between past and present. The visceral depiction of Christ’s dead body made the Passion feel immediate, while the expressions of Mary, John, and the Magdalene provided emotional templates for devotion—sorrow, gratitude, and love.

Rubens’ Artistic Synthesis

Rubens had studied Italian Renaissance masters, including Caravaggio, Michelangelo, and Titian, and elements of their influence appear in this work: the muscular anatomy, the dramatic lighting, the rich color. Yet he synthesizes these sources into a personal style marked by fluid brushwork, emotional warmth, and intricate composition.

In “The Descent from the Cross,” he successfully balances narrative clarity with expressive complexity. Every figure is legible and purposeful, yet the overall scene feels spontaneous and deeply human. The painting stands as a testament to Rubens’ ability to fuse theological depth with artistic virtuosity.

Conclusion

Peter Paul Rubens’ “The Descent from the Cross” is far more than a representation of a biblical event. It is a carefully orchestrated drama of grief, devotion, and hope, designed to move the heart as well as the eye. Through a towering vertical composition, powerful diagonals, luminous color, and intimately rendered faces, Rubens captures the moment when Christ’s lifeless body passes from the instrument of torture into the arms of those who love him.

The painting invites viewers to join that circle: to feel the physical weight of the body, to share the Virgin’s sorrow and the Magdalene’s devotion, and to recognize in the straining muscles and tender gestures the depth of human response to divine sacrifice. As a masterpiece of Baroque religious art, “The Descent from the Cross” continues to speak across centuries, reminding us that faith is not abstract but embodied, and that the story of redemption is written in both blood and tears.