Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

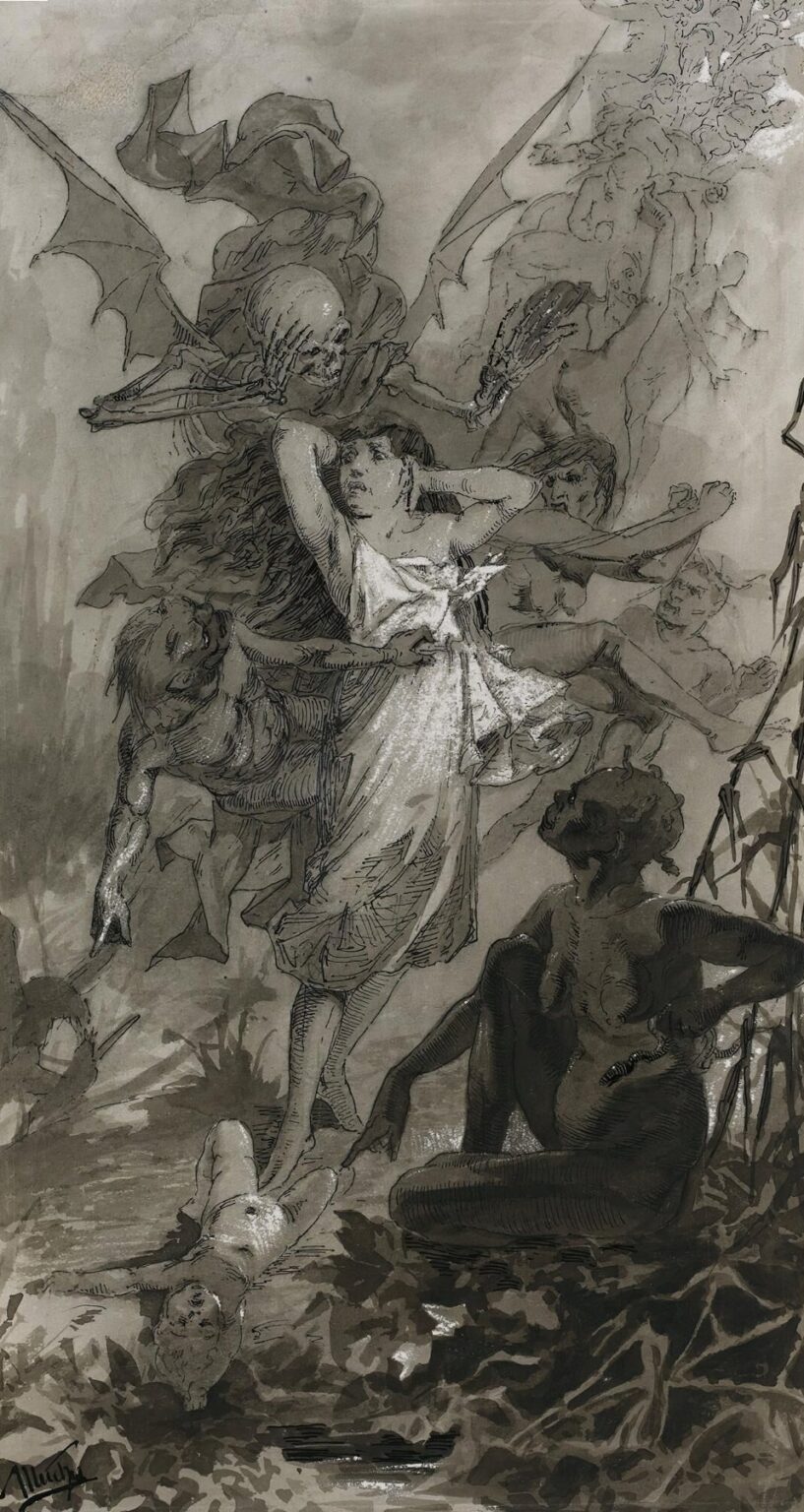

Alphonse Mucha is usually associated with radiantly colored posters, sinuous borders, and triumphant heroines crowned with flowers. “The Dance Of Death” overturns those expectations. In this vertical drawing, executed in ink and wash with white heightening, a bat-winged skeleton hauls a young woman upward while a swarm of grotesques clutch and taunt her. Below, a dark figure crouches among reeds, and at the very bottom a small, limp child lies splayed on the ground. The scene is a maelstrom of grasping hands, torn drapery, and smoky atmosphere. Rather than advertising a theatre or perfume, the sheet advertises nothing except the stark fact of mortality. It is Mucha at his most symbolist and existential, proving that the elegance of his line could carry terror as convincingly as beauty.

The Subject and Its Lineage

The title places the work within the centuries-old danse macabre tradition. From medieval murals to nineteenth-century prints, artists have personified death as an animated skeleton who intrudes upon daily life to lead people of every rank in a final procession. Mucha modernizes this tradition by shifting from procession to abduction. Death here is not a courtly partner but a winged predator that seizes its victim mid-gesture. The dance is still present, however, not as a polite step but as a vortex of bodies spiraling through space. The woman’s twisting torso, the grasping imps, the upward pull of the bony arms—everything moves to a rhythm that is both choreographic and chilling.

Composition and the Logic of Movement

The design is organized around a powerful diagonal that sweeps from the upper left, where Death’s wings launch into the air, down through the woman’s arched body to the prone child at lower left. A counter-diagonal rises from the crouching demon at the lower right to the crowd of sketchy figures at upper right. These intersecting flows create a whirlpool that keeps the viewer’s eye circling the page. Mucha also uses three distinct figure scales to structure depth: the monumental central pair, the mid-scale demons at either side, and the small, ghostly assembly fading into the smoke at the top. The proportions are theatrical, but the logic is clear. We are meant to feel pulled upward with the victim, dragged sideways by the demons, and then cast down toward the child, who anchors the drama in a single heartbreaking detail.

Technique: Pen, Wash, and White Heightening

Unlike the flat color of Mucha’s lithographs, this sheet is painted in grisaille. A warm gray ground wash sets the tonal stage. Over it, the artist draws with a dark pen line that defines bone, muscle, and fabric. He then modulates forms with transparent ink washes—pale veils around the floating spirits, denser pools in the marsh and wings. Finally he strikes the brightest planes, such as the woman’s dress and Death’s glinting skull, with touches of opaque white. The combination produces remarkable plasticity. The white is not decorative sparkle; it is structural light that carves volumes out of smoke. Hatching reinforces the direction of movement, with slashed strokes across drapery and concentric marks around the skull to suggest vibration, as though the very air hums with menace.

Light and Atmosphere

The sheet reads like a night scene lit by a lurid, offstage source. Brightness flares on the woman’s dress and on the child’s tiny torso, as if a pit of fire or a flash of lightning has raked the ground. This directional light throws the demons into relief and sets their bodies against the surrounding gloom. In the upper right, light dissolves into vapor; figures are merely suggested by contour, becoming more ghost than flesh. Mucha is masterful here at staging visibility. He makes us squint into the murk and then confronts us with sharp clarity where it hurts most—the human faces and small hands.

Death Personified

Mucha’s Death is not a static emblem but a creature. The skull tilts forward in a predatory sniff; the spinal column bends; membranous wings beat backward with batlike anatomy; ragged shrouds billow as if alive. The bony fingers, long and articulated, clamp the woman’s shoulder and wrist. There is nothing comic or ornamental in this skeleton. It is a constructed body that obeys a grim physics. Yet it is also strangely courtly in gesture, echoing the old dance prints. The right arm wraps around the woman in an embrace that could almost be a waltz hold—until one notices the talons and the terror in the eyes of the partner.

The Woman as Figure of Humanity

The woman’s body is the emotional center. She turns in a classic spiral—hips one way, shoulders the other—creating the beautiful, vulnerable contrapposto that Mucha often gave his poster heroines. Here, however, the twist is a recoil. One hand shields the ear, as if the howling of demons were unbearable; the other struggles against Death’s grip. Her dress, rendered with white heightening, is the brightest thing in the image, a fragile banner of life and light amid the surrounding gray. The bow at her waist, tender and domestic, intensifies the pathos. Mucha avoids melodrama in the face; the mouth is open but not screaming. She seems to be in the instant of realizing that struggle is futile—a moment more devastating than panic.

Demons, Imps, and the Theatre of Cruelty

At the lower right crouches a dark, horned figure who points toward the child with a gesture of both accusation and delight. Another twisted goblin clings to the woman’s hip, one hand reaching down toward the small body on the ground. At the upper right, sketchier figures tumble and flail, their limbs melting into smoke. These creatures are not catalogued monsters; they look improvised, as though the artist allowed ink washes to suggest forms that he then sharpened with line. The method suits the subject. Evil seems to condense out of the air, taking whatever shape malice requires. The pointed fingers and sly mouths recall caricature, yet the tonal setting keeps them anchored in dread rather than humor.

The Child as Irrefutable Fact

Few details strike as hard as the small figure lying at the bottom. The child’s head is thrown back, the arms flung wide, the belly highlighted by white. This is not an allegory in the abstract; it is a world in which even the most innocent body is subject to the dance. Mucha resists gruesome specificity—there is no blood, no wound—but the position leaves little doubt about the outcome. The dark patch of ground beneath the child functions like a period at the end of a sentence, the grammatical full stop of mortality.

Setting and the Geography of Fear

The immediate foreground is a tangle of reeds and muck, suggested with broad brush and ink splatter. It feels like a swamp or riverbank—liminal terrain where life rots into new life. The choice is apt: the danse macabre traditionally unfolds in the presence of cemeteries or churchyards, places where the living and dead share soil. Mucha’s marsh is secular but similarly in-between. Above, the air itself becomes habitat. Spirits form and unform within a weather system of smoke. The environment is not there to be admired; it participates in the assault, providing cover, depth, and path for the action.

Line, Ornament, and the Subversion of Beauty

One of the sheet’s most unsettling pleasures is how Mucha uses the same seductive calligraphic line that, in his posters, draws jewelry and hair, to describe bone and claw. Drapery swirls with the grace of his advertising panels, yet here those swirls magnify panic rather than luxury. The elegant arabesque becomes a trap. It is a remarkable demonstration of how style carries moral ambiguity. Beauty, the drawing suggests, is not an argument against death; death can dance beautifully too.

Dialogue with Symbolist Culture

The fin-de-siècle nourished a taste for the uncanny—think of Redon’s cyclopean heads, Munch’s spectral figures, or the decadent literature of fear and desire. Mucha is often placed apart from that current because of his commercial success. This sheet insists on his membership. The hybrid of seduction and terror, the eroticized rescue that is also a capture, the dreamlike logic of space all mark Symbolism at full strength. Even the choice of medium—ink wash that allows forms to dissolve—is symbolist in spirit, fitting a theme about the web between body and spirit.

Relation to Mucha’s Broader Oeuvre

Seen beside Gismonda, Monaco Monte-Carlo, or The Seasons, this work is a dark mirror. The feminine figure remains central, the drapery still billows, and the composition retains a halo-like shape around the principal head. But everything has been inverted. The halo is smoke; the flowers become claws; the celebratory uplift becomes forced ascension. The connection is particularly strong with Mucha’s mystical book Le Pater, in which he explored temptation, deliverance, and suffering through monochrome plates. “The Dance Of Death” could sit among those images as the clause that reads, simply, “deliver us from evil”—not as plea but as question.

Draftsmanship and the Evidence of Process

Because the sheet is not a printed poster, we can see the hand at work. Some figures are fully modeled; others are barely blocked in. Ink puddles mark where a wash was pushed and pulled with a wet brush. A few contours are reinforced, suggesting that Mucha revised the pacing of the action after initial lay-in. The white heightening, applied with a small brush, sometimes catches the tooth of the paper and breaks into sparkling grain. The signature sits stark at the lower left, anchoring authorship to a scene where everything else slides toward anonymity. These traces of making intensify the experience. We feel the image as both story and event in the studio.

The Emotional Register

The sheet does not trade in shock for its own sake. Its emotion is dread, a slower, deeper sensation than terror. The woman’s posture communicates it; the demons’ calm pointing communicates it; even Death’s expressionless skull communicates it by its lack of change. The horror is not that death arrives; it is that it arrives with such patience, such inevitability, such composure. This mood is reinforced by the monochrome palette. Without bright color to excite, the viewer must sit with the grays, where dread thrives.

Interpreting the Allegory

What message, if any, does Mucha intend beyond the memento mori? The woman’s white dress and bow suggest everyday life—marriage, home, ordinary joy—interrupted. The demons’ gestures toward the child point to the cruelty of fate that spares neither age nor innocence. The upward swirl of bodies at the right might be souls swept into the same current, implying that the dance binds all. At another level the image can be read as a meditation on desire and danger. The abduction has erotic undertones; the grasp around the waist, the lifted thigh, the clinging imp at the hip recall images of seduction that the period loved to complicate. Mucha may be warning how life’s most beautiful dances—love, ambition, pleasure—can pivot into harm with a step.

Pacing the Viewer’s Gaze

Mucha composes the image so that the eye moves in a loop, never quite finding a safe resting place. We begin at the pale dress, shoot up to the skull, glide along the wings, swerve into the ghostly crowd, slide down the reed bank to the crouching demon, and then, almost against our will, confront the tiny body at the bottom. From there the bow at the woman’s waist pulls us back upward. This circulation is the dance promised by the title. The viewer participates, learning the choreography of loss step by step.

The Work’s Place in the Modern Imagination

In an age saturated with images of catastrophe, Mucha’s sheet still grips. Part of its power lies in the balance of specificity and myth. The anatomy, gestures, and light feel convincingly observed even as the situation is impossible. The child is not a symbol; it is a child. At the same time, the absence of a particular setting or story lets viewers supply their own associations—war, disease, personal grief, the universal fact of time. The drawing becomes a vessel for memory.

Lessons for Design and Illustration

For artists and designers, “The Dance Of Death” offers a compact tutorial. It shows how a limited palette can produce vast emotional range; how diagonals and counter-diagonals build dynamic stability; how white heightening can model form and guide attention; how contour and wash, when interwoven, create depth without clutter. Most importantly, it demonstrates how a consistent line language can operate across radically different moods—selling champagne in one work, facing the abyss in another—without losing integrity.

Conclusion

“The Dance Of Death” proves that Alphonse Mucha’s art is larger than the poster style that made him a household name. His calligraphic line, mastery of drapery, and instinct for theatrical composition here serve a subject as old as art itself. Death does not invite a polite minuet; it seizes, spirals, and points. The woman resists and recognizes. Demons delight. A child lies still. Out of ink, wash, and a few strokes of white, Mucha shapes a dance that viewers continue to learn, unwilling partners all. The sheet is bleak, yes, but it is also intensely alive with looking—alive in the precision of hands, the curl of fabric, the persuasive weight of bone. In facing what ends us, the artist reaffirms what art can do: hold a moment so completely that we cannot turn away.