Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

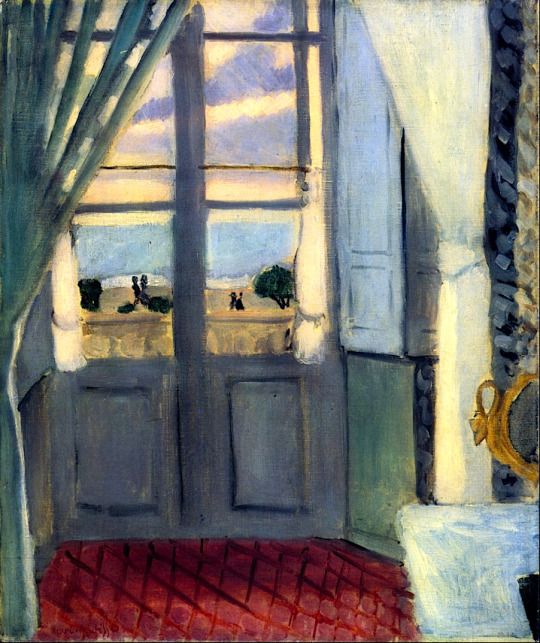

Henri Matisse’s “The Closed Window” (1919) is a quiet masterwork about thresholds, privacy, and the architecture of looking. A pair of French doors fills the center of the canvas, their panes turning the world beyond into a measured grid of sky, promenade, and sea. Pale blue-gray woodwork steadies the view; gauzy curtains pool into soft knots at the crossbars; a cool wash of afternoon light slips across the room. Inside, a red lattice floor, a drawn curtain at left, a sliver of green wainscoting, and the flash of a small gilt mirror on the right become the painting’s chorus. Nothing dramatic happens, yet the picture hums with anticipation. The closed window keeps us within, but it does not shut the world out; it frames the world so that color, light, and time can be felt with uncommon clarity.

Historical Context

Painted the first year after the Armistice, the work belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period, a phase when he rebuilt pictorial harmony by returning to rooms, balconies, and calm light. Europe had emerged from war bruised and uncertain. Instead of spectacles or manifestos, Matisse offered interiors where the eye could rest and the mind could knit itself back together. In Nice he found a climate that softened shadows and let color settle into long, even chords. The window motif became central: sometimes flung open onto sea and sun, sometimes filtered through shutters, sometimes, as here, closed—an image of being turned inward while staying in conversation with the world.

Composition and Framing

The composition is built around the tall rectangle of the window, placed slightly off-center to the left so that the right side of the room—a wall with a pebbled strip and the flash of a round mirror—can counterweight it. The doors divide into four large panes; across the lower third a stone balustrade runs horizontally, compressing the exterior. The tiled floor in the foreground tilts upward in a red lattice that guides the eye toward the threshold. A curtain drifts in from the upper left, its folds diagonal and soft, while on the right a pale shutter sits flush with the wall, a second vertical that strengthens the architecture. The whole design is a study in measured tensions: verticals of door and shutter, horizontals of balcony and horizon, diagonals of floor and curtain. The room is shallow but breathable, a small theater built to stage light.

The Window as Subject

Matisse does not treat the window merely as a device for a view; he makes it the picture’s protagonist. Closed, it becomes a membrane rather than a passage, a plane that records weather and time. The panes register lavender clouds and a band of sky; they collect the cool of sea and the earth tone of the promenade. The mullions and rails turn those sensations into an ordered grid so that color can be compared and savored. A closed window also changes the viewer’s relationship to what is seen: we do not rush out; we contemplate. The world becomes an image, and painting acknowledges its kinship with glass.

Color Architecture

Color builds the room’s temperature. The doors are a cool, chalky blue that calms and clarifies the center. The red lattice floor is a warm counterchord, pushing energy up from below. The walls hover in pearly whites and pale greens, creating a climate in which both warm and cool can breathe. Through the panes the sea reads as a tempered blue, the promenade as ochre, the trees as deep green commas, and the sky as bands of violet and cream. These exterior notes are restrained, as if filtered by the glass, and they settle into the interior harmony without insisting on contrast. A small flash of gilt at the far right—the mirror’s frame—adds a single bright metallic accent that catches the room’s light and returns it.

Light and Atmosphere

The painting is saturated with a gentle, marine light. It falls across the floor in a thin, rosier tint, washes the doors in a matte glow, and bleaches the curtains where they knot on the crossbar. There are few hard shadows. Instead, soft zones of illumination turn forms and register distance. Outside, the horizon is clear but not harsh; clouds streak sideways in violet bands, as if the day were drifting rather than advancing. The interior retains its own weather: we feel the cool of painted wood and the warmth of tile, the hush that closed windows make in seaside towns when the light is strong but the air is thin.

Pattern and Rhythm

Pattern is subdued but decisive. The most assertive rhythm belongs to the floor: red lines cross at diagonals, each intersection slightly irregular, so that the grid feels handmade rather than mechanical. That lattice echoes the window’s muntins and rails, a quiet rhyme between ground and view. The curtain’s folds add a second rhythm—slow, vertical waves that soften the scene’s geometry. Along the right margin, a strip of pebble-like pattern reinforces the wall’s edge and keeps the eye from slipping out of the picture. Even the balustrade’s stones repeat across the central band, their rounded tops a set of soft beats under the more legible bars of the window frame.

Interior Objects and Their Roles

Matisse includes very few objects: the curtain, the shutter, the mirror’s gilt ring, the marble-like edge of a table in the lower right corner. Each is a structural actor. The curtain declares the left boundary and introduces movement; the shutter reaffirms the right boundary and repeats the window’s planes; the mirror offers a sun-warm accent and a hint of reflection without stealing attention; the table’s white edge is a cool, solid note that grounds the corner. Such economy gives each element weight and honors Matisse’s belief that the painting’s structure should register cleanly in memory.

Space and Perspective

Depth is present but controlled. The lattice floor implies recession without mathematically precise orthogonals; the double doors sit squarely in the wall; the outside world is flattened by the panes and by the horizontal bar of the balustrade. Overlap and value changes cue distance, but the painting refuses deep illusion. That refusal is not a negation of space—it is a modernization of it. The window keeps the exterior at the surface, preventing the painting from becoming a view and keeping it a constructed image. We occupy a measured wedge of room, and beyond the glass another measured wedge of world. The two echo and balance each other.

Time and Weather

“The Closed Window” is saturated with time, though no clock appears. The lavender streaks across the sky suggest early or late light, the hours when color lengthens and the day holds still. Figures on the promenade—tiny, dark notations—move in pairs, like punctuation marks in a long sentence. The closed window transforms those distant motions into gentle signs of duration. We witness time but do not enter it; we allow it to unfurl on the far side of glass while we attend to the near side’s quiet. In a year when many sought rest from history, such an image was a humane proposition.

The Psychology of Inwardness

Because the window is closed, the room turns slightly inward. We are not asked to look at a person; we are asked to inhabit a mood. The curtain’s thick fold and the shutter’s flat plane behave like comforting hands at either side of the opening. The red lattice breathes warmth into the floor; the door’s blue cool steadies it. The small mirror is a private glint—personal, unboastful—reminding us that interiors are places where self is assembled. The painting’s psychology is not melancholy; it is composure. We feel a poised attention that refuses both claustrophobia and overexposure.

Drawing and the Visible Hand

Matisse keeps the drawing frank. Lines around the panels and panes are slightly wobbled, acknowledging the pressure of a hand rather than the certainty of a drafting tool. The curtain’s edges soften into the air; the shutter’s seams are stated with a few dark strokes; the texture of the pebble-strip at right is achieved with quick ovals and smears. The outside figures are dots and commas—minimal marks that keep the world at a proper scale. Nothing is belabored, and because nothing is belabored, everything feels present.

Material Presence and Surface

The paint sits in varied layers that contribute to the room’s tactility. Thin scumbles on the wall allow the canvas weave to breathe; thicker, matte passes on the door panels make the wood read as weighty; the floor’s reds are dragged to catch in the tooth of the ground, replicating the chalky reflectiveness of tiles. Highlights are sparing but telling: a glint on the mirror’s frame, a pale note at the curtain’s knot, a soft bloom where light pools on the bottom rail. These material differences convince more deeply than literal textures would, because they are true to paint’s nature.

Comparisons within the Nice Period

Seen beside Matisse’s open-window canvases of 1918–1921, this painting reads as a counterweight. Where “Woman with a Red Umbrella” or “Girl with Pink Umbrella” fling open doors to sea light and stripes, “The Closed Window” narrows the aperture and lets the room absorb the day. The red lattice floor here is cousin to the brighter grids of other interiors; the pale shutters and blue doors echo the coastal architecture repeated throughout the period. Yet the mood is more contemplative. The closed pane suspends exuberance and invites a deeper listening to color’s quieter harmonies.

Dialogue with Tradition

Window pictures reach back from Dutch genre interiors to the nineteenth-century French fascination with balconied rooms. Matisse inherits that lineage and simplifies it. He refuses deep perspective and minute description in favor of a surface where color and shape conduct the drama. The balustrade and the promenade below evoke the Mediterranean seaside hotels beloved by travelers and painters alike, but they appear as modules inside a modern construction. The painting thus honors tradition while committing to contemporary clarity.

How to Look

The image rewards a slow, deliberate route. Let the eye begin at the floor’s nearest diamonds and follow the grid toward the center rail; climb the vertical of the left door to the lavender clouds, then step across the panes to the sea’s horizontal band; glance at the distant walkers; return down the right muntin and notice the shutter’s pale plane; slip to the gilt flash of the mirror; and finally rest on the cool white edge of table or sill. Each pass tightens the sense that interior and exterior echo each other—diamonds and panes, warm and cool, private glint and public horizon. The looking becomes the picture’s subject.

The Ethics of Restraint

Perhaps the most radical quality of “The Closed Window” is its restraint. Matisse resists the temptations of scenic detail, virtuoso reflections, or sentimental narrative. He builds a place that holds steady because its elements are proportioned to one another with care. In doing so he proposes a way of living with the world after upheaval: attend to relations, keep thresholds clear, value the climate of a room as much as the view beyond it. The painting’s beauty is inseparable from that ethic.

Legacy and Foreshadowing

The clarity of silhouette, the reliance on repeating modules, and the compression of space anticipate the graphic decisiveness of Matisse’s cut-outs decades later. In those paper works, windows become pure rectangles of color and the world beyond resolves into arcs and leaves. “The Closed Window” retains oil’s softness, yet already it treats the view as a designed pattern. It stands as a hinge between painterly interiors and the later language of shape.

Conclusion

“The Closed Window” is a meditation on how to hold the world at a humane distance without losing touch with it. A red lattice floor, a blue-gray door, a soft curtain, a pale shutter, a flash of gold, and a measured view of promenade and sea—these ingredients, ordered with grace, create an image of composure that still feels urgent. Matisse shows that color can build architecture, that pattern can steady time, and that a room can be both sanctuary and observatory. Standing before this canvas, we breathe the room’s tempered light and feel the day beyond it traveling at a kindly pace.