Image source: wikiart.org

A Working Room Where Painting Learns To Breathe

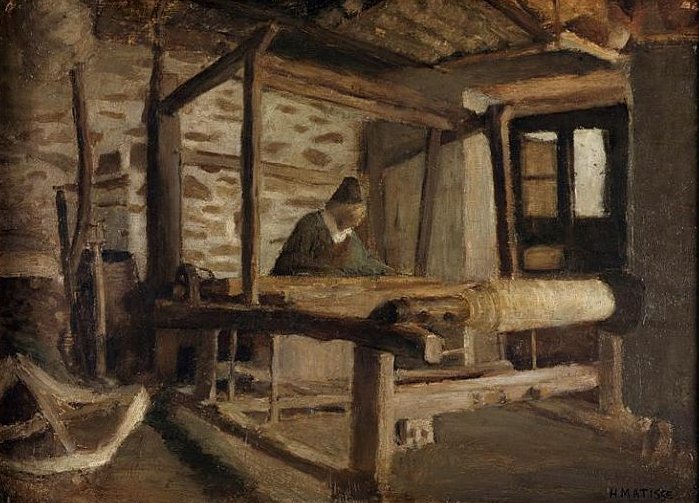

Henri Matisse’s “The Breton Weaver” of 1895 is an interior so spare and brown that viewers who know the artist for his blazing reds and swimming-pool blues sometimes blink in disbelief. A single figure bends over a loom inside a stone-walled room, the wooden frame of the machine rising like a small architecture within a larger one. Light filters in from a doorway and a window, breaking across beams and posts before dying into shadow. Nothing announces itself as dramatic, yet the painting smolders with attention. It is a portrait of labor and, just as crucially, of a young painter learning how to make space, light, and structure carry meaning before color takes the stage in his later work.

Historical Moment And The Road To Brittany

By 1895 Matisse was still in his twenties and committed to rigorous training. He copied old masters, studied value and drawing, and painted sober still lifes and interiors that display a craftsman’s patience. Travel to Brittany—then a magnet for artists seeking preindustrial customs and unspoiled landscapes—put him in contact with a rural culture that still preserved handcrafts and traditional dress. “The Breton Weaver” belongs to this moment of observation. Long before Matisse covered his canvases with textiles in Nice, he studied the original conditions of weaving as labor, noise, and wood and cloth under the pressure of hands. The painting is, in one sense, Matisse’s apprenticeship to the architecture of making.

What We Look At When We Enter The Room

The loom dominates the foreground: four uprights carry the weight of a horizontal beam; a stretched roll of cloth or warp sits at right; crossbars run like rafters; a plank bench and pedals hint at the machine’s choreography. Behind the loom, a figure in a dark cap leans forward, sleeves swallowing the forearms, head bowed to the task. The stone wall at the back records irregular light patches; to the right, a half-open door and window admit a cold day’s pallor. The lower register of the painting is the world of work—wood, floor, legs, levers—while the upper register is air and stone, a space that holds the clatter and the focus. Matisse positions us slightly off-center, so the massive beam of the loom slides diagonally toward us, letting the eye travel under and through the machine as if it were a forest of timbers.

The Loom As Architecture And Metaphor

Few paintings of interiors treat a tool with such structural gravity. The loom’s posts are columns, its crosspieces lintels, its pedals and rollers a mechanical nave. It domesticates architecture inside architecture. That doubling has a metaphorical bite: weaving constructs fabric the way a builder constructs a house, and Matisse composes a painting in the same constructive spirit. The image becomes a quiet manifesto for making as a primary human act. In later decades Matisse would surround his models with patterned cloths and cut paper into woven rhythms; here the pattern is not decorative but latent, a potential the loom will unlock.

The Geometry That Holds The Silence

The painting rests on a set of measured rectangles and slanted planes. The door’s dark rectangle counters the pale trapezoid of the window. The loom’s horizontal beam runs almost parallel to the floorboard seam, while diagonal braces point inward like arrows converging on the worker’s bowed head. Even the stones of the wall stack into small, irregular rectangles that echo the larger carpentry. With a restrained hand Matisse builds a network of right angles and oblique thrusts that stabilize the space and slow time. Compositionally, this is a study in how geometry can make quiet.

Light And Tone As The True Narrators

There is a single narrator in this story: light. A dusty beam entering from the right skims across the loom, revealing form not in bright highlights but in low, granular gleam. The color temperature reads cool where day leaks through the door and window and warms into amber where light strikes wood. Matisse organizes the painting in tone—deep shadows under the loom; middle grays in the wall; half-lights on the posts; a concentration of nearer whites on the rolled cloth and the window. The figure’s face is left in shadow, but the slanted plane of the shoulders catches enough light to establish presence without portraiture. Tone does the work that color will later amplify in his career.

A Palette Of Work And Dust

The color scale is earthbound: raw umber, burnt sienna, gray stone, tarry blacks, and threadbare creams. The dominant sensation is wood aged by hands and weather. Greens and reds are absent; blues, if present, are so muted they sink into the air. This palette is not a lack; it is a choice that honors the subject. A flamboyant chroma would have falsified the room’s workday. The near-monochrome compels us to feel small differences—how a beam’s end carries a warmer note than the cool face of the post beside it, how a patch of whitewash on the back wall leans slightly blue. The effect is like listening to a quiet voice: you lean in.

Brushwork That Feels Like Joinery

Matisse’s handling here is not the buttery spread of his Nice interiors. Paint sits sturdily, describing mass rather than glare. On the posts, strokes travel with the grain so that wood looks planed rather than polished. The stone wall receives choppy, irregular touches that mimic the roughness of mortar. The rolled textile is built in broader, rounded strokes that lift off the surface and fall back again, as if to imitate the weight of cloth on the bar. Where edges meet—post against door, beam against ceiling—the painter slightly feathery edges to suggest air and dust. The brush, in short, behaves like a joiner’s tool, giving the room a tactile credibility that reads even from a distance.

The Human Figure As The Center Of Gravity

The weaver is not individualized, yet the painting bends toward this person. The bowed head, the concentration implied by the hunched posture, and the centered placement behind the loom suggest a mental absorption that commands respect. Because the face is obscured, the body speaks through angles and weight. There is nothing picturesque or sentimental here; the figure is neither romanticized nor pitied. The dignity arises from attention—the weaver’s to the task, and Matisse’s to the weaver. In that doubled attention the painting proposes its ethics.

Sound, Motion, And The Rhythm Of Work

The image is still, but viewers can hear it. An imaginary soundtrack pulses: the clack of the shuttle, the thump of the batten, the soft sawing of pedals, the faint rasp of cloth winding. Matisse achieves this audio illusion through repetition of forms—the alternating uprights, the evenly spaced rafters, the recurring rectangles. Patterns in shape create an expectation of patterned sound. Even the positions of darks and lights behave rhythmically, so the eye beats a measure as it moves. This is a visual poem about labor’s cadence.

Material Culture And The Ethics Of Craft

Brittany in the 1890s still carried a micro-economy of home and village craft. Weaving measured time differently than factory hours; it integrated family, season, and local sale. By painting a weaver in situ rather than in a staged studio scene, Matisse draws attention to a non-Parisian value system: work embedded in place. The stone wall is not backdrop; it is history hardened into matter. The loom has been repaired and handled; its corners have softened under fingers and rope. The painting’s respect for the room’s worn surfaces amounts to a social vision. Modern life can be seen without caricature, and dignity can be recorded without sentimentality.

A Dialogue With Painting’s Own Making

Weaving parallels painting at every turn. Both require warp and weft—structure and surface, drawing and color. The loom’s uprights correspond to the stretcher bars of a canvas, the warp threads to drawing lines, the weft to layers of pigment. The weaver’s concentration mirrors the painter’s, and the rolled cloth at right stands in for a scroll of prepared linen. Matisse, by placing the loom so prominently, is saying something about the logic of construction that he will carry into his boldest experiments. When he later cuts painted papers into interlacing rhythms, the remembered architecture of this loom will be there in ghost form.

Space As A Humane Frame

Technically, the spatial solution is subtle. The posts near us are slightly larger than perspective might demand; the result is not distortion but a gentle enclosure, as if we had stepped just inside the threshold and paused. The doorway and window do not open onto a detailed outdoors; they serve as abstract planes of light contrasting with the workshop’s earth. Space, then, becomes humane rather than optical. It wraps the worker in a shell of protection and lets light be an invited guest rather than a dominating force.

Comparisons That Clarify Matisse’s Direction

Place this painting beside a Dutch interior of a lace maker or a smithy by Courbet and you see affinities: a social respect for labor, a low key of color, an emphasis on the argument between light and dark. Yet Matisse’s picture is less anecdotal and more architectonic. There are no scattered props or narrative incidents; the walls are not loaded with moralizing detail. What counts is how the room is built—not only in life but on the canvas. The young painter, studying tone from the old masters, has already begun to simplify.

Evidence Of The Future In A Brown Palette

It takes little imagination to sense the future Matisse inside this sober room. The strict divisions of dark and light anticipate the flat, declarative planes of his Fauvist years. The love of textiles is already present, but as an origin rather than a decoration. The repeated rectangles, aligned like modules, foreshadow the compositional clarity of his Nice interiors and, later, the crystalline order of the cut-outs. Most tellingly, the painting’s moral quiet anticipates the serenity he sought in all his mature work. Even when he fills a room with red, the spirit of this Breton workshop—its poise, its earned calm—remains.

The Door And The Window As Moral Agents

Why include both door and window? Their roles are not merely descriptive. The open door promises circulation, air, perhaps a neighbor’s voice; the window gathers light into a cool square, a measured abundance. Between them the weaver sits, choosing to remain at the task. The painting honors that choice without judgment. It suggests that freedom is not flight but the ability to inhabit one’s craft with depth. This quiet moral of agency is woven into the structure of forms rather than spelled out as anecdote.

The Drama Of Edges

Look at how carefully Matisse modulates edges. Where the loom meets the floor, he softens contours so the wood sinks in. Where the post crosses the doorway, the edge sharpens, creating a crisp silhouette that catches the eye. Around the figure’s hat the edge flickers slightly, a little vibration of dark against mid-tone that implies motion. The window’s inner edge is the sharpest in the painting, rightly so: it is the place where outside light meets inside shadow, the hinge of the room’s illumination. These edge decisions are not technical niceties; they are how the painter tells us where to look and how long to stay.

Time, Wear, And The Poetics Of Use

Objects here have biographies. The loom’s platform shows scrapes; a beam has a lighter patch where hands have polished it; the rolled cloth’s first layers appear cleaner than the dusty outer ones; stone blocks register irregular lime. Matisse paints these signs of use with reserve, which paradoxically makes them more eloquent. He reminds us that beauty sits in the patina of use, in the human trace cooperating with matter rather than conquering it. That insight will later allow him to celebrate the worn arm of a chair or the faded corner of a carpet with the same dignity he gives a face.

The Body At Work As A Kind Of Devotion

Religious overtones arise without iconography. The loom’s posts could be read as a simplified rood screen; the weaver’s bowed head takes on the hush of prayer; light falls from the right like a visiting grace. Matisse does not preach; he suggests that sustained attention to a craft can be sacramental. This view aligns with his own attitude toward painting as a daily fidelity rather than a sequence of heroic breakthroughs. The Breton room becomes a chapel of labor.

What The Painting Teaches Viewers About Looking

“The Breton Weaver” trains the viewer’s eye in the ethos Matisse prized. Slow down, it says. Attend to relationships. Let small differences of tone and edge and temperature carry large meanings. Allow structure to soothe. Later, when he offers rooms soaked in red or arabesques of paper pinned to the wall, that same discipline will be beneath the dazzle. To understand the later Matisse fully, one must first understand the chastity of this early austerity.

A Conclusion Woven Of Wood, Stone, And Light

This painting is more than an ethnographic visit to Brittany. It is a self-portrait in disguise: a craftsman inside his chosen architecture, building a work thread by thread. Matisse’s future would explode with color and patterned cloths, with the sensuous ease of cut paper, but he would never abandon the lesson learned here—that harmony arises from structure, that light deserves patience, and that a human being bent over a task can dignify a whole room. “The Breton Weaver” is, finally, a hymn to making, sung softly in browns and grays, steady as the beating heart of a loom.