Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

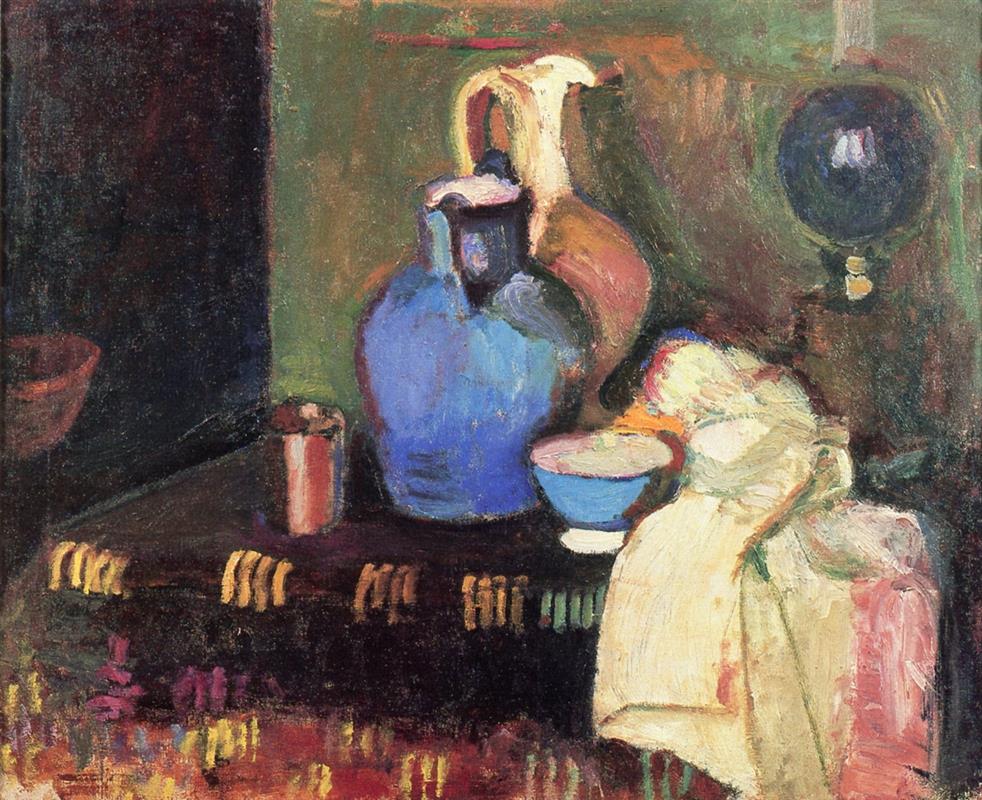

At first glance “The Blue Jug” appears homely: a big pottery vessel, a folded cloth, and a few modest items arrayed on a dark surface. Look longer and everything starts to move. The jug swells forward like a living shape, its cobalt skin vibrating with violet shadows and milky highlights. The draped cloth breathes with strokes of cream, green, and pink. The tabletop, far from inert, glows with small dashes of yellow that suggest reflected lamplight or a patterned textile. Matisse is not cataloging objects; he is constructing a world where color, temperature, and touch carry the burden of representation.

Historical Context

The date of 1899 places this canvas at a hinge in Matisse’s development. He had passed through academic training and a phase of muted tonal realism and was now absorbing the lessons of Cézanne’s constructive color, the Nabis’ decorative surfaces, and the Divisionists’ belief in optical mixture. He had recently painted in Corsica and the Midi, encounters that lifted his palette. In “The Blue Jug,” these influences crystallize: forms are built by adjacent planes rather than outline, pattern becomes structural rather than ornamental, and every dark remains chromatic. The picture is a small manifesto written in household things.

Subject and Studio Setup

The motif is a tabletop arrangement staged against a wall that reads as a patchwork of warm olive, umber, and russet. The titular jug dominates, a heavy-bellied vessel with a narrow neck and a dark mouth. A pale pitcher leans behind it, a small blue-and-white bowl sits at its side, and a cream-colored cloth, loosely folded, tumbles off the table edge. A stubby jar, perhaps a paint tin or canister, holds down the left flank. At the far right, the faint silhouette of a spherical object on a small stand suggests an oil lamp or a reflective globe. The stage is intimate, but the objects are not cute; they are weighty, handled like actors with presence.

Composition and Armature

The composition locks together around an emphatic pyramid. The blue jug forms the central mass; the pale pitcher rises behind like a secondary peak; the cloth descends toward the lower right in a sweeping diagonal that counters the vertical push of the vessels. The small bowl bridges jug and cloth, and the stubby jar anchors the left edge, preventing the scene from tipping. Matisse sets most of the weight slightly off-center, creating a subtle imbalance that keeps the eye moving. The back wall is not a flat backdrop; its shifting fields of color and a dark recess at far left create a shallow stage of overlapping planes. With very few shapes the painter achieves a secure, legible scaffold that invites chromatic daring.

Color Architecture

Color is the engine that turns description into experience. The jug’s cobalt body is not a single blue; it is a stack of neighboring temperatures—cobalt glazed with ultramarine shadows, cooled by violet at the rim, warmed by blue-green reflections near the base. The cloth refuses to be white; it is a quilt of creamy yellows, cool mints, and rose tints that answer the surrounding environment. The tabletop is a deep brown built from maroons and bottle greens, yet it sparkles with short, lemon strokes, as if a patterned runner or reflected glow were skipping along its surface. The wall compounds olive greens and red-browns; those complements make the jug’s blue ring like a bell. Every pairing is strategic: blue against umber, cream against deep green, rose beside olive. The harmonies do not decorate the objects—they build them.

Light and Atmosphere

Illumination seems to fall from the right, perhaps from a lamp or window beyond the frame. Instead of traditional highlights and cast shadows, Matisse stages the light as shifts in temperature. Where the jug turns toward light, cobalt blooms into lighter, milkier notes; where it recedes, blue sinks into violet and wine-dark edges. The cloth drinks light along its ridges, answering with buttery strokes, then cools to mint in the folds. The wall absorbs and returns warmth, its olive planes nudging the jug’s color toward green in spots. There is no theatrical spotlight; the air is warm and wide, a studio light that pulls every object into the same climate.

Brushwork and Surface

Material character is performed, not merely indicated, by the brush. On the jug, long, curved strokes wrap the belly, tightening where the form turns and spreading where it flattens. The cloth is painted in short, broken touches that mimic creases and the softness of fabric. The table’s dark field is laid broadly, then animated by small perpendicular dashes, a quiet shimmer that keeps it from becoming a dead pool. The wall is scumbled, its pigments dragged thinly so earlier layers glow through; this softens the distance and prevents the background from competing with the central mass. Throughout, a modest impasto catches actual light, so highlights are not illusions alone—they are physical ridges.

Drawing by Abutment

One scarcely finds a drawn contour. Edges arrive where one color presses against another. The jug’s outline is secured by the meeting of cobalt against warm umber, or blue-green against the pale cloth. The bowl’s rim is not inked; it appears where a band of pale violet kisses a darker interior. The cloth’s folds are seams of temperature—warm cream turning to cool mint—rather than graphite-like lines. This drawing-by-abutment keeps the surface coherent under one atmosphere and lets Matisse adjust weight and depth by tiny shifts in value and hue.

Space and Depth Without Linear Perspective

Depth unfolds as a set of stacked planes. The table’s near edge is inferred from the cloth’s descent and from the way yellow dashes terminate at the picture’s lower margin. The jug overlaps the bowl and pitcher; the little jar sits slightly forward but loses contrast where it meets the recess, signaling distance. The wall reads as a flattened patchwork that recedes by virtue of lower contrast and thinner paint. There is no vanishing point and no measured grid, yet the space feels inhabitable because overlaps and temperature steps do the work of perspective.

The Blue Jug as Protagonist

The jug is both object and color-event. As form, it is weighty and calm, its belly planted on the tabletop like a figure with gravity. As color, it is a resonator. It collects reflections from the cloth, spit from the warm wall, and darker notes from the recess to the left, synthesizing them into a coherent blue body. The small cap of near-black at the mouth gives the mass a necessary punctuation. The jug does not simply sit in the studio; it metabolizes the studio’s light, turning neighboring hues into its own speech.

The Cloth as Counterweight

The cloth offers the painting’s most complex temperature play. Along the outer fold, creamy yellows approach the warmth of the wall; inside creases, mint and pale blue lean toward the jug’s cool. Patches of unexpected pink sit at the corner, tying the cloth to the neighboring bowl and to red notes elsewhere in the painting. Script-like ridges along its edge act as visual punctuation, echoing the small yellow dashes on the table. This fabric does not just offset hardness with softness; it stabilizes the chromatic system and propels the viewer’s eye from lower right back into the center.

Decorative Pattern as Structure

The little serried strokes running across the table read like a woven stripe or the glint of light on a textured surface. Instead of a mere ornament, this pattern stabilizes the plane, telling the eye that the dark field is horizontal and expansive. Similar marks appear, stressed and diminished, near the bottom edge, creating a rhythmic echo that carries the viewer across the entire width of the picture. Matisse learned from the Nabis that pattern can be load-bearing; here it is the quiet architecture that keeps the still life from sinking into the dark.

Dialogues with Influences

Cézanne’s constructive color is everywhere: the jug turns by neighboring planes rather than blended tone; the bowl’s volume is a halo of cool and warm patches. From Bonnard and Vuillard, Matisse borrows the confidence to convert interiors and tabletops into decorative fields where pattern and object share status. Divisionism’s lesson—that optical mixture can energize a surface—appears in the way small dashes of yellow and mint vibrate against maroon and green; yet he rejects the mechanized dot in favor of strokes that flex with each substance. A faint memory of Gauguin’s synthesized surfaces lingers in the simplified shapes and high-key complements, but Matisse’s touch remains more observational, less symbolic. The painting is a negotiation rather than an allegiance.

Materiality and Studio Practice

“The Blue Jug” feels painted quickly but not carelessly. Underlayers peek at the margins, suggesting the picture was built in passes: broad masses first, then smaller accents, then retouching to tune edges. The paint film varies in thickness—dense on the jug and cloth, thin on the wall—so that physical weight and pictorial weight coincide. This calibration is crucial; heavy paint on the background would fight the central forms, while thin scumble on the jug would rob it of presence. The decisions are structural as well as expressive.

Rhythm and Movement

Despite the stillness of the subject, the painting moves. The eye circles the jug, falls into the bowl, glides down the cloth, answers the little yellow beats across the table, and returns via the warm pitch of the wall. The rhythm is musical: a sustained cobalt chord at the center; syncopated yellow notes on the dark ground; a warm, low drone from the umbers and olives behind. This orchestration of speeds and values is how Matisse animates a tabletop without anecdote.

Emotional Register

The mood is intimate and concentrated rather than sentimental. The warm studio air, the burnished wall, the calm jug, and the thrown cloth all speak of work paused—a moment when objects hold the vestiges of human touch. The palette is rich but not gaudy; its saturation is tempered by deep grounds and a coherent light. If there is drama, it lies in the conversation between cobalt and umber, cream and green, not in narrative incident.

How to Look Slowly

Enter at the lower right corner where the cloth bends over the table edge. Note how creamy ridges catch actual light, how minty strokes cool the shadowed fold, and how a pink glimmer ties to the bowl. Follow the cloth’s arc to the small bowl; see the thin band of lavender that defines its rim without a line. Slide into the cobalt jug; count the temperatures, from green-tinged reflections near the base to violet shadows at the neck. Step back to the little jar on the left and feel how its pale cylinder punctuates the dark recess. Let your gaze rise to the pale pitcher behind the jug and then into the mottled wall, where olive and russet exchange quiet heat. Finally, sweep across the tabletop and register the yellow marks as a steady beat that carries you back to the jug.

Relationship to Matisse’s 1898–1899 Still Lifes

Viewed alongside “Fruit and Coffee-Pot,” “Still Life with Oranges,” and “Still Life with Pitcher and Fruit,” this canvas clarifies a method: few shapes, decisive contrasts, and edges that are seams of temperature. “The Blue Jug” may be the most architectonic of the group. Its central mass is a single, commanding form that lets Matisse test how far color alone can project weight and volume. The discoveries here—chromatic shadows, patterned planes as structure, drawing by abutment—will travel easily into landscapes and figure pictures over the next years.

Why the Blue Jug Matters

The painting’s importance lies not in subject but in proof. It proves that color can do everything—model bodies, imply distance, capture atmosphere—without surrendering to black outline or heavy tonal shading. It proves that pattern can carry structure and that different handwritings of paint can enact different materials. It proves, finally, that intimacy of scale need not limit ambition; in a few square feet of canvas, Matisse rehearses the logic that will soon sustain far more audacious harmonies.

Conclusion

“The Blue Jug” is an early, persuasive demonstration of Matisse’s chromatic intelligence. A handful of studio objects become a system of precise relations in which warm and cool generate form, brushwork performs matter, and space opens without rulers. The jug is monumental because color makes it so; the cloth is luminous because it borrows light from everything around it; the tabletop pulses because small, rhythmic marks enliven darkness. In this modest still life, the young painter discovers that the everyday can bear the weight of modern art when tuned by exact color relationships. The road to Fauvism runs directly through this cobalt vessel, and it hums.