Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

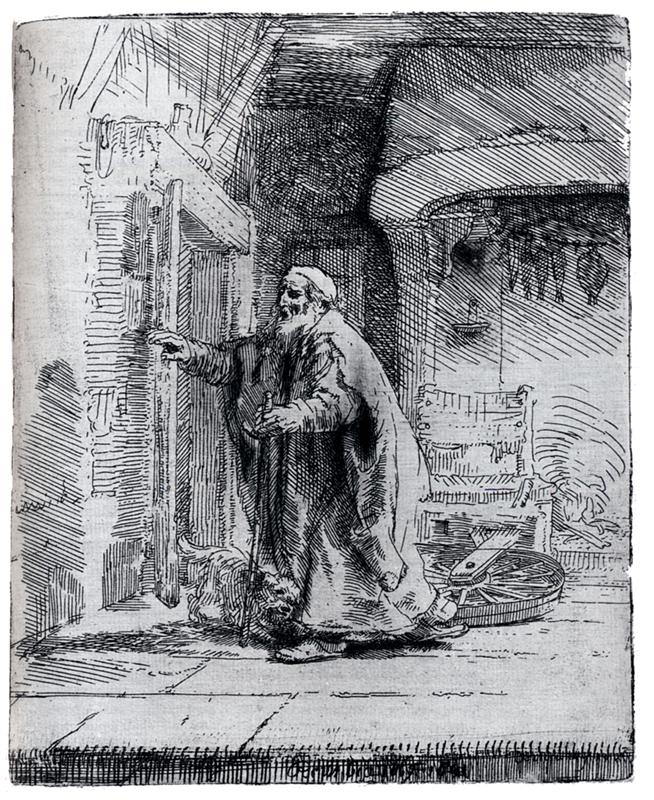

Rembrandt’s “The Blind Tobit,” etched in 1651, compresses an entire chapter of human experience—fear, hope, deprivation, and piety—into the small rectangle of a domestic threshold. The scene is intimate: an elderly man in a long robe and skullcap reaches toward a doorframe, his cane angled forward, his body feeling for the world he can no longer see. Light rakes in from the left, describing the wood grain of the jamb and the rough floor stones while leaving deeper interior spaces in velvety mid-tone. A chair and a spinning wheel sit idle; sprigs of hanging herbs darken the back wall. On the floor a small dog crouches near the old man’s hem, as if registering the stir of a visitor. The figure is Tobit, the righteous exile from the Apocryphal Book of Tobit, whose sudden blindness and eventual healing made him a potent emblem of faithful endurance for early modern viewers.

What matters in Rembrandt’s rendition is not spectacular miracle but the meticulous staging of a moment just before change. The etching shows Tobit’s hand at the lintel and his face tilted to the light, poised between resignation and alert expectation. Through etched line and drypoint burr, Rembrandt gives the story its material ground—planks, nails, cloth, dust—and discovers in that ground a moral air that makes the image more than illustration. It becomes an image about how people move through darkness by touch, memory, and hope.

The Book Of Tobit And The Choice Of Moment

In the biblical narrative, Tobit is a pious Israelite living in exile at Nineveh. He is blinded when sparrow droppings fall into his eyes, a detail at once humble and devastating. Ruined, he sends his son Tobias on a journey to retrieve a deposit; the Archangel Raphael, disguised as a guide, accompanies the boy, who returns with a remedy from a fish that will cure Tobit’s eyes. Artists have long loved the episode of Tobias traveling with the angel and the faithful dog beside them. Rembrandt instead chooses a subtler interval: the blind father at home, waiting, his life suspended between the catastrophe of loss and the promise of restoration. In narrative terms the image sits just before Tobit 11, when the ointment made from fish gall is applied. By withholding the cure, Rembrandt dignifies the long, ordinary time in which most lives are actually lived—the time of waiting.

Composition And The Architecture Of A Threshold

The composition pivots on the doorframe. Thick, squared timbers assert a vertical grammar against which the old man leans. At the threshold floor stones give way to the rough plank interior, a visual seam that marks the border between public and private, exposure and shelter, blindness and light. Tobit is placed slightly off-center, so that his outstretched right arm and the cane in his left create a shallow triangle leading to the jamb. This triangulation tightens the space around him, turning the viewer’s focus into a narrow, tactile zone where wood and flesh meet. Behind him, the bench and spinning wheel consolidate into a compact wedge that anchors the right side of the plate; above them, linear hatchings arc beneath the eaves and gather into a darker canopy. The whole design breathes with inward pressure and outward pull—the pressure of walls and the pull of light.

Etched Line, Drypoint Burr, And The Feel Of Things

Rembrandt’s technical language carries meaning. He draws the robe with long, drooping strokes that double and cross, so the cloth looks heavy, almost damp with use. The cane is a quick, confident line that cuts free of the robe like a signature of intention. The doorposts are built from firm verticals engraved with parallel marks that mimic the grain of sawn wood; the nails are tiny, blunt accents, proof of a house assembled by human hands. In the deep interior, drypoint burr produces a soft, felted black that swallows detail. The result is not just contrast but touch. Your eye translates lines into textures: splintered timber at the hand, wool at the wrist, stone underfoot, coarse thatch shading the rafters. Rembrandt here proves that etching can be tactile without illusionism; the material facts of line are themselves the sensation of matter.

Light, Blindness, And The Ethics Of Seeing

One of the most profound choices in the print is its lighting. Illumination floods the threshold and strikes the side of Tobit’s head and robe, as if the world outside were clear and the interior clouded. We observe a paradox: the blind man is closest to the light. This is not a sentimental metaphor but a felt arrangement of values. The light does not theatricalize; it reveals the means by which Tobit continues to navigate—a door he can stroke, a cane he can angle, a floor he knows with his feet. In Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro, the ethics of seeing become central. Sight is one way of knowing; touch, habit, and faith are others. The print honors what remains when sight fails.

Gesture, Posture, And The Psychology Of Waiting

Tobit’s body reads with eloquent clarity. His right arm extends toward the door but does not yet grasp it; the hand hovers, fingers spread to taste the air and catch the edge. His left arm, drawn slightly back and down, steadies a stick that is more compass than crutch. The weight sinks to his back foot; the forward foot is tentative, its heel still lifted. This choreography holds a precise mood: he is already in motion and not yet moving. His mouth is parted, suggesting breath drawn at the prospect of a voice. The fragile readiness embedded in these micro-gestures is the drama. The story’s theology—that divine help returns to the faithful—arrives at the level of posture.

The Dog, The Chair, And The Spinning Wheel

Rembrandt salts the scene with domestic specifics that complicate and enrich its meaning. A small dog, often a companion in Tobias scenes, crouches just inside the door. Its presence compresses hope and loyalty into an animal shape: the dog can sense what its master cannot see. The empty chair implies absence and interruption, a place waiting for a sitter who has risen to answer a call. The spinning wheel, leaned aside, refers to labor in the household, likely Anna’s work. It is an emblem of continuity—the making of thread that keeps daily life from fraying—now momentarily stilled by Tobit’s reaching. These objects ground biblical narrative in the rhythms of a working home; their respectful rendering is a moral position.

Space As Moral Weather

The room is small, yet the space feels vast where it matters: at the lit threshold. Rembrandt’s sparse interior lines open into a gulf of white stone, giving Tobit a patch of ground as clear as a courtyard. The background walls compress into darker planes that feel protective but not comforting; they are the architecture of limitation. Above, the thatch curves like a sheltering palm, but the dramatic arch of hatched darkness through the middle distance also reads as a cloud shadow passing through the mind. Space in the print is not neutral; it is moral weather—clearning, overcast, edged with light.

Theological Resonance Without Illustration

Rembrandt resists the temptation to show the angel or the fish or even Tobias’s approach. He trusts a single, human scale. That trust enables the sheet to carry theological resonance without becoming a literal diagram. The faithful old man expects the world to speak again, and his body arranges itself to meet that speech. The print becomes a parable about response: grace arrives; one must reach toward it. This is doctrine as behavior, religion as posture rather than pageantry.

The Face At The Edge Of Revelation

Tobit’s face is small but charged. The etched lines around the eye sockets describe hollows rather than pupils; the blunted nose and open mouth share a family resemblance with Rembrandt’s sympathetic beggar heads. Yet this is no genre type. The features hold the sober gravity of a man accustomed to prayer and accounting, not self-pity. The hint of a furrow between the brows suggests thought even now—a man calculating steps, scanning his memory of the room. The head tilts toward the light with barely measurable hope. Rembrandt builds that hope into the architecture; it is the angle at which the face meets the bright jamb.

Time, Sound, And The Suspended Instant

Everything in the print listens. The dog pricks inward; the man’s hands and mouth open; even the door seems to ring with the suggestion of a knock. The etching thereby invites sound into its silence: a foot on stones, a boy’s voice, a familiar name. Rembrandt’s best narrative images choose instants that are both climax and prelude; what happens next is foregone and yet utterly alive. The suspension here echoes a broader human rhythm—the way change often announces itself a breath before it arrives.

The Lineage Of Rembrandt’s Tobit Images

Rembrandt returned to the Tobit story several times in drawings and prints, most famously in earlier etchings of Tobias and the angel on the road and in the large “Return of Tobias.” Compared to those, “The Blind Tobit” is spare and inward. Where other images celebrate the companionship of journey and the grandeur of miracle, this plate honors the private muscle of faith: the daily reaching. It belongs to the same family as Rembrandt’s humble biblical interiors—Anna spinning, the Holy Family in a room, Christ in the carpenter’s shop—where sanctity inhabits ordinary labor and light.

The Economy Of Means As Moral Aesthetic

A striking feature of the print is how much Rembrandt achieves with so little. There is no lavish plate tone, no crowded cross-hatching; the marks are legible, their intervals generous. Such economy is not merely stylistic. It is a moral aesthetic aligned with the narrative’s stripped condition. Tobit’s household has been reduced by blindness; the print refuses visual luxury. What remains—wood, fabric, stone, body, dog—is enough, and through that “enough,” grace enters. The viewer feels the dignity of sufficiency.

A Dutch Interior And The Ethics Of Care

Seventeenth-century Dutch viewers would have recognized the room as kin to their own: a practical house of wood and thatch, a space of labor and plain furnishings. By setting a sacred story inside recognizable architecture, Rembrandt enlarges the ethical field. Care for the blind, patience in adversity, faith as daily behavior—these virtues no longer belong to remote saints but to neighbors. The print becomes a civic image as much as a devotional one, a reminder that holiness is measured in how people hold doors and speak names in the dusk.

The Viewer’s Position And The Intimacy Of Address

Rembrandt places us just inside the room, a step or two from Tobit, level with his chest, close enough to hear him breathe. The intimacy creates a subtle obligation: to speak so that he knows we are there, to guide rather than gawk. Many of Rembrandt’s prints choreograph the viewer into ethical roles—witness, helper, participant. Here we are almost the returning child. The picture’s power emerges from that identification; it enlists rather than merely displaying.

Comparisons With Contemporary Printmakers

In the same decades, other printmakers treated biblical subjects with mannered architecture, packed crowds, or elegant bodies. Rembrandt’s contrary approach—domestic scale, weathered flesh, visible line—redefined what a sacred print could be. His “Blind Tobit” offers an antidote to the taste for spectacle. It suggests that spiritual gravitas lives where a robe drags the floor and a hand gropes for a latch. That argument influenced later artists who learned from him to trust small interiors and unidealized figures.

What The Dog Knows

The tiny dog is not a charming aside but an instrument of meaning. Its stance, huddled yet alert, bridges the old man and the invisible approach of Tobias. Animals in Rembrandt often act as registers of the scene’s real temperature; here the dog reads the air with more certainty than its master. The animal’s presence also nods to the narrative detail that Tobias travels with a dog. In the room, the pet becomes a promise compressed to fur and bone, a miniature of fidelity that tethers hope to the floorboards.

The Spin Of Tools And The Halt Of Time

The idle wheel beside the bench holds a soft metaphor. Spinning converts fiber to thread, time to cloth, repetition to sustenance. Paused, it stands for a life interrupted. Blindness has unspooled order; work has stopped. Yet the wheel is not broken; it can be taken up again. Its temporarily arrested circle rhymes with the open arc of the thatch and the rounded head of the cane. Circles in the print are not closed conclusions but potential motions. They are emblematic of the return that is about to happen.

The Print As Portable Consolation

Owning this etching would have meant keeping a small theater of consolation at hand. Its size makes it intimate; its subject makes it companionable in seasons of waiting and uncertainty. Rembrandt understood the pastoral capacity of prints—the way a sheet could travel into homes and become a daily meditation. “The Blind Tobit” gives a practice for such meditation: feel for the door, listen, keep the wheel near, let the dog warn, and tilt your face to light.

Why The Image Still Speaks

Contemporary viewers, even without the apocryphal book’s details, recognize the drama of impairment and the moral texture of care. We know rooms interrupted by illness, the sound a cane makes on stone, the expectation that reorganizes posture when a familiar step approaches. The print refuses distance; it acknowledges frailty as common ground. In a world that increasingly outsources spiritual themes to abstraction or spectacle, Rembrandt’s etching insists that holiness remains legible in the way a hand finds wood.

Conclusion

“The Blind Tobit” is among Rembrandt’s finest arguments for the sanctity of ordinary life. Through a choreography of touch and light, the print turns a small domestic threshold into the place where faith takes bodily form. Tobit’s outstretched arm, the waiting dog, the stilled wheel, the unassuming chair, the rough stone—all conspire to build an atmosphere of watchful hope. The moment is neither miracle nor catastrophe; it is the human interval between them, the duration in which most virtues are practiced. Rembrandt’s technical economy and ethical clarity make that interval visible and, more importantly, shareable. We stand in the room with the old man, we breathe his breath, and we learn—again—how to meet the world when we cannot see it.