Image source: wikiart.org

A First Look at “The Black Shawl” (1918)

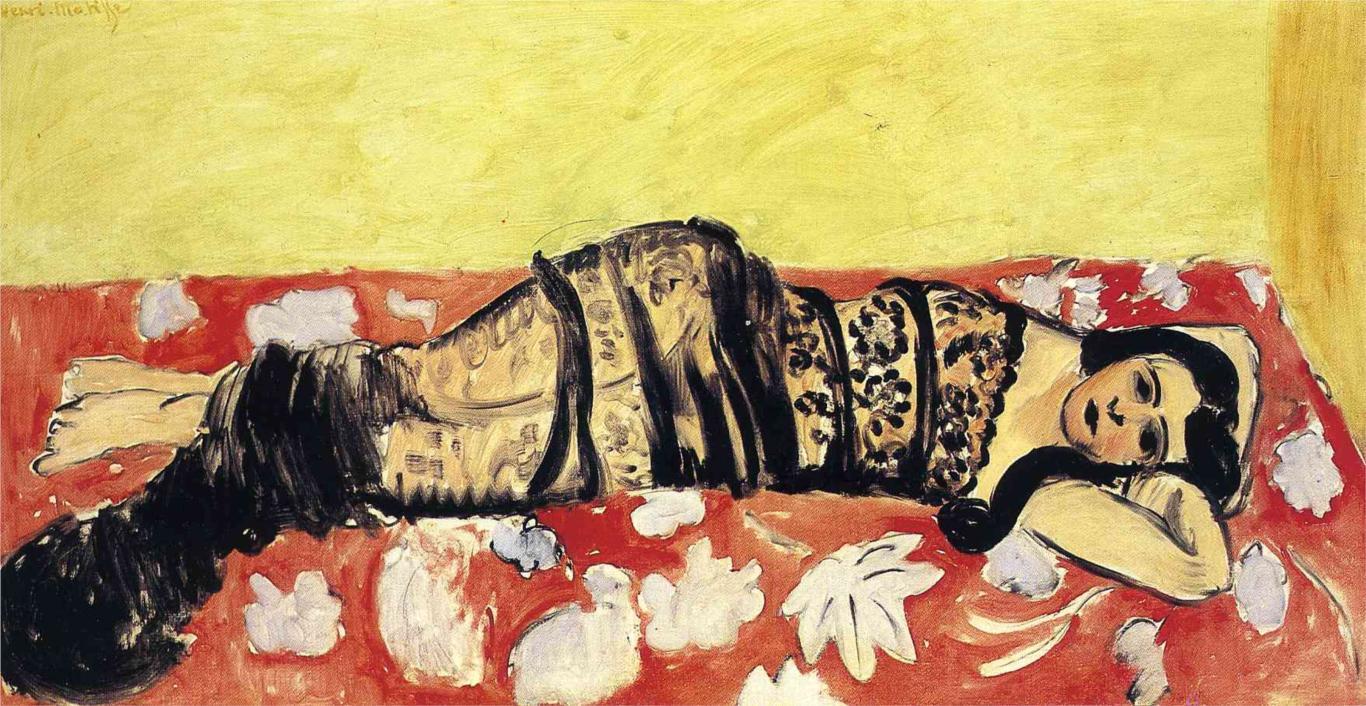

Henri Matisse’s “The Black Shawl” is a panoramic slice of calm, a reclining figure stretched across a red field of ornament beneath a soft, yellow wall. The woman is swaddled in a dark shawl, her head resting on a bent forearm, eyes closed or lowered into the privacy of daydream. Matisse lays the scene out with the lucidity that marks the dawn of his Nice period: few elements, large relations, tuned color, and the authority of black line. Instead of the theatrical saturation of early Fauvism, he gives us a measured chord—lemony yellow above, carmine red patterned with pale leaves below, and the deep blacks of hair and wrap that turn the figure into a long, legible silhouette. The effect is both intimate and monumental, as if a moment of rest has been composed into a lasting design.

The Moment in Matisse’s Career

Painted in 1918, the canvas belongs to the first wave of interior scenes that opened Matisse’s long Nice period. After the structural severity of the mid-1910s, he pivoted toward steadier light, shallower space, and a decorative intelligence that could convert everyday rooms into harmonies. “The Black Shawl” prefigures his odalisque imagery of the 1920s without relying on its profusion of patterns and props. Here, the set is reduced to two planes and one body, a spare stage on which color and contour do the storytelling. The painting demonstrates his belief that serenity could be modern—achieved not with academic finish but with exact relationships of hue, value, and line.

Composition: A Horizontal Lullaby

The format is an unusually wide rectangle, and Matisse exploits it by aligning the figure with the canvas’s long axis. The body flows from left to right in a single sweep: feet tucked, knees raised, hips and ribs described by the shawl’s broad bands, chest easing into an exposed shoulder, head resting at the far end like a period at the end of a sentence. The near-horizontal posture quiets the image at once. The only marked diagonals are the curves of the legs and the soft wedge of the pillow under the head, just enough inflection to keep the line alive. Above the figure, a long band of lemon yellow runs the length of the canvas; below, a red expanse repeats the rectangle’s breadth. The whole reads like three interlocking plainsong notes—yellow, red, and black—held in calm counterpoint.

Pattern as Ground, Not Noise

The red support on which the model reclines is ornamented with large, pale leaf forms. They are not meticulously drawn; they are stenciled sensations, floating shapes that repeat at generous intervals. Their job is structural. They scale the red plane so it does not read as a void, and they echo the organic curves of the figure without competing for attention. Because the motifs are white and gray rather than bright, they lighten the red without jolting it. Matisse uses pattern like a musician uses a drone: a steady underpinning that enriches the melody stretched across it.

Palette: Tempered Heat and Living Black

Color carries mood in this painting, but not by shouting. The yellow upper field is a soft citron, warmed by thin applications that let the ground breathe; the red lower field is broken with lapses where undercolor and brushwork flicker through. The body itself is modeled from a limited range of warm ochres and cool grays, enough to turn form without heavy shadows. The shawl and hair supply the crucial black. In Matisse, black is never simply an outline; it is a positive, light-catching pigment that anchors the harmony. Laid thickly across the drape, it corrugates into ridges that pick up glints from the studio light; drawn swiftly along the figure’s edge, it becomes calligraphy that organizes the silhouette. The painting glows because these blacks hold the warm fields in check, the way a bass line stabilizes a chord.

The Figure as Silhouette and Volume

The reclining woman is legible at two distances. From across the room, she reads as a single, flowing shape cut from the red ground by decisive black. Up close, the body resolves into contiguous planes—the curve over the knees, the soft valley of the hip, the slope of the shoulder, the oval of the face—each tuned by a small change in temperature rather than by weighty modeling. The head is limned with a strong dark that sweeps into the hair and loops under the forearm, a single stroke that seats the face in the pillow and seals the composition’s right edge. Matisse avoids anecdotal detail. There is no jewelry to read, no bedstead to parse. Character arrives through pose and through the exact posture of mouth, eyelids, and cheek: restful but alert, interior without drama.

Space Flattened to Breathe

Depth is deliberately shallow. The yellow band above the red suggests a wall, but it is not pushed back with perspective cues; it is a flat plane meeting another flat plane at a seam somewhere near the model’s spine. That seam is not a hard horizon; it is softened by variations in the yellow paint, which keeps the picture from breaking into separate compartments. Because space is flattened, the figure doesn’t fall into a hole; she inhabits the surface like a design. This shallowness, a hallmark of the Nice years, allows Matisse to treat painting as a crafted object—color and line on a plane—while still delivering the sensation of air and flesh.

The Shawl: Weight, Rhythm, and Modesty

The black shawl is the picture’s engine. It wraps, piles, and bands the torso, creating alternating stripes of deep black and patterned beige that march across the body like musical measures. Those bands perform multiple jobs. Visually they state the volume of hips and legs while suppressing unnecessary information; emotionally they introduce modesty without stiffness; rhythmically they break the long form into pulses that keep the eye moving. The shawl’s blackness also converses with the hair and with scattered black accents along the outline, giving cohesion to the figure. In an otherwise warm chord, the wrap’s darkness is the cool counterbalance.

Brushwork: The Time of Making

Nothing in the surface is overpolished. The yellow wall is laid with broad, lateral strokes that leave soft ridges; the red ground shows fast, circular passes where motifs were blocked in and left to sit; the shawl’s blacks are slathered, their edges dragged and feathered by the speed of the stroke. Flesh is handled with restraint: a light scumble for the forearm, a warmer pass for the thigh, a small gray patch to tuck the ankle back. This visible making is not bravura; it is clarity. It allows the viewer to reconstruct the painter’s decisions and to feel the pace of the studio hour in the calm of the finished image.

Rhythm and Repose

The painting’s great achievement is to be both still and musical. The horizontal body quiets the composition, but the alternating bands across the shawl, the regular scatter of leaf motifs, and the curve-and-countercurve of hips and arm keep the image from congealing. The eye’s natural ride—from left foot along the dark drape over knees and hip, to the exposed shoulder and finally to the resting head—mirrors the breath of someone dozing: long intake, sustained pause, gentle exhale. Matisse often spoke of wanting painting to offer “balance, purity, and serenity.” Here he designs that serenity as a rhythm you can feel.

Between Fauvism and the Odalisques

Place this canvas beside Matisse’s earlier Fauve interiors and his later Nice odalisques and its position becomes clear. From Fauvism it retains the courage of large color fields and the refusal of storytelling. From the odalisques it anticipates the reclining pose, the long decorative ground, and the play between patterned textile and simplified body. But “The Black Shawl” stops short of the profuse ornament of the 1920s. The harmony is leaner, the contrasts bolder, the structure more legible. It is a hinge picture—a rehearsal of pleasures to come climbed down from the high temperature of the past.

The Ethics of Looking

A reclining female figure risks becoming cliché or voyeurism. Matisse counters that risk with privacy and respect. The model’s eyes are lowered; her face is composed; the black wrap asserts a limit. The painter does not intrude with descriptive inspection; he edits to essentials and offers the viewer the mood of a room rather than the invasion of a body. The image becomes less a scene of possession and more a study of repose, light, and relation—an ethic consistent with the Nice period’s cultivated calm.

Dialogues with Tradition

Echoes of tradition are quiet but present. The long, reclining figure recalls classical and Renaissance prototypes, yet the flattened space and patterned ground recalibrate that heritage for modern sensibilities. One might remember Ingres’s odalisques in the basic posture, but Matisse refuses both the porcelain finish and the cool distance; instead he opts for painterly touch and decorative logic. Likewise, Japanese prints whisper beneath the bold contour and the way color areas are allowed to remain unmodeled. Tradition here is not a set of rules but a vocabulary Matisse borrows to say something in his own grammar.

Edges, Seams, and Cohesion

Edges carry meaning throughout. Where the black shawl meets the red ground, the seam is often rough, a dragged line that suggests soft fabric settling. Where flesh meets textile, the join is brighter, a narrow band of light that seats the body in the bed while maintaining distinction. The seam between red and yellow is softer still, an atmospheric hinge that keeps the two planes in the same climate. Such tailored edges prevent the simplified forms from reading as pasted cutouts; they allow the painting to feel whole, airy, and made rather than engineered.

Material Evidence and Revision

Look closely and the painting admits its revisions. A curve along the knees re-drawn with a darker band, a motif on the red ground adjusted and partly obscured by later strokes, a hairline reinforced after the pillow was set. Matisse leaves these pentimenti visible. Their presence reassures the viewer that the balance we feel was not formulaic. It was discovered in the act, which is why the picture’s quiet has depth.

How to Look: A Guided Circuit

Begin at the left with the soft, pale feet, then track the thick black that wraps the ankles and rises over the knees. Notice how those black bands widen and narrow, announcing volume beneath. Let your eye climb the shawl’s alternating stripes to the warm stripe of exposed torso and the small bouquet of floral pattern under the shoulder. Continue to the face, framed by a loop of hair and rested on a white pillow, the calm pivot of the composition. Drift upward to the lemon wall, then sweep back across the red field, reading the pale motifs as a slow percussion. Complete the loop by returning along the body’s contour, where black line keeps time like a low drum.

Why It Still Looks New

The painting’s clarity aligns naturally with contemporary taste. Large, flat color fields read instantly; the palette is sophisticated; process is visible and honest; the shallow space anticipates photographic cropping and graphic design. Most of all, it trusts a small set of true relations—yellow above, red below, black across—to carry emotion. In a culture saturated with detail, such economy feels fresh.

Enduring Significance

“The Black Shawl” condenses a decade of Matisse’s discoveries into a lucid interior. He trades the spectacle of color for the poise of harmony, converts pattern from distraction into ground, and uses black not as outline but as a living structural pigment. The reclining figure is less a subject than a melody that allows the painting’s real theme—relation—to be heard. A century later, the picture still offers what the artist wanted paintings to offer: a refuge of balance and light, a place where looking becomes a steadying breath.