Image source: wikiart.org

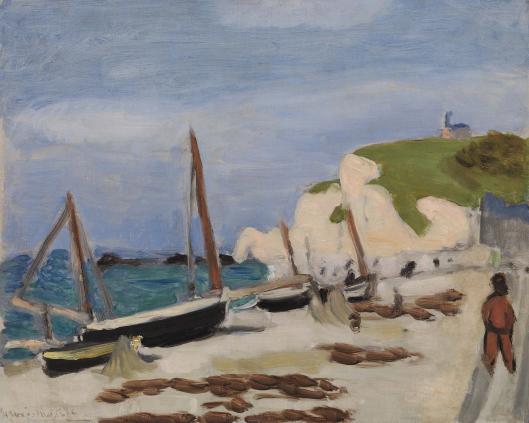

A Coastal Scene Held Together by a Single Dark Hull

Henri Matisse’s “The Black Boat” (1920) captures the quiet pulse of a working shore with remarkable economy. A narrow beach curves below chalk cliffs; nets lie in loose swaths on the sand; slender masts lean like reeds in wind; and, slightly off center, a single dark hull grounds the composition. The painting does not dramatize the sea’s power or the fishermen’s toil. Instead, it stages an ordinary morning of air, light, and readiness, when boats rest, gear is drying, and people drift along the strand. By using the black boat as a visual anchor, Matisse organizes a wide littoral space into a single, poised sentence—an image that holds together because every element is measured against that dark form.

Where and When: Normandy after the War

Painted in 1920, the scene aligns with Matisse’s postwar returns to the Normandy coast, whose chalk headlands and small fishing communities had already become touchstones of modern French painting. While earlier artists sought storms or blazing sunsets, Matisse preferred an even light that allowed structure to speak. In the years after the First World War he pared his language down: calmer palettes, clearer armatures, and a renewed intimacy with everyday subjects. “The Black Boat” belongs to this pursuit. It presents a coastal hamlet free of spectacle—a place defined by work, salt air, and the geometry of boats and cliffs.

What Meets the Eye at First Glance

The composition reads at once. A scrim of blue sky fills the upper half, brushed thin so that light seems to pass through the paint. The sea occupies a compact band at left, its greens pushed toward blue by a froth of short white strokes that mark a lazy chop. The beach spreads diagonally from lower left to upper right, gathering drift and nets into tawny patches. White cliffs rise beyond, topped by a green cap where a tiny chapel or cottage perches—an index of scale and a quiet note of human settlement. On the far right, a figure with bare back and rolled garments stands, as if paused between errands. The black boat, tilted slightly toward the sea, is flanked by other hulls; it is the one that holds the painter’s and our attention.

Composition as a System of Slanting Lines

Matisse constructs the picture with a lattice of diagonals and uprights. The shoreline sets the dominant diagonal, guiding the gaze from the black boat into the depth where cliffs and hillside recede. The masts, some upright and some canted, interrupt that sweep with a repeating rhythm that keeps the composition from sliding too easily into distance. Nets hang from spars, dropping vertical accents that echo the masts at a softer scale. Even the cliff edge, broken into chalky lobes, advances in steps that answer the rhythm of the masts. The figure at right closes the circuit: their posture mirrors the uprights while their shadowy shape balances the boat’s dark weight. The result is a structure that feels inevitable, as if the shore had arranged itself for clarity.

The Black Boat as Pictorial Anchor

The eponymous boat is more than a subject; it is the painting’s fulcrum. Its dark hull provides the strongest value contrast in the scene, and so it gathers attention without theatricality. Because we know roughly how large a small fishing boat is, the hull sets scale for everything else: the nets read as manageable lengths of rope and mesh, the white cliffs become massive yet believable, and the tiny chapel becomes properly distant. Matisse uses the boat’s angled keel to point toward the sea, a subtle arrow that brings movement into an otherwise stationary view. The boat makes the space readable and the day’s purpose legible: this is a shore that works.

Color and Light: A Maritime Palette in Quiet Balance

The palette is maritime but restrained—sky blues tempered with gray, sea greens cooled by white, chalk whites warmed with touches of ochre, and the deep black of the hull modulated with brown. Matisse avoids saturated punches; he prefers gentle harmonies that let the air feel breathable. The sky is thin, worked in horizontal sweeps that suggest high cloud and wind-smoothed atmosphere. The sea is a mixture of short strokes and longer pulls, its surface stitched with small, lively tilde-like whites to suggest a light chop. On the beach, warm creams and pinkish grays mingle with the nets’ brown to create a ground that is neither dusty nor wet, just sunlit and workable. Against this calm field, the boat’s black reads not as a hole but as a polished, serviceable surface that has met many mornings like this one.

Brushwork and the Life of the Surface

Every zone receives its own vocabulary of marks. The sky’s broad, horizontal sweeps keep attention relaxed. The water tightens into shorter, stacked strokes, making a plane that shimmers without detail. The cliffs are built from soft, rounded touches that preserve their chalky mass while acknowledging reflected light. On the beach, Matisse’s brush alternates between scumbling and decisive dabs to indicate nets, footprints, and patches of seaweed without enumerating each grain of sand. The boats are handled sparely: a linear stroke for a gunwale, a smudge for a sailcloth, a single highlight catching a curve. This economy of touch prevents the painting from turning anecdotal; it stays a construction rather than a catalog.

Space, Flatness, and the Honest Picture Plane

Although the painting describes clear recession—from foreground sand to distant chapel—Matisse protects the integrity of the canvas surface. He crops the boats so their masts and spars echo the painting’s edges; he keeps the sea in a contained band rather than a plunging vista; he flattens the cliff’s planes to broad, simplified lobes. These strategies keep the viewer aware of looking at paint, not peering through a window. Depth is present but disciplined. That balance—between observable world and painted surface—defines Matisse’s mature classicism.

Labor, Habit, and Human Presence

No figure hauls a net or pushes off, yet human activity saturates the scene. Nets are draped to dry, sails are furled, hulls are angled in readiness, and the lone figure at right turns as if to call to someone or to check a line. Nothing is dramatized, which is the point: life here proceeds by habit and coordination. The boats’ arrangement implies conversation and cooperation; the nets’ ordered disorder evokes practiced hands that know how gear should lie to dry well. Matisse dignifies this ordinary work not by romanticizing it but by giving it compositional centrality and clarity.

Cliffs, Grass, and the Chapel: Markers of Scale and Continuity

The chalk cliffs are more than a backdrop. Their pale, irregular masses report the coast’s geology and echo the sails’ shapes and the boats’ bows. The green cap of grass stabilizes the upper right corner and cools the sky’s blueness; it also holds a tiny built structure, likely a chapel or watchhouse, that brings scale and a sense of long continuity. The community implied by boats and nets is thus joined to another, older continuity of stone and faith, perched watchfully above the daily work.

Rhythm, Repetition, and the Music of Masts

One of the painting’s quiet pleasures is rhythmic. The masts repeat like beats, some vertical, some leaning, each with a slightly different interval. The nets’ drooping triangles rhyme with the cliff’s lumped forms. The ellipses of the hulls echo one another in diminishing scale as they recede, a chain of ovals that pulls the eye along the strand. Even the patches of weed or rope on the sand repeat with variation, like chords voiced differently. These repetitions make the scene feel heard as well as seen, a low maritime music conducted by wind and habit.

Weather and the Time of Day

The light suggests a temperate, early-to-midday hour: shadows are short and soft, the sea’s chop glints without glare, and the sky wears only light cloud. This weather supports Matisse’s project. In such conditions edges are honest, tones are readable, and color finds its center. The beach feels open to work, not pressed by heat or storms. The viewer can sense the day’s plan—boats ready, nets drying, a lull before tide or departure.

Dialogue with the History of the Motif

Fishing boats on beaches were a familiar modern motif, painted by Courbet, Boudin, Monet, and many others along the Channel coast. Matisse’s version is notable for its restraint. Rather than indulging the sparkle of sails in strong sun or the drama of departures, he studies how a few forms—hulls, masts, nets, cliffs—can be placed to carry a wide, breathable space. He compresses anecdote to keep the painting’s grammar clean. This self-limitation is not an absence of feeling; it is a channel for it. The warmth we sense arises from rightness of relation more than from narrative incident.

Relation to Matisse’s 1920 Coastal Series

“The Black Boat” converses with the artist’s other 1920 coastal canvases: views of cliffs with heaps of fish, a single eel on seaweed, two rays resting on the shingle, and an arch seen close with a small sail. All share a disciplined armature and a preference for everyday motifs. Compared to the still-life-on-the-beach pictures, this painting shifts attention from the catch to the vessels and gear—the instruments rather than the harvest. The mood is anticipatory rather than reflective: boats will go out, nets will be cast, work will resume. Across the series, Matisse tests how different anchors—the black hull here, a pile of fish elsewhere—recalibrate the same coastal space.

Meanings That Grow Naturally from the Scene

While the painting resists allegory, it carries meanings that emerge from its structure. The black boat reads as readiness, a compact shape tuned to purpose. The nets suggest interdependence: strands that only function as a woven field. The chapel, small and high, implies memory and measure, a point by which sailors gauge position and by which communities gauge time. The cliffs proclaim geological endurance, against which daily preparations gain poignancy. None of these meanings are hammered; they arise because the picture is constructed with care.

Material Presence and the Pleasure of Looking Up Close

Up close, the surface is alive with varied thickness and speed. Thin paint in the sky lets the ground tone inflect blue into gray; thicker strokes along the hull catch actual light, making the boat’s form palpable; the cliffs are scrubbed in gently, their edges vibrating where sky meets chalk. Even the prints of the brush on the sand contribute to the illusion of footfalls and raked surfaces. The painting rewards slow looking, the kind of attention its subject—careful preparation—quietly honors.

Why This Painting Feels Fresh a Century Later

The canvas remains fresh because it demonstrates how modest means can sustain a wide field of feeling. It offers a coastal morning without sensationalism, trusting the viewer to complete the experience from lived memory: salt in the air, ropes rough with brine, the hollow clack of masts, the dull shine of tarred hulls, the hush before a boat noses into water. The modernity resides not in novelty of subject but in the clarity of means. In an age of visual noise, the painting’s calm grammar feels bracing.

A Painter’s Ethics: Giving Ordinary Work Its Due

Matisse often spoke through choices rather than manifestos. Here his choice is to give the day’s tools—the black boat, the drying nets—the compositional honor usually reserved for spectacle. He grants ordinary work the dignity of balance and space. The ethic is simple and profound: attention is a kind of respect. By attending carefully, he allows viewers to feel the coast as those who live there feel it—not as tourists awaiting drama but as people who know the tide chart and the weight of wet rope.

Conclusion: Readiness at the Water’s Edge

“The Black Boat” is an essay in readiness. Its structure—diagonal beach, upright masts, bright cliffs, and the single black hull—states the facts of a working shore with serenity and poise. Color hums in a quiet register, brushwork switches dialects to match sky, water, chalk, wood, and cloth, and space deepens without breaking the surface truth of paint. The painting neither glorifies nor sentimentalizes coastal labor; it simply composes it with accuracy and affection. In doing so, Matisse shows how the most modest forms, rightly placed, can steady a horizon and carry the feeling of a world.