Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

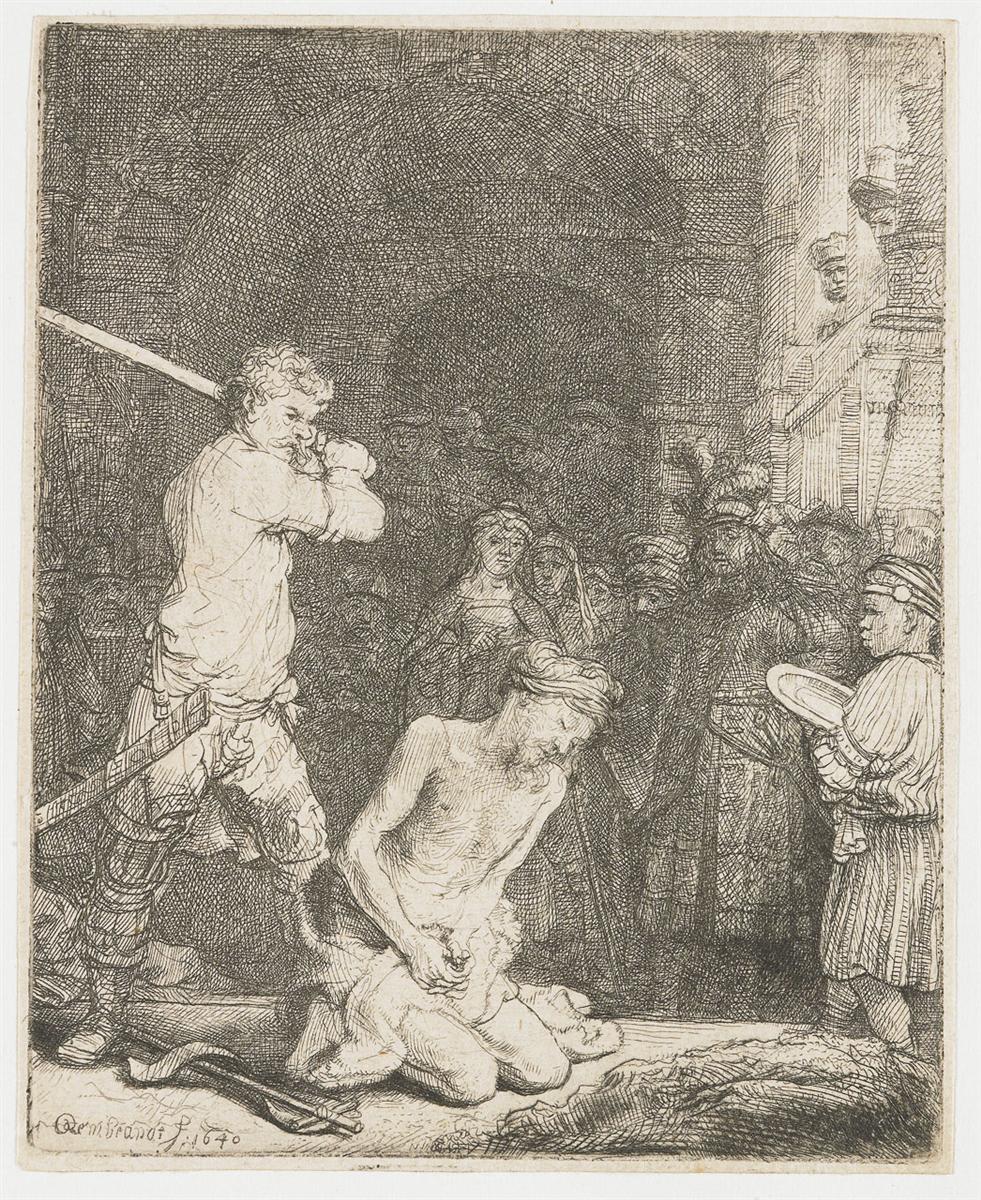

Rembrandt’s “The Beheading of John the Baptist” (1640) is a compact etching with the force of a stage tragedy. In a shallow architectural space, the executioner raises his sword; John kneels, body exhausted but dignified; a youth (often read as Salome’s attendant) waits at the right with a platter; soldiers, courtiers, and onlookers crowd the dim background. The first impression is not spectacle but pressure: the weight of the moment bears down from the massive arch overhead to the bare floor at our feet. With a web of lines—hatched, cross-hatched, and bitten at varying depths—Rembrandt converts copper into moral atmosphere, turning a biblical climax into an intimate confrontation with violence and witness.

The Biblical Subject and Its Human Core

John the Baptist’s beheading, ordered by Herod at the request of Salome and her mother Herodias, is among the New Testament’s most chilling episodes. Rather than emphasize the banquet with its decadence, Rembrandt focuses on the threshold between command and consequence, between life and execution. John’s body is the theological center. He is not a heroic nude; he is an old ascetic whose ribs, sinews, and limp skin tell of desert fasts and prophetic hunger. His hands meet at the waist in a gesture that reads as both bound and prayerful. In this etching, sainthood is carried not by halo but by an anatomy made truthful through line.

A Composition Built for Tension

The design arranges three principal masses: the executioner’s lifted arm and blade at left, John’s kneeling form in the center, and the attendant with the charger at right. These create a triad that encloses an invisible triangle of air above John’s head, a quiet zone that seems to throb with imminent movement. The crowd surges behind them like a dark tide, hemmed by monumental architecture that curves into a great arch. This arch is more than scenery: its heavy vault traps the event, compressing time and options. Rembrandt keeps the foreground bare except for John’s cloth and the executioner’s scabbard so that nothing distracts from the human calculus about to unfold.

Chiaroscuro Without Theatrics

Etching is a linear medium, yet Rembrandt can summon light and shadow with painterly subtlety. He thickens cross-hatching under the arch and deepens the bite within the crowd until that background becomes a velvet wall. Against it, John’s pale body and the sleeve of the attendant flare like islands of light. The executioner’s shirt gathers a milky tone that distinguishes him from the murk. This orchestrated contrast is not decorative. It directs attention: John’s luminous skin is the sanctified flesh of martyrdom; the attendant’s white dish anticipates the grisly trophy; the executioner is bathed in the cold illumination of duty. The scene is nightmarishly clear, but only where moral decisions burn hottest.

The Executioner as Reluctant Agent

Rembrandt refuses to make the executioner a caricature of cruelty. He is young, muscular, and intent; his jaw sets not with sadism but with the focus required to finish an ugly task. His sword is raised with both hands in a high arc, suggesting a blow meant to be decisive. The twisted strap at his thigh, the scabbard cast aside, and the slight forward pitch of his weight indicate motion already begun. He is a professional, and professionalism in the service of injustice is one of the etching’s most unsettling truths. The figure becomes a study of how violence can be ordinary.

John the Baptist as Vulnerable Authority

Kneeling and nearly nude, John is at once powerless and priestly. Rembrandt describes the shoulder blades, the loosened skin at the belly, the moving tendons at the neck with a tenderness that confers dignity. The head tilts downward, beard pointing toward the cloth that barely covers him; the mouth is parted as if mid-prayer or in final breath. There is no melodrama—only resignation that does not collapse into despair. The saint’s authority is moral rather than physical. In a crowd of armored bodies and feathered hats, it is his frail torso that receives the brightest light.

The Charger and the Chilling Courtesies of Court

At the right, a boy or page holds the charger upon which John’s head will be placed. Rembrandt renders the platter’s rim with an elegant ellipse, catching a soft highlight that echoes ceremonial silver. The child’s posture is stiff, eyes lowered, ritualistic; he is both innocent and implicated. This detail supplies the etching’s coldest insight: courts can package cruelty in the language of service. The platter, polished and proper, is the etiquette of atrocity.

Crowd Psychology and the Theater of Witness

Behind the primary actors, a dense audience gathers: soldiers with halberds, courtiers in plumes, women craning for a view. Their faces, etched with quick abbreviations, are not unique portraits but types of response—curiosity, detachment, impatience. Some peer from the shadows under the arch; others lean at the balcony on the right, participating from a safe remove. The crowd’s anonymity is strategic. By refusing detailed identities, Rembrandt converts them into a mirror for us. The moral question shifts from “What do those people feel?” to “What do we feel as witnesses caught between complicity and compassion?”

Architecture as Moral Weight

The setting evokes a grand, vaguely classical palace: heavy piers, a cavernous arch, carved grotesques jutting from the balcony. These forms are drawn with tight cross-hatching to emphasize mass. Architecture, here, is not neutral backdrop but instrument of power. The high arch suggests the state’s unyielding vault under which individual life is small. Yet this same architecture also frames the saint in a kind of apse, inadvertently sanctifying the execution with the geometry of a chapel. Rembrandt’s ambiguity bites: empire can consecrate its own violence.

The Line as Flesh, Cloth, and Air

Rembrandt’s mastery of the etched line turns copper into matter. Short, curved strokes on John’s torso read as creased skin; parallel hatching down the executioner’s sleeve suggests linen under strain; tiny burrs catch ink along contours, creating a velvet softness appropriate to flesh. The ground’s openness around the foreground figures lets air circulate between them and the viewer. Conversely, the packed mesh of the background transforms space into pressure. Nothing is casual. Every mark carries a tactile decision.

The Moment Chosen: Time Suspended

The plate captures the beat just before the sword falls, not the gruesome aftermath. This restraint is not squeamishness; it is a deliberate choice to implicate the viewer’s imagination. Suspense makes us complicit: we finish the action in our minds. By selecting the second before impact, Rembrandt keeps the scene ethically open. We are invited to consider not just the shock of violence but the human processes that lead to it—orders given, rituals prepared, bodies arranged.

Comparison with Earlier Depictions

Traditional treatments of the subject often emphasize the banquet, Salome’s dance, or the gruesome presentation of the head. Rembrandt redirects emphasis away from spectacle to the mechanics of power. Where Caravaggio’s versions dramatize the moment after decapitation with theatrical light and wide spaces, this etching crowds the scene into a press of bodies and stone. The difference is crucial: Rembrandt turns an event into a system—how courts operate, how duty dulls conscience, how crowds metabolize violence into entertainment. The result is less dramatic in a conventional sense yet more psychologically modern.

Plate Tone, States, and the Atmosphere of Ink

Many impressions of the etching show a veil of plate tone left on the copper during printing. That tone thickens the background and cradles the figures in breathable gray, strengthening the division between foreground light and architectural dark. Rembrandt was keenly sensitive to such effects, often varying wipe and pressure to tune the mood of each print. Even without color, he paints with ink on the press bed—richening shadows, warming paper whites, and adding a humid density to the air of the prison-court.

Gesture, Anatomy, and the Ethics of Realism

The figures are anatomically persuasive without academic display. The executioner’s stance, legs braced for the downward cut; John’s weight folded back onto his heels; the page’s careful grip on the platter—all speak a language of believable bodies. This realism intensifies the moral claim: sanctity and brutality occur in ordinary muscle and bone. Rembrandt refuses to let the scene drift into allegory. The truth of tendon and rib becomes a witness more trustworthy than emblem.

The Role of Women and the Absent Herod

Herod and the dancing Salome are not front and center; they are absorbed into the vague crowd or perhaps out of frame. This absence shifts focus from individual culpability to systemic action. The mother’s malice and the ruler’s cowardice are present as rumor rather than portrait, making the image harder to deflect as “their sin.” The etching asks us to consider how a culture arranges obedience so that wrong can proceed smoothly, with instruments ready and platters polished.

Viewer Position and the Ethics of Proximity

We stand almost beside John, close enough to see the wiry hair at his chest and the rough weave of the cloth at his knees. The executioner’s blade arcs partly toward us; the page’s charger is at our eye level. This proximity is ethically risky. The print disallows safe detachment. Our closeness becomes responsibility: we cannot pretend not to have seen. Rembrandt converts spectators into moral participants.

Symbolic Echoes Without Overstatement

Despite its realism, the etching whispers symbols. John’s bare body, aligned with the cloth spread on the ground, evokes sacrificial victims; the arch over his head resembles a church apse; the charger anticipates the Eucharistic paten with a blasphemous twist. Yet Rembrandt never nails down interpretation. He prefers resonance to allegorical captioning, leaving space for the viewer’s theological imagination to work.

The Soundless Roar of the Crowd

The print carries an acoustic imagination. The hatching that fills the background reads like a dense murmur—voices, clinks of armor, the scrape of the sword drawn free. Against this noise, John’s silence is palpable. The etching thereby creates a contrast between public clamor and private resolve. We feel how hard it is for a single conscience to stand within systems that cheer efficiency.

A Meditation on Power and Ritual

At its core, the image exposes a ritual of state violence: a command given behind the scenes; a body presented; an instrument raised; a dish prepared to catch the result; a crowd to certify the act. Rembrandt neither sensationalizes nor moralizes; he shows how ritual transforms horror into procedure. Seen in this light, the print becomes a meditation on all times when institutions convert dissent into ceremony, leaving only the witness of the vulnerable.

Lineage Within Rembrandt’s Oeuvre

Rembrandt returned often to the drama of martyrdom, execution, and suffering—“The Descent from the Cross,” “The Entombment,” “The Three Crosses.” This 1640 etching stands out for its worldly tone. It is less about miracle than about the machinery that grinds prophets. Its worldly intelligence anticipates his late prints, where massive darks and scoured whites push emotion to the brink. Here, the balance is ideal: controlled line, heavy atmosphere, and a human focus that never slips.

Why the Image Still Resonates

The etching speaks to modern viewers because it understands how violence is made ordinary—through roles, uniforms, architecture, and audience. It refuses cinematic gore, trusting the viewer’s conscience to supply what is missing. And it gives dignity to the one figure who loses everything. John is not a corpse but a person, and in those last seconds the light is his. That moral distribution of light remains one of Rembrandt’s greatest gifts.

Conclusion

“The Beheading of John the Baptist” compresses a gospel tragedy into a space no larger than a book page and, in doing so, opens a vast inquiry into power, conscience, and witness. With etching’s simplest tools—line direction, bite depth, plate tone—Rembrandt stages a moment of suspended time: the sword poised, the saint waiting, the platter ready, the crowd leaning in. Architecture presses down like a verdict; the foreground clears like a stage; light finds the human center. The print neither condemns with slogans nor seduces with gore. It shows, and its showing still indicts and consoles. In the space between blade and neck, Rembrandt holds up a mirror in which empires and onlookers—including us—must see themselves.