Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

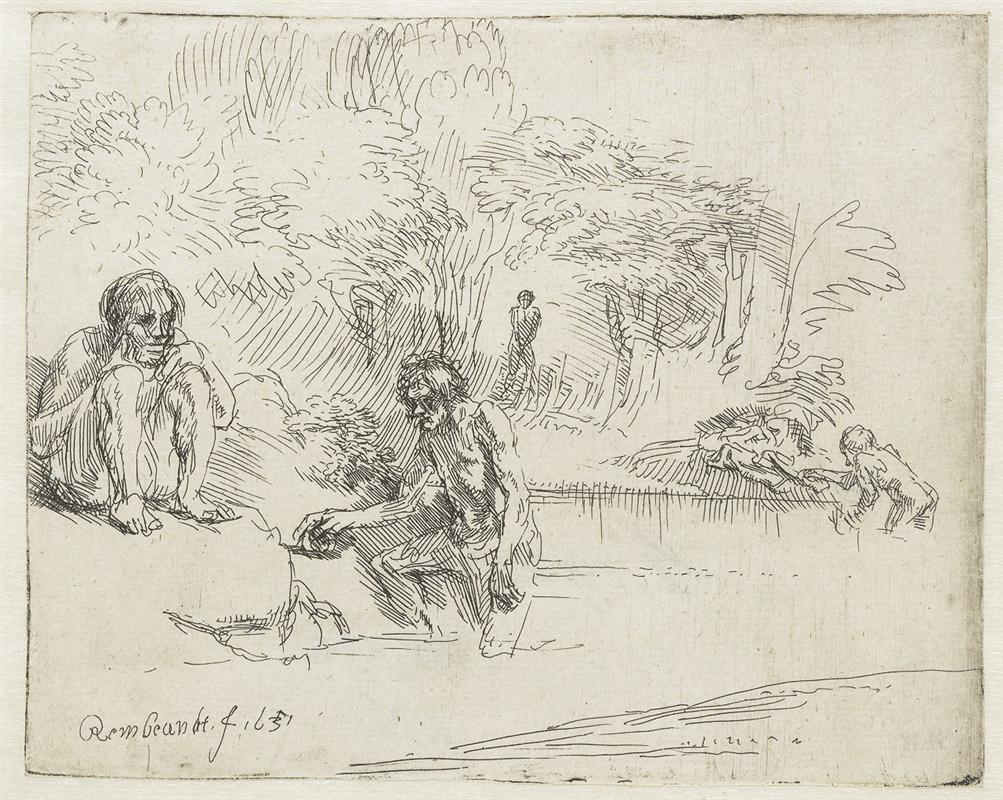

Rembrandt’s “The Bathers” is one of those deceptively simple sheets in which a few wiry lines conjure a whole summer afternoon. Several figures gather by a shallow stream beneath sheltering trees. One man crouches at the left bank, another kneels to trail a hand in the water, a third stands farther back in the wood, and, across the way, two more figures wade and recline. The scene feels unposed and provisional—as if we have stumbled upon ordinary bodies living in ordinary time. The subject is modest, yet the drawing-into-copper is so economical and alive that it becomes a quiet manifesto about what etching can do: sketch, think, and breathe.

Date, Context, And What The Plate Tells Us

The work is often listed under the year 1651 in modern catalogues of Rembrandt’s prints, a date that dovetails with his mature interest in naturalistic figure studies set outdoors. Yet many impressions, including the one reproduced here, carry the etched inscription “Rembrandt f. 1631.” That earlier year fits the linear calligraphy of the plate—the rapid contours, the small islands of cross-hatching, and the almost caricatural vigor of profiles. Whether we read the image as an early sermon on freedom of line or as a mid-century revisiting of an early copper, the point remains: Rembrandt is experimenting with the most direct, improvisatory uses of the needle to fuse figure study, landscape notation, and the play of water into a single sheet.

Subject And First Impressions

The eye lands first on the two large bathers in the foreground: one squats, chin on fist, toes gripped to the bank; the other kneels, torso twisting as he reaches to test the stream. Behind them, a standing figure lingers among trees, while at far right a pair of bathers—one reclining, one bending—completes the arc. Nothing is heroic, allegorical, or theatrical. These are men cooling off, washing, teasing the current, and resting in shade. The scene is built from tiny motions: a hand making ripples, a knee pressing into earth, a head turning to listen. In the absence of grand narrative, attention itself becomes the story.

Composition And The Geometry Of Ease

The composition reads like a shallow stage whose front edge is the waterline. Rembrandt arranges his figures in a loose semicircle around that edge so that the viewer moves from left to right—croucher, kneeler, stander, recumbent bather, wader—and back again in a lazy loop that echoes the stream’s flow. The mass of trees arches above like a leafy proscenium. Negative space does crucial work: the pool at center is left almost untouched by hatchings, a bright oval of quiet against which the figures stand out. The effect is equilibrium without stiffness, a spatial order that feels as spontaneous as it is calculated.

The Language Of Line

The sheet is a masterclass in linear economy. Rembrandt refuses dense modeling; instead he delivers bodies as inventions of contour, profile, and a few internal accents. Lines thicken and thin like spoken phrases—quick on the bicep, searching along a jaw, fluttering in the clumps of foliage. Short, broken hatchings near the water’s edge create a gentle shiver that reads instantly as reflection. The trees are described by fan-shaped sweeps and scalloped outlines, a shorthand that gives volume without weight. Because everything is so lightly indicated, the viewer’s eye supplies the rest, completing muscle, bark, and current from scraps.

Light, Air, And The Open Plate

Unlike Rembrandt’s later, darker etchings rich with plate tone, “The Bathers” lives in brightness. The copper appears wiped clean; shadows are things of line rather than tone. This openness carries the sensation of air—heat dispersed under leaves, light skipping across the stream. The emptiness around forms is not a lack; it is daytime itself. By withholding heavy darks, Rembrandt keeps the bodies buoyant, as if air were part of their anatomy.

The Body As Lived Form

Rembrandt’s bathers are not antique ideals. They are specific: narrow shoulders and sinewy thighs, slack bellies, ribcages that shift as torsos twist. The crouching man at left is compact and knotted; the kneeling figure is longer, his torso corkscrewing as he reaches down. Fingers splay, toes clutch, skin wrinkles at joints. The realism is affectionate rather than clinical—the bodies are observed with the same humanity Rembrandt gives to beggars, soldiers, and saints. Here, physical truth becomes a kind of moral truth: bodies are worthy of attention because they are the vessels of ordinary life.

Gesture, Posture, And The Psychology Of Ease

Every gesture is legible and quietly telling. The left-hand figure’s chin-on-fist pose suggests a break from labor and a drift into thought. The kneeler’s extended hand is both practical (testing temperature, rinsing dirt) and emblematic—a touch that binds human and element. The distant stander looks not at the water but into the trees, a sentinel or daydreamer anchoring the depth of the scene. On the far bank, one bather lounges with a languor that shifts the sheet’s tempo from alert to drowsy. These attitudes add up to a psychogram of rest: different ways the body says “enough” in summer shade.

Water As Actor

Water is the third protagonist after line and body. Rembrandt represents it with almost nothing—half a dozen strokes and a white reserve—and yet the stream feels palpable. It loops softly around the bank, it accepts the touch of a hand, and it takes the weight of a stepping foot at the right edge. By keeping the pool open and bright, he allows water to become a visual rest, a space that gathers the scattered sketches of movement into calm.

Landscape As Companion Rather Than Backdrop

The trees are drafted with speed but not carelessness. They swell and recede like green surf, their inward arcs enclosing the bathers in a natural room. Trunks are indicated sparingly, their verticals lost in bursts of foliage. The landscape does not compete for attention; it participates. The curved leaf-masses echo the curves of shoulders and knees, as if the place were tuned to receive the bodies it shelters. In a culture famous for its ordered polders and engineered horizons, this pocket of unmanaged shade feels intimate and humane.

The Freedom Of Etching As Drawing

One of the sheet’s pleasures is how frankly it shows process. You can feel the etching needle skate, hesitate, and bite again. Some lines are exploratory and left standing; others are emphatic. This candor turns the print into a thinking space. Rembrandt is not “finishing” an image; he is discovering it. That discovery is contagious: viewers recognize the signs of a hand searching in real time and are invited to complete the scene with their own looking.

Time Of Day And Seasonal Temperature

No sunbeam is drawn, yet the sheet breathes afternoon. The easy postures, the tree-canopy density, and the sense of unhurried drift read as high summer. The absence of wind—no flagged grasses, no hard diagonal hatchings—keeps the moment still. Piercing light and deep shadow are both avoided; instead we inhabit the mild brightness of shade near water, the kind of light in which a long hour can slide by uncounted.

Echoes Of Antiquity Without Imitation

Bathing scenes inevitably recall classical subjects—satyrs at a spring, nymphs surprised, river gods at rest. Rembrandt knows that lineage and sidesteps it. There is no mythology here, no heroic body, no intruding voyeur. If we sense antiquity, it is only in the timelessness of men by water. The sheet democratizes what ancient art reserves for gods by granting ordinary bodies access to the same sculptural clarity and compositional grace.

Sensory Imagination: Sound, Touch, And Temperature

The economy of line sparks other senses. One can hear the minute splash of fingers entering water, the creak of a knee as a croucher shifts, the small scuffle of a foot along the bank. One can feel warm bark, cool stream, powdery dry soil. Etching does not provide color, yet Rembrandt’s rhythms of line conjure sensory worlds: the sour-green smell of leaves, the mineral taste of a shallow brook, the slightly clammy feel of shade on skin.

Comparison With Other Rembrandt Bathers

Rembrandt returned to bathing figures throughout his career, perhaps most famously in the intimate “Bather” of 1654, where a lone man lifts his foot from water with wry self-awareness. Compared to that later, single-figure study, this earlier multi-figure print is more conversational and social. It reads less like a portrait of a particular body and more like a vignette of shared rest. Yet the two works share a refusal of idealization and a delight in awkward grace—the truth that bodies are lovelier when they belong to real people doing real things.

Humanism And The Everyday

The sheet’s ethics reside in its subject choice. To devote copper, acid, and ink to men cooling themselves at a brook is to assert that everyday intervals matter. The image honors maintenance of the self—washing, resting, pausing—as seriously as more public actions. In a culture of trade, war, and doctrinal debate, Rembrandt reserves space for simple ease. That stance is not escapist; it is restorative. The dignity of ordinary moments is one of his most consistent themes.

The Viewer’s Place On The Bank

Where do we stand? At the very edge of the stream, almost level with the kneeling figure’s hand. The composition places us inside the circle of ease, neither above the bathers nor intruding on them. The view is intimate yet respectful, as if we, too, have taken off our shoes and sat down. That positioning prevents the scene from becoming a spectacle; it makes it a shareable space.

The Plate As A Portable Landscape

A printed image turns a place into something you can fold, store, and carry. “The Bathers” would have circulated in portfolios, cabinets, and albums, available to be revisited in winter or in far-off rooms. Its portability matters. Rembrandt is not only representing leisure; he is manufacturing it—offering owners a pocket of shade and water they can enter with their eyes whenever they wish. The economy of line aligns with that function: the less ink insists, the more the viewer can breathe.

Humor And Warmth Without Caricature

There is a quiet humor in the crouching man’s tucked feet and the kneeler’s absorbed reach. Rembrandt often finds comedy in bodily truth—the way postures betray comfort, idleness, or intent. Yet he never tips into mockery. The smiles the sheet provokes are complicit, the smiles of someone who has been there: the scratch of grass against calf, the cool shock at the wrist, the slowing of breath under trees. The etching’s warmth is the warmth of recognition.

Technique As Meaning

Because the plate relies on contour and sparing hatch, its beauty is inseparable from its making. The visible decisions—the way a line trails off, the way two short strokes locate a knee—teach us how seeing works. Rembrandt trusts that if he places the right marks in the right relation, the world will appear, and that trust is contagious. Looking at the print, viewers learn to value suggestion over saturation, attention over accumulation. Technique becomes a lesson in perception.

Legacy And Continuing Appeal

“The Bathers” continues to attract because it feels contemporary in its minimal means and its affection for ordinary bodies. Artists and viewers who love drawing recognize in it a model: how to say more with less; how to let white space speak; how to anchor a composition with a handful of gestures. It also appeals to anyone who has sought relief by water. The sheet’s humanity—its refusal to turn bodies into symbols or sermons—keeps it fresh across centuries.

Conclusion

Whether we follow the inscription’s 1631 or the catalogue’s 1651, the essence of “The Bathers” is the same: an etching that turns line into leisure, bodies into lived forms, and a pocket of landscape into a state of mind. Few works demonstrate so clearly how Rembrandt could make copper breathe. The figures are ordinary, the place is ordinary, and that is the point. Out of ordinary acts—crouching, reaching, wading—he fashions an image expansive enough to hold time, weather, and the kindness of rest.