Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

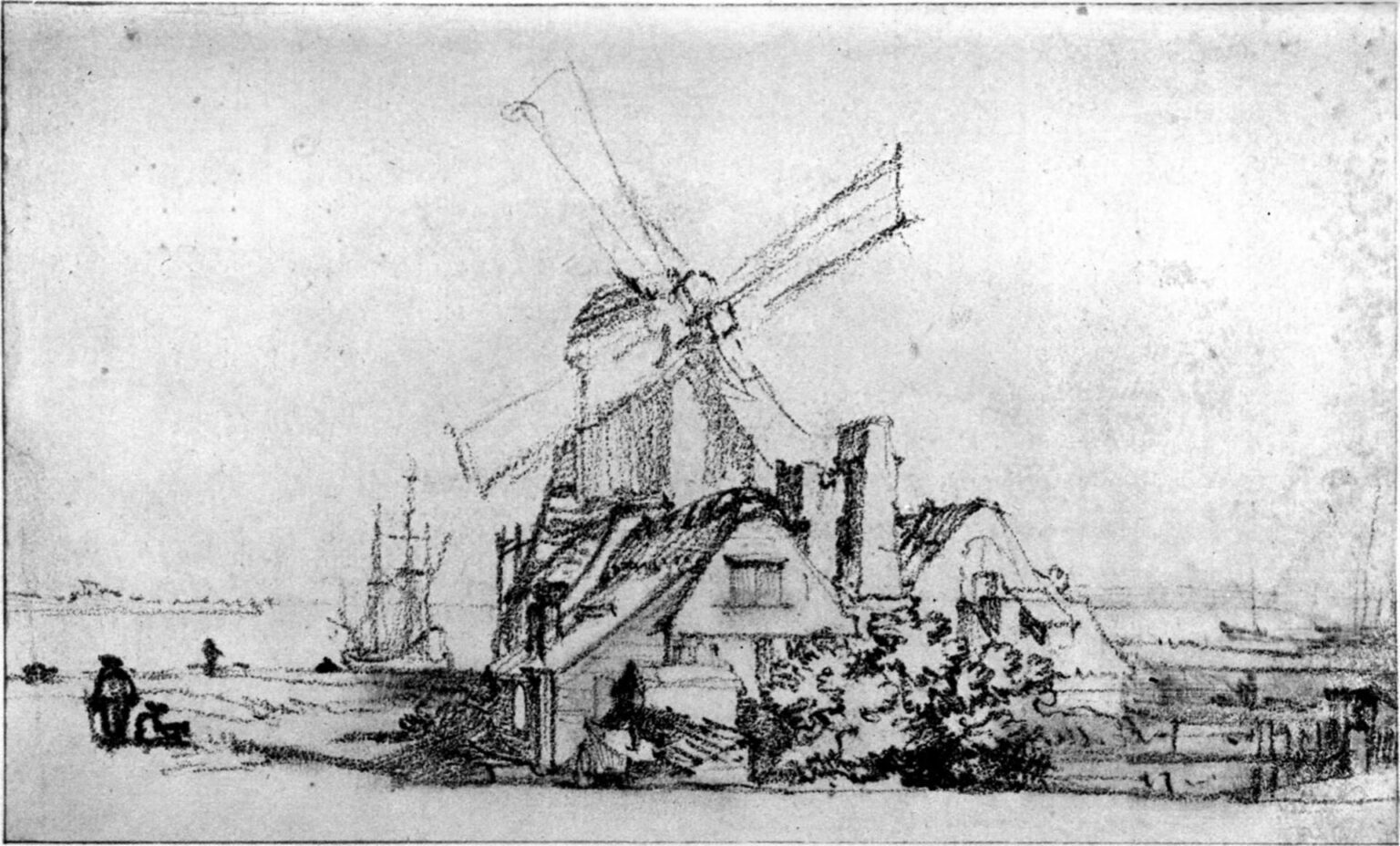

Rembrandt’s cityscapes are often overshadowed by his portraits and biblical scenes, yet they hold a quiet authority that reveals his sensitivity to lived space and civic identity. “The Bastion in Amsterdam,” dated around 1650, belongs to this intimate register. It is a compact landscape study that sets a windmill and humble houses against the waterline, with a few figures and ships mediating between land and harbor. The result is both a topographical memory of Amsterdam’s seventeenth-century defenses and a meditation on how daily life unfolds in the shadow of the monumental structures that safeguard a city. What makes the image compelling is not spectacle but tact: a selective orchestration of lines, tonal accents, and reserves of untouched paper that together summon an atmosphere of salt air, creaking timbers, and slow, routine movement.

Historical Setting And The Idea Of A Bastion

In Rembrandt’s Amsterdam, bastions were integral parts of the city’s fortifications—earthworks and brick-faced structures that projected outward in angled forms to control lines of fire and command approaches along water and land. They were engineering, architecture, and symbol all at once. For artists, they became motifs that bound together the civic and the natural: you could not represent the modern Dutch city without acknowledging the infrastructures that kept the sea out and enemies at bay. Rembrandt approaches the subject without theatricality. There is no triumphant parade, only the everyday architecture of security—a mill on a raised platform, domestic roofs huddled nearby, and, beyond them, traffic on the water. The bastion is present as an elevated, engineered ground and as an implied geometry that supports the mill, shaping the land into a purposeful edge.

Subject, Motif, And The Everyday City

The image organizes three kinds of human making: the house, the mill, and the ship. Each stands for a sphere of activity—dwelling, industry, and trade. The bastion grounds them, literally and figuratively, as the municipal framework that enables private life and commerce. Rembrandt’s choice to include a small figure with a dog at left, a few dark silhouettes near the water, and modest shrubs in the foreground underscores the ordinariness of the scene. This is the city experienced in passing, not staged for grandeur. The view suggests proximity to the city ramparts where life meets work: a place of paths, fences, mended roofs, and the watchful propulsion of sails.

Composition And The Geometry Of Stability

The composition pivots on a diagonal that runs from the low left foreground, along the line of the path and shoreline, up to the windmill’s axis. Against this, the horizontal sweep of the water acts as a stabilizing counterforce. The mill and chimneys puncture the horizon like anchor points, while the house roofs create a serrated rhythm that steps the eye upward toward the mill cap and sails. Rembrandt handles proportion with care: the mill’s sails are large enough to dominate the skyline but not so large as to become emblematic icons divorced from their setting. The image reads as a chain of linked volumes—low cottage, taller pitched roof, vertical chimney, and finally the cylindrical mill tower capped by a turning mechanism—so that the viewer senses a progressive ascent from domestic to civic scale.

Line, Touch, And The Economy Of Means

Although the drawing is sparse, the tactile variety is rich. Rembrandt uses swift, grainy strokes to suggest thatch and brush, short cross-hatchings for shaded eaves, and dense, crumbling blacks to anchor the doorway and the shadowed recess under the roofline. The mill’s sails are stated with confident, slightly irregular lines that feel informative rather than ornamental. A few darker accents—chimney, door, the figure at left—prevent the drawing from dissolving into mist, but he resists overworking any single passage. This economy of means is the engine of its presence: our eye fills in what the marks only hint at, and that collaboration between viewer and artist becomes the scene’s quiet drama.

Light And The Sugaring Of Atmosphere

Light in the drawing is not depicted through systematic modeling but through a distribution of brightness and restraint. The paper’s white is the air; the thin marks across the water’s surface modulate it just enough to imply sheen and distance. The roofs receive a wash of tone that reads as weathered material rather than theatrical illumination. Because the sky is left largely undisturbed, the sails and the mill cap float in a pale expanse that suggests breeze and moving cloud. The interplay of untouched paper and compressed black accents functions like breath: the scene exhales with space and inhales to hold the structural nodes.

Space, Distance, And The Scaffolding Of Perspective

Rembrandt does not rely on strict linear perspective to map the site. Instead, he combines overlapping forms, diminishing scale, and selective detail to produce spatial conviction. The boat at mid-distance is rendered with fewer strokes than the house but with enough specificity to read as rigging and masts. Beyond it, the rightmost shoreline tapers into a compressed register of marks that signals the far bank. The fence and hedge in the front register provide a tactile baseline, almost a tactile bar that the eye crosses to enter the picture. The result is a space that feels navigable, as though one could trace a path from the foreground figure to the dock, then around the house and up the ramp to the mill.

Human Presence And The Pulse Of Daily Life

The tiny figure walking a dog might seem merely anecdotal, yet it calibrates the entire scene. This human scale turns the mill and houses from anonymous masses into lived structures. The figure’s smallness also intensifies the bastion’s protective role: here is the citizen who benefits from a city that invests in defenses and harnesses wind for grinding grain, sawing timber, or pumping water. The ships echo that theme in a mercantile register. Even without a bustling crowd, the scene thrums with purposeful movement—the circular potential of the sails, the implied tack of boats, the directionality of paths and shorelines. Everything is about passage and exchange.

The Windmill As Symbol And Mechanism

In Dutch art, the mill is both literal machinery and cultural emblem. It represents mastery over environment and resourcefulness in transforming wind into labor. Rembrandt, who excelled at showing the ordinary as luminous, treats the mill not as a heroic monument but as a neighborly giant. Its sails are sketched with enough looseness to imply rotation, their slight asymmetries suggesting the wobble of real wood and canvas in real air. The mill’s position on the bastion heightens the sense of vigilance and utility; it is a lookout and a worker in one. By placing it amid cottages, he insists that civic infrastructure is an extension of domestic life rather than its spectacle.

Water, Horizon, And The Dutch Imagination

The waterline stretches like a margin between certainty and risk. In this image, the horizon is open, luminous, and thinly inscribed, but it carries the weight of Dutch experience with the sea. The ships signify routes of trade and vulnerability alike; their presence near the bastion binds defense to commerce. Rembrandt’s attenuated marks on the water create a delicate texture that hints at tide and traffic. The city is imagined as a choreography of edges—dikes, quays, bastions—where human design continually negotiates with natural force. The spare drawing makes that negotiation legible without melodrama.

Edges, Reserves, And The Poetics Of Omission

One of Rembrandt’s strengths is knowing what not to say. Here, omission frames meaning. The sky is left almost blank; the far bank is a veil; the foreground path is only lightly indicated. Because so much is withheld, the few dense areas become semantically charged: a door threshold, a chimney block, the tangle of foliage at right. The eye is coaxed into completing forms, and in doing so, the viewer becomes momentarily complicit in building the city. This participatory quality is the quiet poetry of the drawing and a hallmark of Rembrandt’s graphic art.

Working Process And The Intelligence Of The Hand

The drawing reads as done from life or from a vivid, recent memory, with corrections left in place. The mill’s sails show slight restatements, as though the artist searched for their best angle or recorded a small shift in wind. Such restatements are not errors; they are evidence of visual thinking—of the hand testing possibilities to capture the sensation of looking. The translation from observation to line is immediate enough that the viewer senses time in the drawing, not just space. The moment of making has been preserved alongside the scene depicted.

Place Within Rembrandt’s Oeuvre

Rembrandt’s landscapes and city views from the 1640s and 1650s frequently balance observational fidelity with expressive shorthand. In etchings like river scenes and drawings of mills near the city, he builds worlds out of sparse means and trusts the viewer’s capacity to infer. “The Bastion in Amsterdam” aligns with that approach. It is not an exhibition piece but a thinking sheet, a place where ideas of structure, air, and movement cohere. It also resonates with his broader interest in thresholds—between light and shadow, sacred and secular, private and public. Here, the threshold is civic: the line where home meets fortification, where street meets water.

Material Condition And The Beauty Of Wear

The drawing’s granular blacks and soft mid-tones suggest dry media worked with varying pressure. The occasional smudge and soft edge serve the subject, evoking weathered surfaces and the bloom of moisture near water. Even if the sheet has aged, that aging harmonizes with the image’s themes of exposed structures and durable work. Rembrandt’s surfaces seldom chase polish; they value the evidences of use. In a scene about working architecture, such material frankness feels just.

Reception, Misreadings, And The Quiet Sublime

Because the subject is modest, there is a risk of underestimating the work. The eye may pass over it quickly, mistaking brevity for slightness. Yet its quiet is strategic. The drawing offers a model of attention, training us to find significance in infrastructural forms that normally escape notice. The sublime here is not in mountain peaks or storms but in the mutual fit of human design and environment. The bastion’s low angles, the mill’s revolving plane, the water’s patient horizontal—together they articulate an order that is protective without being oppressive, useful yet graceful.

What The Image Tells Us About Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam

The seventeenth century in Amsterdam was a period of civic investment and mercantile expansion. The city expanded its ring of fortifications, developed harbor facilities, and built the institutions that made trade possible at scale. The drawing registers that world indirectly, by attending to the edges where policy touches ground. We glimpse a society that takes seriously the business of maintenance: roofs patched, paths worn, hedges trimmed, sails mended. The mill is infrastructure, but also community; it is where grain becomes bread and where neighbors meet. By presenting this system in miniature, Rembrandt captures the ethical core of the Dutch urban project—pragmatic, collective, and attentive to place.

Why The Drawing Feels Contemporary

Modern viewers live with their own networks of unseen systems—levees, power grids, transit lines, logistics corridors. Rembrandt’s image returns those systems to visibility by showing a historical precursor with empathy and elegance. The drawing invites us to look at our cities and ask where the bastions are now, who maintains them, and how they shape our daily routines. Its pared-down style also anticipates the contemporary taste for minimal means and open space. The sheet is as much about air and intervals as it is about objects; it trusts the viewer to complete what is implied.

A Close Reading Of Key Passages

The cluster of roofs at center-right is described with broken strokes that catch at different textures—thatch, timber, and masonry. Their irregular patterning keeps the ensemble lively, resisting the monotony that can afflict rows of buildings. The chimney, a blunt vertical, acts as a hinge between house and mill. Below, a darkened doorway opens into an interior we cannot see, a reminder that the city is full of rooms, trades, and conversations that remain offstage. On the left, the small boat and its rigging create a counterweight to the mill’s sails; both are machines of wind, but one travels while the other is rooted. The figure with dog is an index of scale and a narrative spring, drawing us into the path’s gentle curve.

Memory, Observation, And The Ethics Of Looking

Whether executed on site or from recollection, the drawing models a way of seeing that is patient and generous. Rembrandt does not caricature the city or idealize it; he attends to the forms that make it livable and legible. This ethical stance—seeing what supports life and giving it form without spectacle—aligns with his broader practice in portraiture and religious scenes, where dignity often resides in the worn face, the tired hand, or the dim interior. In the bastion view, dignity belongs to the infrastructure and the people who inhabit it lightly.

Conclusion

“The Bastion in Amsterdam” distills a civic worldview into a handful of strokes. It locates beauty in useful things and ties human scale to municipal form. The drawing’s magic lies in its restraint: the more it leaves unsaid, the more capacious it becomes, inviting the viewer to breathe its air and walk its paths. As a record of Amsterdam’s defensive architecture, it is informative; as an image of ordinary life calibrated by wind and water, it is moving. Rembrandt’s genius here is to show that the life of a great city is not only in its market squares and churches but also in the unassuming places where walls meet docks, where mills turn against a pale sky, and where a passerby and his dog become the measure of all the surrounding forms.