Image source: wikiart.org

Overview of The Baptism of Christ

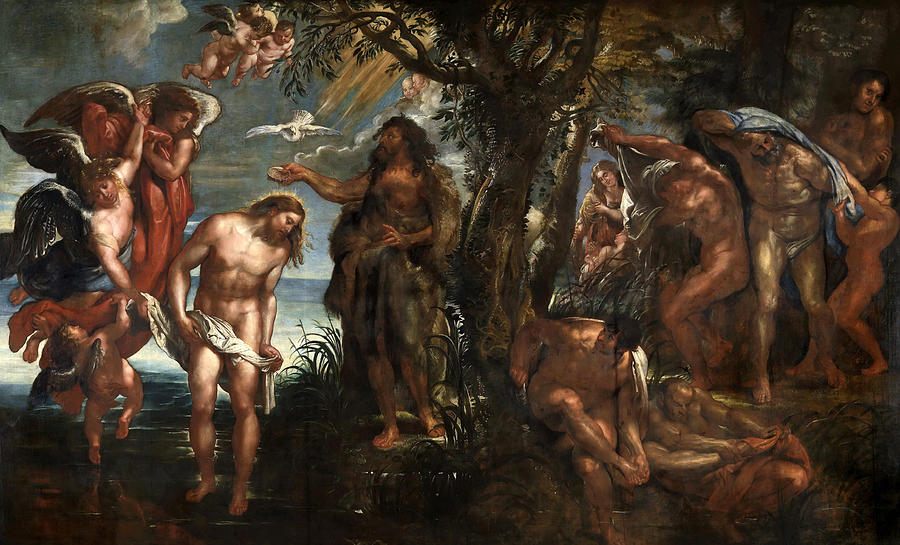

“The Baptism of Christ” by Peter Paul Rubens is a sweeping, energetic vision of the Gospel moment when Jesus enters the Jordan and is revealed as the beloved Son of God. Rather than isolate the central figures, Rubens surrounds the scene with angels and bystanders, turning the sacramental event into a grand Baroque spectacle filled with motion, light, and deeply human responses.

On the left, Christ steps out of the water, his body still gleaming with moisture, while angels rush forward with white draperies. Above, cherubs descend and a dove hovers in a ray of golden light, signifying the Holy Spirit. At the center, John the Baptist stands on the riverbank, his rough garment and commanding gesture marking him as prophet and forerunner. To the right, a cluster of muscular men and youths undress, wash, and prepare for baptism, visually linking Christ’s unique mission to the transformation offered to all believers.

The painting immerses the viewer in a landscape that feels both earthly and supernatural, a riverside grove where heaven breaks through the canopy of trees. Rubens’s dynamic composition, glowing color, and expressive anatomy together make this one of the most dramatic interpretations of the baptism theme in Baroque art.

Biblical Background and Theological Meaning

The painting interprets the account found in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Jesus comes to the Jordan River, where John the Baptist is preaching repentance and baptizing crowds. As Jesus is baptized, the heavens open, the Holy Spirit descends in the form of a dove, and a voice from heaven declares, “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.”

In Christian theology, this event marks the beginning of Christ’s public ministry and reveals the mystery of the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit united in one moment of manifestation. Baptism becomes not only a symbolic washing but an entrance into this divine life. Rubens captures these layers of meaning by juxtaposing Christ’s humble posture with the outpouring of heavenly light and the presence of other seekers at the riverbank.

The painting shows that Christ submits to a baptism of repentance he does not need, thereby sanctifying the waters for others. At the same time, the men on the right, washing and preparing, signify the people who will follow him into the waters of new birth. The scene presents both a unique, unrepeatable revelation and a pattern for every Christian’s spiritual journey.

Overall Composition and Spatial Drama

Rubens organizes the composition in three interconnected zones: the left with Christ and the angels, the center with John the Baptist and the descending Spirit, and the right with the group of catechumens and onlookers. A large tree stands near the middle, its trunk and branches separating yet linking the episodes, like a living axis around which the drama unfolds.

The eye moves first to the bright figure of Christ, whose pale body stands out against the darker water and foliage. From him, we follow the vertical beam of golden light up to the dove and cherubs, then down again along John’s gesturing arm. The Baptist’s rough, vertical form provides a strong counterpoint to Christ’s gentle curve as he bends slightly in humility.

To the right, the figures are more compressed and shadowed. Their twisting poses create a swirl of movement that contrasts with the more solemn stillness of Christ and John. Yet lines of gesture and gaze connect them: one man looks toward the central event, another bends in the water, while others pull off garments or wring out wet cloth. This orchestrated movement spreads the meaning of the baptism out into the wider human crowd.

The background landscape unifies everything. On the left, open sky and distant water create a sense of freedom and divine openness; on the right, trees and undergrowth close in, emphasizing the earthbound struggle of those still preparing for grace. Rubens thus uses space itself to symbolize the passage from old life to new.

The Figure of Christ: Humility and Radiance

Christ stands at the threshold between water and land, a position that captures his mediating role between heaven and earth. His head is slightly bowed, eyes lowered in prayerful recollection of the Father’s voice. Yet his body, bathed in soft light, radiates a quiet majesty.

Rubens paints him with a robust, athletic build typical of his heroic male figures, but avoids any sense of arrogance. The shoulders are relaxed, the arms hanging naturally as angels approach with a towel. The wet skin glistens, modeled with delicate transitions of warm and cool tones that suggest both physical reality and spiritual luminosity.

A simple white cloth at his waist underscores his purity and humility. Unlike the crowded, twisting figures on the right, Christ’s pose is calm and centered. He is the still point around which the entire composition moves. This balance between physical strength and gentle submission embodies the theological idea that true power is exercised in obedience to the Father’s will.

John the Baptist: Prophet at the Threshold

John the Baptist occupies the central ground of the painting, both literally and symbolically. Clad in his traditional camel-hair garment, with bare legs and wild hair, he appears as a rugged figure of the wilderness. His feet anchor him firmly to the bank as he extends one arm toward Christ, the other hand pressed modestly to his chest.

This gesture can be read in several ways. It recalls the act of pouring water, even though Rubens chooses not to show a literal stream falling onto Christ’s head. It also evokes the moment when John recognizes Jesus as the Lamb of God and insists that he is unworthy to baptize him. The combination of outward pointing and inward hand suggests that John both indicates the Messiah to others and acknowledges his own smallness before him.

Rubens paints John with strong, earthy tones—browns, russets, and tanned skin—that tie him to the rugged landscape. Yet the same divine light that touches Christ also glances off John’s shoulders and face, signifying his role as chosen herald. Standing between Christ and the crowd, he acts as bridge: the final prophet of the Old Covenant and the first witness of the New.

Angels, Cherubs, and the Descent of the Spirit

On the left side, a lively cluster of angels and cherubs breaks through the sky, filling the air with movement. Some bear white draperies for Christ, others look on in reverent joy. Their garments are painted in vibrant reds and soft blues, with wings that catch the light in feathery streaks.

Above them, rays of golden light pour down from an unseen source, converging on the white dove of the Holy Spirit. This dove hovers just above Christ’s head, wings spread, echoing the shape of the angels’ wings and tying heaven and earth together. The use of a bright, diagonal beam of light is typical of Baroque art and here emphasizes the moment of divine affirmation: the Father’s voice, though not visible, is suggested by the visual “voice” of the light itself.

The angels add not only theological meaning but emotional tone. Their excited, almost playful movement contrasts with Christ’s calm demeanor, showing heaven’s joy at the revelation of the Son. They also help lead the viewer’s eye downward and inward, from the celestial realm to the human drama at the water’s edge.

The Catechumens and Onlookers: Humanity Responding

The figures on the right side of the painting represent the men and youths who have come to John for baptism. Rubens turns this group into a study of varied human reactions to the call to repentance and renewal.

One man stands high on the bank, twisting his muscular torso as he pulls a blue garment over his shoulder. His pose suggests both modesty and readiness to step forward. Below him, another man bends to gather his clothes, while yet another kneels, washing his feet or legs in the water. At the very bottom, a figure reclines almost languidly, still half in the shadows, as if reluctant to rise and respond.

Farther back, partially hidden among the trees, more figures emerge, watching or preparing. Some seem eager, others hesitant. Collectively, they form a visual commentary on the human condition: people at different stages of awareness and willingness as grace approaches.

Rubens renders these bodies with his characteristic vigor: powerful limbs, twisting torsos, and complex interlocking poses. Their more earthy, shadowed tones contrast with Christ’s luminous flesh, highlighting the gap that baptism will bridge. They are not yet transfigured, but they are drawn toward the light emanating from the central event.

Landscape, Water, and Symbolism

The Jordan River setting allows Rubens to explore the symbolic potential of water and landscape. In the left half of the painting, the river is calm and reflective, its surface touched by light. The distant horizon and blue sky suggest openness and the promise of a new world beyond.

In the central and right portions, reeds, grasses, and thick foliage grow along the bank. The tree in the middle, with its rough trunk and branching canopy, can be read as a sign of life and rootedness. It also evokes the idea of the tree of life or the cross to come, standing silently at this early moment in Christ’s mission.

Water, of course, is the central symbol. It washes around Christ’s feet, clings to the bodies of those bathing, and fills the space between bank and horizon. In Christian imagery, water is both a sign of death—drowning, chaos—and new birth. By stepping into it, Christ anticipates his own death and resurrection; by emerging from it, he inaugurates a new creation. Rubens paints the water with subtle shifts of green, blue, and brown, making it a living element that connects all the figures.

Color, Light, and Rubens’s Baroque Style

Rubens’s color palette in “The Baptism of Christ” is rich and varied. Warm flesh tones dominate the figures, offset by the cool blues of sky and water and the deep greens and browns of the wooded bank. Strategic bursts of red—in the garments of the angels and in some of the draperies—inject energy and direct attention.

Light is handled in a characteristically Baroque way. It is not evenly distributed but concentrated in key areas: Christ’s body, John’s face and upper torso, the cluster of angels, and selected figures on the right. Shafts of supernatural light stream through the upper atmosphere, while softer reflections play on water and skin. This interplay of bright highlights and deep shadows gives the scene a sense of immediacy and three-dimensional depth.

Rubens’s brushwork is lively and confident. In the distant landscape and background foliage, strokes are loose and suggestive; in the main figures, they are more controlled, modeling muscles and features with care. The combination creates a sense that the scene is both solid and in motion, a moment caught in the middle of unfolding action.

Relationship to Rubens’s Other Religious Works

“The Baptism of Christ” fits into Rubens’s broader output as a master of large-scale religious narratives. Like his altarpieces of the Crucifixion, the Raising of the Cross, or the Descent from the Cross, this painting combines theological depth with dramatic staging and muscular anatomy.

Rubens frequently depicted pivotal moments in Christ’s life—Nativity, Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension. The Baptism is one of these decisive turning points, and he treats it with corresponding grandeur. The inclusion of robust nude figures recalls his interest in classical antiquity, while the expressive faces and gestures show his commitment to capturing human emotion in sacred history.

The painting also reveals Rubens’s ability to integrate multiple episodes into a single coherent composition. The baptism itself, the descent of the Spirit, the preparation of other penitents, and the heavenly rejoicing all coexist without confusion. This narrative richness is a hallmark of his mature style and contributes to the painting’s enduring appeal.

Emotional and Spiritual Impact

Beyond its technical brilliance, “The Baptism of Christ” carries a strong emotional and spiritual charge. The viewer senses both the quiet solemnity of Christ’s submission and the excited stir of heaven and earth around him. The angels’ movement, the men’s preparations, and the shimmering water create an atmosphere of expectancy, as if the whole creation is holding its breath while the Son of God steps into the Jordan.

The painting invites contemplation on personal identity and transformation. Christ, sinless yet willing to stand among sinners, becomes the model of solidarity and humility. The men on the right challenge viewers to see themselves among those in need of cleansing and change. The descent of the Spirit reminds believers that baptism is not merely symbolic but a real participation in divine life.

Rubens does not present these ideas in dry, didactic form. Instead, he lets color, light, and movement carry the message. Standing before the painting, one feels drawn into the scene, almost able to feel the cool water, hear the rustling reeds, and sense the warmth of the descending light. It is this immersive quality that makes the work such a powerful visual meditation on one of the central mysteries of the Christian faith.