Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

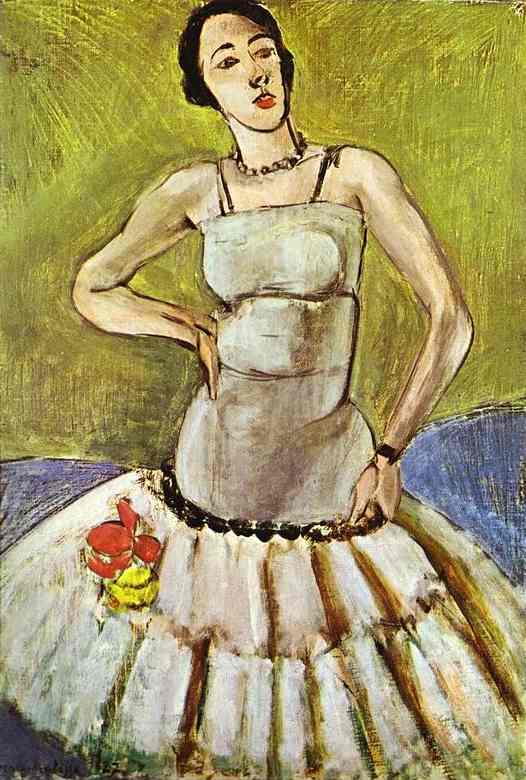

Henri Matisse’s “The Ballet Dancer, Harmony in Grey” (1927) captures a poised figure poised between motion and stillness, framed by an interior distilled to a few radiant planes. The tutu erupts like a halo from the lower edge, the bodice is rendered in sober greys, and the arms open in a declarative V that stabilizes the composition while hinting at choreography. Behind the dancer, a field of olive green rises like spring air; a partial band of ultramarine arcs along the horizon and slips beneath the white tulle. At the dancer’s hip, a small cluster of red and yellow rosettes adds a compact burst of warmth. Matisse reduces the stage to essentials so that color, contour, and rhythm can do the expressive work usually assigned to narrative. The canvas is not a backstage anecdote but a statement about modern harmony—how a limited key of greys, whites, and greens can house energy, grace, and clarity.

The Nice Period And The Discipline Of Decorative Space

Painted in the high years of Matisse’s Nice period, the picture demonstrates how the artist turned the Mediterranean studio into a testing ground for lucid color relations. Instead of deep perspectival rooms, he favored shallow stages made from curtain-like planes, patterned floors, or simple bands of color. In this work, the background is deliberately simplified. The upper field of olive green behaves like a cloth screen; the lower band of ultramarine functions as a low horizon; the black belt at the waist acts as an interior anchor. Such economy is not minimalism; it is discipline. It allows the figure to occupy the center with dignity while giving the eye stable intervals to measure. Decoration isn’t piled on. It is condensed into a grammar that paces looking.

Composition As A Theater Of Armature And Halo

The composition is engineered from a handful of decisive shapes. The tutu reads as a half-disc whose scalloped edge breaks the boundary between figure and field. The torso is a cylindrical tower set on that disc, and the arms radiate from the waist like counter-braces. The right hand perches at the hip with a rehearsal crispness; the left hand rests closer to the skirt, as if feeling the pull of the fabric’s weight. The neck column rises to a slightly tilted head that regards space with cool attention. This armature recalls the scaffolding of dance training: balance first, gesture second. Around it, the tutu’s halo supplies a luminous counterweight, translating kinetic potential into light.

Grey As Key, Climate, And Character

Calling the painting a harmony in grey announces the experiment. Grey, usually a mediator, is here the protagonist. Matisse organizes an entire range—from warm pigeon-grey to cool slate—across bodice, sleeves, and shadowed facets of the tutu. These greys have temperature and grain. Where the bodice rounds under the breastbone, the cool slate warms; where a sleeve turns toward the ultramarine band, a whisper of blue sneaks in; where the arm flexes and light thins, the grey goes chalky and airy. Nothing is dull. The greys absorb and redisperse surrounding hues, behaving like the dancer herself—calm, responsive, central. By building character through a restrained scale, Matisse proves that serenity is not the absence of intensity but its most rigorous form.

The Tutu As Sculptural Light

The tutu is painted with short, directional strokes that radiate from the waist and break into scallops at the edge. These strokes carry two kinds of information at once: the structural ribs of tulle and the way light courses over them. The white is never a single note. It slips toward bone where the fabric thickens, takes on lavender when it meets the ultramarine band, and warms to cream where it catches the olive of the backdrop. The black beaded belt and the little rosettes at the hip translate the tutu’s brightness into rhythm, keeping the lower half from evaporating. The result is a ring of light that also reads as mass—an elegant contradiction aligned with dance itself.

The Background Bands And The Ethics Of Flatness

Behind the figure, two large planes carry most of the spatial information. The olive field is brushed thinly so undercolor breathes, creating a feathery halo around the head and shoulders. The ultramarine band is denser and cooler; it presses forward where it meets the tutu, flattening the stage and forcing figure and ground to negotiate at a crisp edge. This productive flatness is a hallmark of the Nice interiors. Depth is implied through overlap—the skirt over the blue, the arms over the bodice, the head projecting into the green—but perspective is otherwise withheld. The eye attends to surface relations, the site where meaning is made in Matisse’s practice.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Line

The figure’s authority comes from contour. Matisse lays the jaw with a single, sure curve that tightens near the ear and slackens toward the chin. The shoulders are carved by vigorous strokes that change pressure, acknowledging bone and muscle without anatomical chatter. The straps of the bodice are unfussy bands that settle the head onto the torso. The hands are abbreviated to essential angles and pads, with a few crisp highlights to convince the eye. The edges of the tutu remain lively, never mechanical; they flutter where a scallop catches light and settle where a fold thickens. Such breathing lines contain color while letting it breathe—an economy that keeps the picture graphic and sensuous at once.

Ornaments As Structural Notes

Every ornament in the painting is earned. The black beaded belt does triple duty: it anchors the waist, supplies a measured tempo between torso and tutu, and echoes the dark accents in hair and lashes. The small rosettes at the hip—one red, one yellow—are not cute details; they are compact temperature shifts that summarize the painting’s warm-cool dialogue. The pearl necklace is a quiet ostinato around the throat, repeating the rhythm of the belt at a lighter pitch. These punctual notes keep the harmony from dissolving into broad fields; they articulate transitions and give the viewer footholds for attention.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

Light in the Nice studios tends to be ambient, and Matisse respects that diffusion here. Shadows are chromatic rather than black; they slip toward olive on the upper arms, toward blue on the skirt’s underplane, toward mauve at the base of the neck. Highlights are dispersed and precise: a milky dot on a pearl, a pale ridge on the wrist bone, a small cool flare on the cheek. Because the value range is moderate, color assumes the modeling burden. The dancer’s solidity is not the result of heavy contrast but of chromatic negotiation from plane to plane.

Gesture And The Memory Of Movement

The stance—hips squared, one hand at the waist, the other skating the top of the skirt—comes from the disciplined vocabulary of rehearsal. The arms open like parentheses, inviting the torso to breathe; the head tilts with a refinement that feels learned rather than improvised. Although the legs are invisible, the posture implies them. The torso’s slight torque suggests turnout; the lifted chest forecasts balance on demi-pointe. The painting captures a pause within choreography, where the body gathers itself for the next phrase. Stillness becomes a repository of motion.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse often described painting as akin to music, and this canvas is a chamber piece in a restrained key. The olive field sustains a long, soft chord; the ultramarine band holds a cooler pedal beneath it; the beaded belt ticks like a metronome; the pearl necklace plays the same beat on a lighter instrument. The eye traces a recurring melody: face to pearls to strap to belt to rosettes to scallops of the skirt and back up the other arm to the chin’s curve. On each circuit, small harmonies reveal themselves—a grey on the bodice borrowing blue from the band, a warm highlight on the forearm answering the red rosette, a feathery brushmark in the green echoing a frayed edge of tulle. The score is simple to read and rich to replay.

Space, Depth, And The Conviction Of Shallow Stages

The space is shallow by design. The dancer stands near the picture plane; the background behaves like hung cloth instead of distant architecture. Overlaps do the persuasive work: the tutu in front of the blue, the torso casting a cooled reflection into the skirt’s upper folds, the arm defining the ribcage by simply crossing it. This shallow stage does not impoverish the image; it clarifies purpose. When depth is compressed, relations among colors and edges become vivid, and the viewer’s attention stays with the things Matisse can control precisely—the spacing of intervals and the balance of temperatures.

The Modernity Of Restraint

Many Nice-period interiors burst with pattern and objects, but this ballet image proves that Matisse’s modernity did not depend on abundance. Here he tests how much can be removed while still delivering fullness. A limited palette, a small roster of shapes, and a few decisive ornaments do all the work. The painting feels contemporary not because it copies the fashions of its moment but because it wagers on clarity. It argues that the decorative is not frill but method—that a sequence of tuned planes can carry as much feeling as a crowded narrative.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“The Ballet Dancer, Harmony in Grey” converses with Matisse’s other dancer images from 1927. Compared to the version with rose tights and poster-like color bands, the present work leans into sobriety, allowing grey to lead while green and blue act as atmosphere. It also speaks to the seated ballerina on a stool from the same year: both deploy a ring of tulle as architectural center and use a single diagonal or armature to pace the whole. The grey harmony further forecasts the serenity of the late paper cut-outs, in which large shapes meet at clear edges and color fields hold the image’s logic without heavy modeling.

Tactile Intelligence And The Reality Of Paint

The material presence of paint matters. In the green field, scumbled strokes let the weave of canvas contribute a fine tooth, so air feels textured. In the ultramarine band, more saturated passes create a smooth, cool reservoir that sets off the tutu’s dry, feathery impasto. On the bodice, Matisse alternates thin glazes and creamy touches to suggest the give of fabric over bone. Hands and face receive denser, more deliberate notes—small scrapes and backed-off edges that keep them from hardening into caricature. This choreography of touch persuades without incantation: each surface feels specific while remaining loyal to the flatness that carries the composition.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

The dancer’s expression is poised, inward, and alert. The slight tilt of the head suggests evaluation more than seduction—perhaps the quiet inventory a dancer conducts at the studio mirror. The space participates in this psychology. The olive field calms without dulling; the ultramarine steadies; the disciplined greys keep rhetorical heat in check. For the viewer, the experience is neither spectacle nor puzzle. It is a gradual settling into a climate where attention can linger. The longer you look, the more modest correspondences accumulate, building a persuasive sense of rightness.

Evidence Of Process And The Earned Harmony

Close looking reveals pentimenti and adjustments that make the serenity credible. A strap has been restated to align with the shoulder’s turn; a scallop of tulle has been moved to better sync with the belt’s cadence; a contour along the left forearm shows light abrasion where an earlier line was softened. These traces are not blemishes. They are the record of tuning—how Matisse tested intervals until the harmony in grey truly felt harmonic.

Why The Painting Endures

The work endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Return to it and a new hinge appears: a grey in the bodice catching green from the field; a pale violet tucked into a tutu shadow that answers the ultramarine; a pearl glint that aligns with a highlight on the wrist; a rosette’s red that reappears as warmth along the lower lip. None of these observations consumes the image. They refresh it. The painting supports daily looking—the ultimate criterion for decorative art with intellectual ambition.

Conclusion

“The Ballet Dancer, Harmony in Grey” confirms Matisse’s belief that clarity is a kind of generosity. With a limited palette led by greys, a few emphatic planes, and a balanced pose, he composes a room in which color acts as architecture, contour as breath, and pattern as measured rhythm. The dancer is not narrative decoration but the central interval around which the whole stage finds equilibrium. The picture is serene without blandness, disciplined without austerity, and modern without noise. It invites viewers to slow down, trace the intervals, and recognize how much feeling can be carried by the simplest means when they are tuned with care.