Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

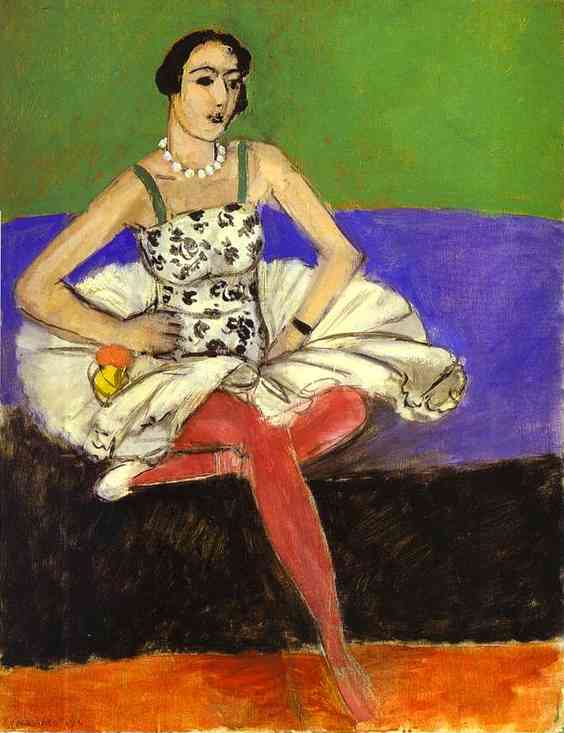

Henri Matisse’s “The Ballet Dancer” (1927) is a taut, luminous statement about how color, contour, and pose can convert a simple studio scene into a modern emblem. A ballerina sits frontally on a low ledge, her white tutu flaring like a crisp halo against a banded backdrop of green, ultramarine, and black. A string of pearls fixes the tempo at the neckline; a patterned bodice flickers with dark motifs; rose-red tights drive a single diagonal through the whole stage. The painting is less a portrait of a particular dancer than a demonstration of how a figure can anchor a shallow, decorative architecture, how large planes can be tuned like chords, and how stillness can carry the memory of movement.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Stage

By 1927 Matisse had refined the language of his Nice interiors into a classicism of intervals. The Riviera’s steady light allowed him to shift from Fauvist shock to long, breathable harmonies. Interiors became portable theaters: a few colored backdrops, a ledge or stool, a scattering of props, and a model who could sustain a pose that read like a sentence. In this work the stage is reduced to essentials. A wide green field, a saturated strip of ultramarine, a grounding bar of black, and a warm red floor supply the entire architecture. The dancer brings the room to life, but the room, with its deliberate planes, grants the dancer modern clarity.

Composition As A Poster-Like Score

The composition reads at a glance and rewards long looking. The tutu forms a central disc whose scalloped edge breaks the hard bands behind it, keeping the surface alive. The torso and head rise as a compact tower above the disc; the arms open outward to settle the mass, one hand set in the waist, the other lifted in a tiny prelude to motion. The right leg crosses under the tutu in a bent triangle, while the left leg shoots diagonally downward, touching the floor in a graceful point. Three large horizontals carve the background and stabilize the figure’s thrust. The result is a poster-like clarity that remains elastic enough for nuance.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

Color does the structural work. The top field is a springlike green, bright but slightly softened by scumbled strokes; it sets a fresh climate around the head and shoulders. The middle band of ultramarine cools the stage and throws the tutu forward; its density keeps the white disc from dissolving into background glare. The black bar beneath it is a necessary weight, a rest in the musical sense, against which the rose-red tights can sing without shrillness. The floor’s orange-red warms the lower register and returns warmth to the face and bodice. The dancer’s costume binds the palette. The bodice’s black floral motifs repeat the black bar behind; the white tutu and pearls rhyme with the green’s paler tints; the red tights collect the scattered warm accents into a single, decisive diagonal.

The Tutu As Sculptural Ring

Matisse paints the tutu with disciplined economy. Short, loaded strokes radiate from the waist and break into slightly frayed scallops at the rim, so tulle reads as both airy and structural. Where the tutu overlaps the ultramarine, whites cool toward blue; where it crosses the green, they warm; where it turns over the black band, the edge bristles with crisp contrast. The tutu is more than costume. It is the painting’s ring, a sculptural device that compresses space and gathers the dancer’s energy into a single revolving form.

Costume, Ornament, And The Grammar Of Pattern

The patterned bodice is a study in how ornament can clarify rather than distract. Its small dark motifs are spaced like notes on a staff and echo the black band behind, welding figure to field. Green straps pick up the top register and tether the torso to the background plane. A pale necklace, bead by bead, gives the head a measured halo and repeats the tutu’s rhythm at smaller scale. A yellow-orange pompon near the hip adds a tiny sun that bridges warm floor to cool midsection, keeping the color chord from splitting into separate halves.

Pose, Gesture, And The Memory Of Motion

Although the dancer is still, the pose contains the memory of steps. The crossed right leg tucks under the tutu like a coiled spring. The left leg lengthens into a clean diagonal whose point touches the floor with whispering precision. The right hand’s grip at the waist suggests rehearsal discipline; the left hand, hovering open, keeps the upper body from hardening into rigidity. The head tilts slightly, the gaze set to the side with an inward steadiness. What remains is not spectacle but poise: the moment between phrases when balance gathers for the next movement.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The light is even and reflective, the kind that Matisse prized in Nice. Shadows are chromatic rather than black. The tutu’s underside tones through slates and lavender; the tights deepen into raspberry near the knee; the face carries quiet half-tones of beige and gray that accept reflections from the green and ultramarine bands. Highlights are small and exact: a milky spot on a pearl, a cool stroke along the shoulder, a sharp kiss of white on the slipper. This diffusion keeps the value range moderate so color can carry volume and the stage can remain calm.

Drawing And The Breathing Contour

Contour is the painting’s quiet authority. The jawline curves with a single, confident sweep; the nose sits as a quick wedge; the brows are abbreviated arcs that set expression without fuss. The straps of the bodice are clean bands that mark the turn of the shoulder. The leg’s diagonal is drawn in one elastic line that tightens at the ankle and relaxes across the instep. Even the banded background, though flat, is edged with living, hand-drawn borders, preventing the planes from becoming mechanical. Because edges breathe, the large color fields feel like air rather than poster board.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Depth is not denied but kept on a short leash. The green, ultramarine, and black fields behave as flat screens pushed close behind the sitter. Overlaps—tutu over blue, leg over black, slipper on the orange floor—provide just enough recession to settle the body. This productive flatness keeps attention on where relations matter: the contact zones between colors and the orchestration of pattern and pose. The room is not a window to look into; it is a surface to inhabit with the eyes.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse often likened painting to music, and the score here is easy to hear. The background bands sustain long chords. The tutu pulses with a regular, circular rhythm. The pearl necklace performs a brief, bright ostinato around the neck. The red leg diagonal reads as a solo line, crossing the established harmonies at a clear angle. The eye makes circuits from head to necklace to bodice to tutu to leg to slipper to floor and back again, discovering on each pass small consonances: a green strap answering the top field, a black motif in the bodice echoing the dark band, a rosy highlight on the tights matching the floor’s warmth near the toe.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“The Ballet Dancer” speaks directly to Matisse’s other stage pictures from the later 1920s. It shares with “Ballet Dancer Seated on a Stool” the ring of tulle and the diagonal leg, but the present work opens the space with wider color bands and a more graphic poster sensibility. It converses with the Nice odalisques by swapping patterned walls and props for cleaner planes; the decorative ideal remains, but it has been distilled. It also foreshadows the late paper cut-outs in its reliance on broad fields, emphatic edges, and interlocking shapes that read almost as silhouettes.

Psychological Tone And Modern Agency

The dancer’s presence is contemporary and untheatrical. She faces us with quiet confidence, lucid rather than coy. The pearls and patterned bodice are not costume extravagances but measured notes that keep the head in dignified focus. The compact set—just colors and a ledge—removes anecdote and lets agency reside in the way the body is held. Matisse’s interest is not backstage narrative but the ethics of balance: how a person occupies a space with clarity and calm.

Tactile Intelligence And The Reality Of Paint

Texture is varied without noise. The green and ultramarine fields are brushed thinly so undercolor breathes through, giving the sense of air behind the figure. The tutu’s whites are thicker, with ridges that catch light like stiffened tulle. The tights are painted with longer, elastic strokes that wrap the leg. Facial features are set with scrapes and small, dense notes that convince without description. This orchestration of touch keeps the picture sensuous while preserving its graphic discipline.

Evidence Of Process And The Earned Harmony

Look closely and small adjustments reveal the search for equilibrium. A softened outer edge of tutu indicates a shift to better balance the leg’s angle; a reinforced curve at the shoulder clarifies the strap’s path; a re-sited pearl brightens the turn of the head. These traces confirm that the serenity we feel is not formula; it is the outcome of tuning intervals until the chord rings true.

Why The Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Return to it and a new hinge appears: a pale reflection from the green field echoing on the shoulder, a black motif in the bodice aligning with the bar below, a pearl glint recruiting a highlight from the slipper, a thin violet in the tutu answering the ultramarine band. None of these single insights exhausts the work; they accumulate into a durable satisfaction that invites daily looking.

Conclusion

“The Ballet Dancer” converts a quiet rehearsal moment into a manifesto for modern harmony. With a handful of large planes, a circular tutu, a disciplined diagonal, and a few precise ornaments, Matisse shows how color can act as architecture, how pattern can regulate time, and how a figure can radiate agency without theatrics. The painting’s clarity is generous rather than severe, its calm earned rather than bland. It remains one of the most inviting doors into the Nice period’s belief that beauty is the spacing of differences—warm against cool, circle against band, stillness against remembered motion—held in lucid balance.