Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Face Built from Light and Brush

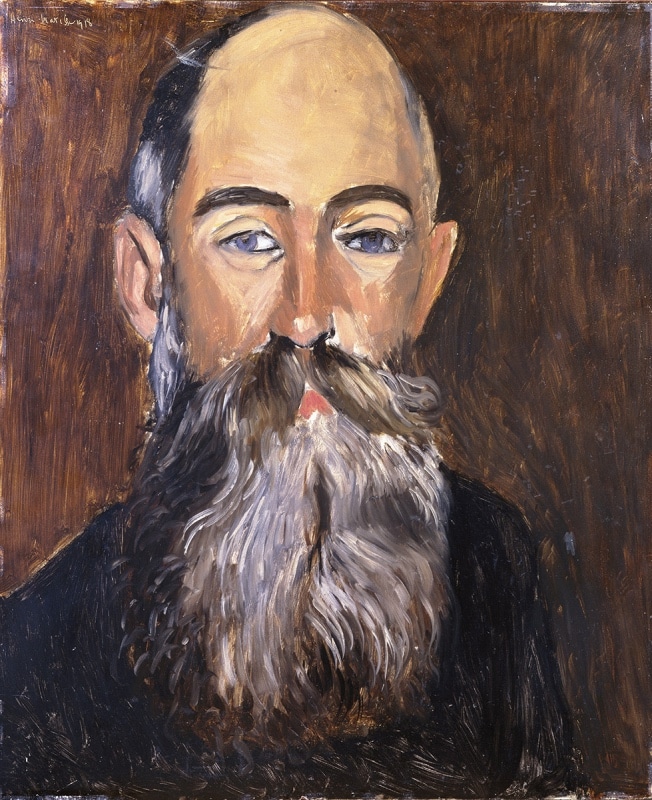

At first encounter, “The Antiquarian Georges Joseph Demottev” confronts the viewer with the authority of a head that seems carved from air and paint. The composition is a tight, frontal portrait: a high, polished cranium; cool, alert eyes; and a cascading beard rendered in fast, rhythmic strokes that register like a tide of silver and smoke. Behind the sitter lies a warm brown field that neither recedes nor advances, but holds the figure in suspension. Nothing distracts—no hands, no tabletop, no studio clutter—only the drama of physiognomy. Matisse condenses likeness to essentials and then orchestrates those essentials into a modern icon.

Who the Sitter Is and Why It Matters

Georges Joseph Demotte was an antiquarian and art dealer, a figure whose profession was to adjudicate the value of objects and bring the past into the commerce of the present. Matisse seizes upon the paradox of such a role: the sitter looks both of his time and outside it. The bald dome and cut-straight eyebrows suggest a mind sharpened by appraisal; the opulent beard evokes older painterly lineages—Rembrandt’s sages, Frans Hals’s scholars, even Byzantine patriarchs whose beards act as emblems of station. By focusing on head and beard, Matisse acknowledges the sitter’s labor as essentially intellectual and historical. The portrait is not a costume picture. It is a concentrated statement about judgment, memory, and time.

Composition: A Symmetry Disturbed by Life

The head centers the square canvas, a compositional choice that confers dignity and steadiness. Yet Matisse refuses static symmetry. The shape of the cranium tilts minutely; the beard swells more on one side than the other; the ear on the right catches more light; the eyes, though aligned, register slightly different intensities. The result is a portrait that breathes. The square support intensifies the vertical thrust of the figure while the beard’s triangular cascade grounds the head like a plinth. The composition reads as architectural: dome, column, base. This simple architecture is then animated by brushwork, which supplies the pulse.

Palette: Warm Earths, Cool Grays, and Living Blacks

The color set is reserved but eloquent. The background is a warm brown built from earth pigments that echo the varnished tones of old wood. Skin is a blend of peach, ochre, and small cool notations; the cools sit mostly at the periphery—the temples, the eyes’ white, the sheen at the top of the head—so that warmth and life collect toward the center. The beard is an orchestra of grays: slate, pearl, smoke, graphite, each laced with slender lines of black that articulate volume without deadening it. Matisse’s black is never merely outline; it is a full pigment that creates internal shadow and rhythm. Where many portraits rely on chromatic spectacle, this one achieves presence with modest means: earth, flesh, metal, and air.

Brushwork and the Language of Hair

The beard is the painting’s bravura passage. Long, loaded strokes sweep downward, each stroke splitting at the end into a fork or curving into a hook, mimicking the logic of hair without imitating any single strand. Shorter, cross-directional touches break the flow, suggesting eddies and depth. Small, sharp lines—nearly calligraphic—describe the mustache’s twist and the beard’s crisp outer edges. This orchestration of marks accomplishes three tasks at once: it models the beard’s volume, it directs the viewer’s gaze, and it establishes tempo. One can almost read the sequence of motions by which Matisse painted: gather paint, pull, flick, restate. The head above, by contrast, is handled with broader, smoother planes. The opposition—smooth dome, agitated beard—enlivens the portrait and metaphorically pairs thought with speech, idea with utterance.

Drawing Inside Color

Matisse’s drawing is inseparable from his paint. He does not finish a form and then encircle it with line; the contour happens as part of the stroke. Along the brow ridge, a thin dark seam tightens where the bone turns and loosens where flesh softens. Around the ears, the contour both clarifies silhouette and darkens the inner cavities. At the shoulders, the black of the coat lifts from the background by a single zone of slightly cooler, denser paint. This approach fuses structural clarity with painterly breadth: no descriptive filigree, yet nothing vague.

Light as Climate, Not Spotlight

Illumination in the portrait is not a theatrical beam but a pervasive climate. Highlights glide across the skull in a saffron crescent; the beard glints in icy flashes; the background absorbs light without flattening. Shadows are rarely abrupt; they are achieved by temperature shifts—warm to cool, opaque to semi-opaque—rather than hard edges. The sitters’ eyes receive special handling: the sclera is not white but a tempered cool; the irises carry a faint violet; the upper lids cast shallow cool shadows that settle the eyes into the head. This climate light creates a space for contemplation rather than drama, befitting a sitter defined by scrutiny and knowledge.

The Psychology of the Gaze

The portrait’s power hinges on the eyes. They are not sharply detailed, yet they command. Matisse sets them under strong, arched brows and gives them the slightest asymmetry in focus. The right eye appears minutely more open, the left minutely more veiled, as if the sitter blinks between outward attention and inward evaluation. This oscillation aligns with the profession of an antiquarian: one eye on the object, one eye on the tradition that grants it meaning. The mouth is hidden by mustache and beard, which throws communicative weight onto the gaze. Speech is withheld; judgment is visible.

The Background as Active Field

The background’s brown is hardly neutral. Laid in with broad, directional strokes, it participates in the portrait’s rhythm. Its vertical sweeps echo the beard’s fall; its lighter scrapes near the skull crown emphasize the head’s polish. The background therefore behaves like a resonant wood panel in a musical instrument: it amplifies and warms the tones placed upon it. Matisse often used patterned backdrops for decorative play; here he exercises discipline, discovering variety within limitation.

The Balance of Modernity and Permanence

Matisse’s portrait embodies a negotiated modernism. It is not academic modeling, nor is it the raw distortion of the Expressionists. He reduces features to planes, quickens surfaces with unblended strokes, and gives black a structural role. Yet he preserves proportions, maintains dignity, and locates the individual rather than a type. The result feels at once contemporary to 1918 and timeless. One could imagine the head on a Roman coin or in a 17th-century Dutch canvas; it also reads like an image one might encounter in a modern studio. This elasticity suits a subject who dealt in the commerce of past and present.

The Square Format and the Ethics of Frontal Address

The square is a demanding format for portraiture because it refuses the easy vertical emphasis of a rectangle. Matisse answers by structuring the head as a pyramid within the square. The triangle of the beard anchors the lower half; the skull’s rounded apex reaches toward the top edge without touching it; the ears set the lateral span. This architecture produces a frontal address that feels ethical rather than confrontational. The sitter meets the viewer evenly, without aggrandizement or flattery. The square confers parity: viewer and sitter occupy equivalent visual weight.

The Beard as Measure of Time

In historical portraiture, beards often serve as emblems of age, wisdom, or religious status. Matisse updates the emblem by making the beard a record of motion and paint. The streaks of gray, white, and sable imply not only hair’s material reality but time’s river. Each brush-pass is a decision laid in the present that points to the past and the future—the very dynamic that defines an antiquarian’s work. The beard also affects the painting’s acoustics. Its dense strokes lower the register, making the flesh’s lighter planes sound brighter. The painterly beard, then, is both subject and instrument.

Economy and Exactitude

One of the portrait’s most impressive qualities is its economy. Matisse uses a limited number of marks to do multiple jobs. A swift curve defines the nostril, deepens the philtrum’s shadow, and energizes the central axis. A flick of light on the ear’s rim both situates the ear in space and echoes the skull’s highlight. The coat is indicated by weight and direction rather than buttons or seams, allowing viewers to supply missing specifics from their own reservoir of seeing. This economy is not laziness; it is exactitude—knowing what to say and what to leave implicit so that the sitter’s presence remains the painting’s story.

Comparisons and Context within Matisse’s 1917–1919 Portraits

Placed beside Matisse’s portraits of the same period—Laurette’s various heads, the severe “Portrait of George Besson,” and other Nice-period likenesses—this canvas reads as a masculine counterpoint to the artist’s studies of women posed against luminous walls. The Laurette pictures lean on decorative color and the play of costume; the Besson head pursues a chiseled, almost mask-like severity. “The Antiquarian Georges Joseph Demottev” fuses the two paths: it holds onto the expressive power of contour while exploiting painterly texture to suggest changing light and living flesh. This synthesis signals the steadier, more atmospheric language that would characterize Matisse’s 1920s portraiture.

Guided Close Looking: A Path Through the Painting

Enter at the forehead’s highlight, where a warm crescent carries you from left temple across the dome. Follow the arc down to the right brow; note the fine dark seam that tucks the eyelid under the ridge. Drop into the eye’s cool interior; catch the violet whisper where iris meets white. Cross the bridge of the nose—one decisive plane shift—descending to the mustache’s darker bar. Allow your gaze to fall into the beard; track a long gray stroke to its forked end, then counter with a short, upward stroke that catches light. Move laterally to the left, where the beard bulges and coils; sense the painter’s hand pivoting at the wrist. Return upward along the left ear’s lit rim; pause at the eye’s second cool interior; then retreat to the background’s vertical field, recognizing how those strokes echo the beard’s rhythm while keeping their own temperature. After this circuit, the portrait’s internal music becomes audible: crest and trough, warm and cool, plane and strand.

The Ethics of Restraint and Respect

There is no caricature here. Matisse resists exaggeration that might win instant likeness at the cost of dignity. He withholds accessories that would tether the sitter to a single anecdote. Even the signature lay low in a corner, subordinated to the head’s sovereignty. This restraint, paradoxically, increases intimacy. By not telling us everything, the painting leaves room for encounter. The sitter becomes someone one could meet, not merely recognize.

Why the Portrait Still Feels Fresh

Contemporary viewers live among faces mediated by cameras, filters, and screens. This painting offers another kind of presence: one translated through a hand that thought in color and stroke. Its freshness comes from the visibility of process—a record of decisions rather than a display of effects. It also comes from the painter’s belief that a few well-tuned relations can carry the full weight of character. The portrait’s quiet ambition is to honor looking as a form of knowledge, a proposition that remains urgent.

What the Painting Teaches

For painters, designers, and viewers, the portrait is a concise manual. Establish a clear structural armature; choose a limited palette that suits the subject’s temperament; treat darks as active partners; let brushwork do multiple jobs; model by temperature shifts rather than heavy chiaroscuro; and locate psychology in the meeting of proportion, light, and rhythm rather than in theatrical gesture. Above all, let respect guide economy. Matisse’s few, firm strokes do not merely describe Demotte; they make a space in which the antiquarian’s presence can be met.

Conclusion: Presence, Judgment, and the Music of Paint

“The Antiquarian Georges Joseph Demottev” is less a transcription of features than an arrangement of forces—warmth and coolness, plane and strand, symmetry and deviation—that coalesce into a singular presence. Matisse sets intellect under a dome of light, lets history tumble like a beard, and binds the whole with a background that hums like seasoned wood. The painting’s quiet conviction is that character can be built from relations, and that a modern portrait can achieve permanence without bombast. We meet a man whose life was spent weighing the past; in Matisse’s hands, he becomes an emblem of looking itself.