Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

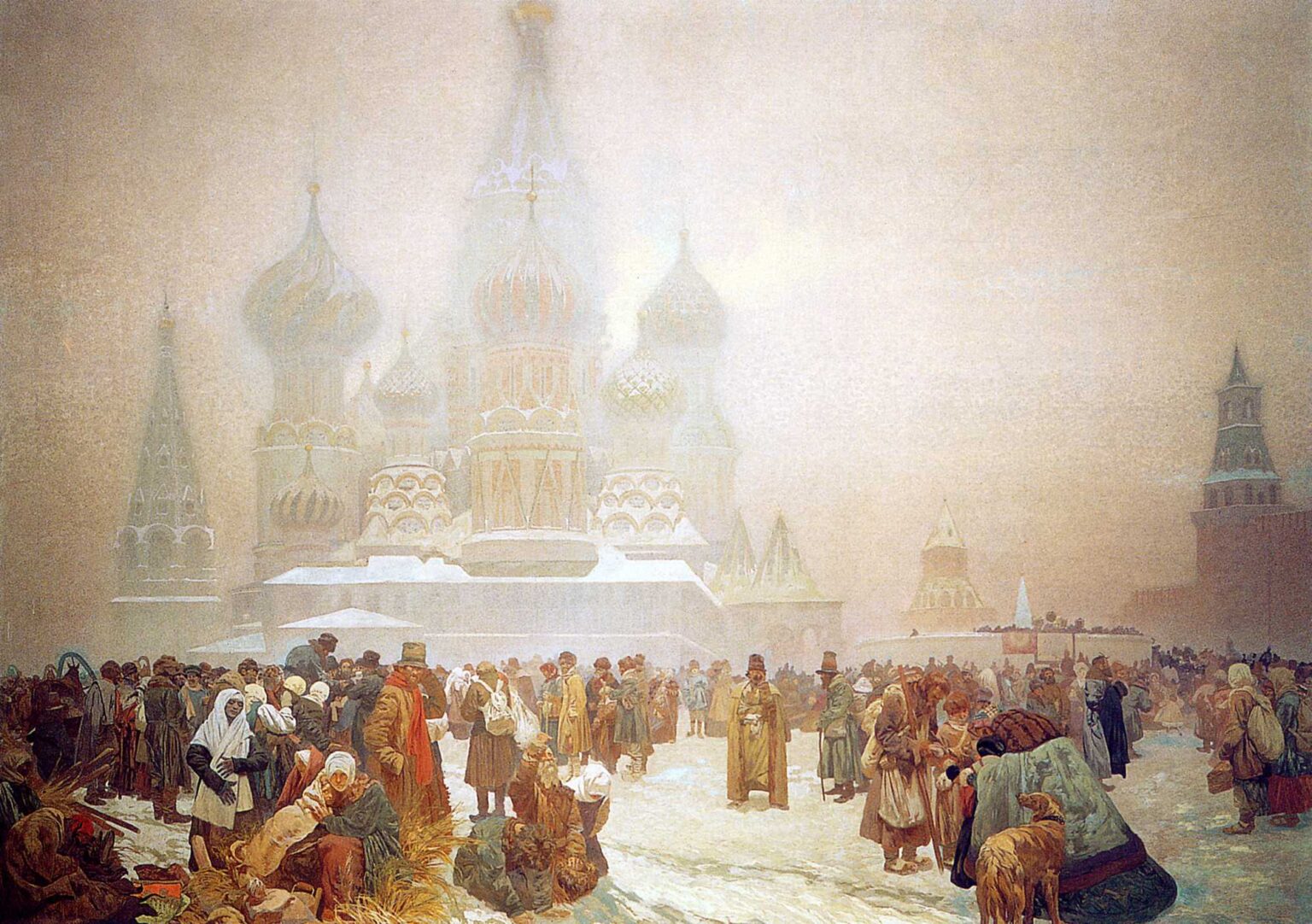

Alphonse Mucha’s “The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” (1914) is one of the most haunting chapters in his monumental cycle, The Slav Epic. Where other panels in the series stage councils, baptisms, or legends with theatrical clarity, this canvas is a study in ambiguity. A crowd gathers in winter light before the onion domes of Moscow—St. Basil’s Cathedral emerging like a dream from frost and fog. The abolition has been declared; the word freedom circulates; and yet the faces turned to one another express perplexity as much as celebration. Mucha composes a wide public square filled with small human dramas, then shrouds the scene in a pale atmospheric veil that turns history into weather. The result is an image that honors a watershed moment while refusing triumphal simplification.

Historical Context and the Stakes of Emancipation

The scene looks back to the 1861 emancipation under Tsar Alexander II, when tens of millions of serfs were legally freed from feudal bondage. The reform promised mobility and dignity, but it also tethered many former serfs to long redemption payments and communal obligations that blunted the meaning of liberty. Mucha, working in 1914 on the eve of cataclysm, understood that the abolition inaugurated a period of hope threaded with hardship. Rather than depict the Tsar or the signing of the decree, he turns to the everyday consequences: a square where news and uncertainty mingle, where peasants, city dwellers, clergy, and soldiers test the new social weather by simply standing together. The abolition becomes not a ceremony but a condition that must be felt in bodies and conversations.

Composition and the Architecture of Weather

The canvas is built on two massive registers. Above, a vast, vaporous sky swallows the crenellated horizon of Moscow; the bulbous domes and slender towers of St. Basil’s seem to condense from the mist, their colors faint as breath on glass. Below, a broad band of human life extends from left to right across snowy ground. This horizontal field of people anchors the painting against the vertical pull of the cathedral’s towers. The lower edge is crowded but not chaotic: clusters form around baskets of straw, around children, around figures exchanging words or goods. The composition reads like a frozen tide—one long swell of community that pauses beneath a city made spectral by cold.

Light, Color, and the Emotional Temperature of Fog

Mucha abandons the saturated posters’ palette in favor of winter’s restrained spectrum. Cream, ash, and celadon rule the upper half, while the crowds bring warmer browns, bottle greens, and russets into the lower register. Snow reflects the same diluted light that turns the cathedral ghostly; the people appear warmed by their clothes and each other rather than by the sun. Nothing is theatrically lit. Instead, illumination diffuses, and tone knits forms into a single, breathable atmosphere. This chromatic discretion is not mere description. It is an ethics of seeing freedom as fragile. A fog of uncertainty hangs over the newly emancipated, and Mucha incarnates that uncertainty as a meteorological fact.

The Cathedral as Icon and Mirage

St. Basil’s Cathedral rises like a memory rather than a building. The onion domes seem to fade and reappear as the eye sweeps across them; ornament dissolves into the same silvery air that swallows distant figures. As an architectural presence, it anchors national identity; as a specter, it warns that institutions can recede from those standing in the cold. Mucha resists turning the church into a political emblem and instead allows it to become the symbolic horizon of the painting: ancient, beautiful, a little unreachable. Liberation happens in its shadow, but not under its direction. The sacred skyline looks on as people test new freedoms on the ground.

The Crowd as a Portrait of Social Weather

The lower band of the picture is a gallery of micro-histories. Women in kerchiefs cradle infants. A bent figure tends straw or kindling near the left edge. A man in a long coat consults a document. Children tug at sleeves; a vendor counts coins; an old soldier wrapped in a cloak leans on his stick as if listening to rumor. Dogs nose through the snow, indifferent to decrees. Mucha’s crowd is not anonymous; it is particular. Every stoop and gesture feels observed. Yet he resists individual portraits. Faces are slightly generalized, as if to insist that emancipation is shared experience rather than a series of singular destinies. The viewer is invited to roam, to eavesdrop visually, to assemble a meaning from small, human instances.

Gesture, Conversation, and the Sound of Change

Because the painting mutes color and avoids protagonists, gesture carries the drama. A woman kneels to console another whose body leans forward in exhaustion. Men stand with arms crossed in guarded posture, as though freedom requires caution. A boy looks up, mouth open, at a taller figure who explains or negotiates. Hands extend to offer bread, to weigh money, to touch a sleeve. In these ordinary motions Mucha locates the true theater of reform: the recalibration of obligations and expectations in thousands of tiny exchanges. Abolition is not simply proclaimed; it is enacted in the way people speak, listen, and hold themselves in public.

Snow, Straw, and the Material Grammar of Poverty

Mucha peppers the foreground with straw, sacks, baskets, and bundles. Straw lies like yellow punctuation against the white ground, creating warm passages that draw the eye to groups huddled for warmth or trade. Its presence is iconographic. Straw is labor, bedding, fuel—an index of material life in winter. The abolition did not deliver prosperity; it offered legal change to bodies still negotiating cold and hunger. By giving straw a visual role, Mucha writes poverty into the painting’s grammar without spectacle or sentimentality.

Space, Distance, and the Ethics of Witness

The viewer stands neither among the people nor far above them. The vantage point is slightly elevated but intimate, as if one is on a shallow platform at the square’s edge. This position matters. It allows for sympathetic survey: we can read groups and put them in relation, but we cannot retreat into the safety of panorama. The painting asks for witness rather than mastery. We are implicated in the crowd’s cold, its hesitations, its small mercies. Even the cathedral’s haze participates in that ethics; it refuses to be a backdrop for heroism and instead becomes a canvas for breath and time.

Line, Edges, and the Soft Discipline of Drawing

Mucha’s line, so crisp in his lithographs, is softened here to suit the snow’s hush. Contours thicken only where needed: along a cloak hem, at the silhouette of a hat, in the arc of a dog’s back. Elsewhere edges dissolve into atmospheric gradation. This soft discipline allows the crowd to hold together as a field while giving each figure enough definition to read. The cathedral’s outlines are nearly undone, but never to the point of confusion. Mucha uses drawing to calibrate proximity—sharper where we stand, gentler as the eye moves back—so that space itself becomes part of the narrative of uncertainty and hope.

Silence and the Memory of Decree

Although one imagines talk and the crunch of boots, the painting’s dominant mood is a quiet that feels more moral than acoustic. Snow muffles sound, fog softens edges, and the viewer senses a collective pause around an invisible document. The decree abolishing serfdom is not shown, but its afterimage saturates the square. The people are not cheering; they are thinking. Mucha honors the mental labor of understanding freedom. He paints the interval between news and action, a suspended time when a society tries to measure what has changed.

The Child, the Elder, and the Measure of Reform

Throughout the crowd, the artist places the very young and the very old. A toddler bundled in a shawl stares out from a mother’s lap; bent figures sit close to the ground, hands extended to pets or to one another. These bookends of life confront the promise of emancipation with simple questions: Will children inherit a better order? Will elders—formed by the old system—find dignity in the new? Mucha’s attention to these bodies makes the abstract word freedom answerable to dependence and age.

Dogs, Borzois, and the Edge of Privilege

Near the right margin a tall dog, likely a borzoi, presses close to a richly cloaked figure; elsewhere mongrel dogs skitter between boots. The pairing is not accidental. The elegant hound—long associated with nobility—shares space with peasants and beggars. The abolition has brought classes into new proximity without erasing difference. By giving the borzoi an affectionate lean and the mongrels a cheerful freedom, Mucha lets animals comment on social relations with a gentle humor that keeps the scene human.

The Kremlin Walls and the Crowd’s Geometry

At the far right, the crenellated wall and tower cut diagonals into the fog. A line of onlookers gathers along the parapet, tiny against the stone. Their presence mirrors the crowd below in miniature and suggests the continuity of institutions that will observe and regulate the newly emancipated. Yet the wall’s darkness is softened by haze, as if authority, too, must learn to see in new light. Mucha always balances architecture and community so that neither becomes mere ornament; here the walls serve as a reminder of history’s endurance even as they fade into a winter sky.

Technique, Scale, and the Breath of the Surface

Like other panels of The Slav Epic, the painting is executed on monumental canvas with matte, translucent layers that let color breathe rather than glare. The technique suits the fog. Thin veils of gray and cream allow pentimenti and under-hues to flicker through, creating the sensation of air suspended with ice particles. Brushwork over snow is broad and horizontal, while garments are built from layered strokes that suggest wool, fur, and worn cloth. The surface has the quiet authority of fresco without the chalk; it feels lived-in, as if the scene emerged from weeks of weather rather than hours of dramatic sun.

Relationship to the Larger Epic

Placed within The Slav Epic, this panel functions as a late, modern counterweight to the mythic origins and medieval councils that precede it. The series moves from starry nights of survival to vernacular worship to battles and reforms; by the time we reach Moscow’s square, the story has shifted from legends to the urban crowd. Mucha’s stylistic choices track that change. The supernatural apparitions of earlier canvases give way to human density; the gold of saints’ halos is replaced by the gray of kissed breath in winter air. And yet the epic’s central conviction remains: the dignity of a people is composed in public attention, in the way bodies gather and listen. Even in fog, the gathering persists.

Freedom, Ambiguity, and the Refusal of Propaganda

It would have been easy to paint the abolition as a parade of banners or a portrait of the Tsar distributing largesse. Mucha refuses propaganda. He shows a people confronted by freedom’s complexity: legal change colliding with poverty, hope balancing fatigue, institutions looming as promise and threat. The fog is not an evasion; it is a diagnosis. It tells the viewer that emancipation blurs before it clarifies, and that the measure of reform is found in bread, shelter, and the warmth of shared bodies in a cold square.

Contemporary Resonance

The picture speaks to any society emerging from legal injustice into uncertain liberty. The crowd’s questions are perennial: What does freedom feel like when money is scarce and shelter cold? What new obligations replace the old ones? How do institutions learn to see those they once bound? Mucha answers without slogans. He trusts that the ethics of attention—the careful painting of hands, faces, and small exchanges—can itself be a political act. The image makes us present to one another, which is the first kindness of civic life.

Conclusion

“The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” is a winter meditation on freedom. Its city dissolves into fog; its people assemble in modest warmth; its dogs wander between coats and skirts; and its snow holds footprints that lead in every direction. By suspending the scene between revelation and routine, Mucha honors the complexity of reform. The emancipation is not a radiant sunrise; it is a day of pale light in which faces turn to one another to ask, What now? In that question lies the painting’s enduring power. It invites viewers to imagine freedom not as spectacle but as conversation in the square—a work of patience, care, and shared breath.