Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

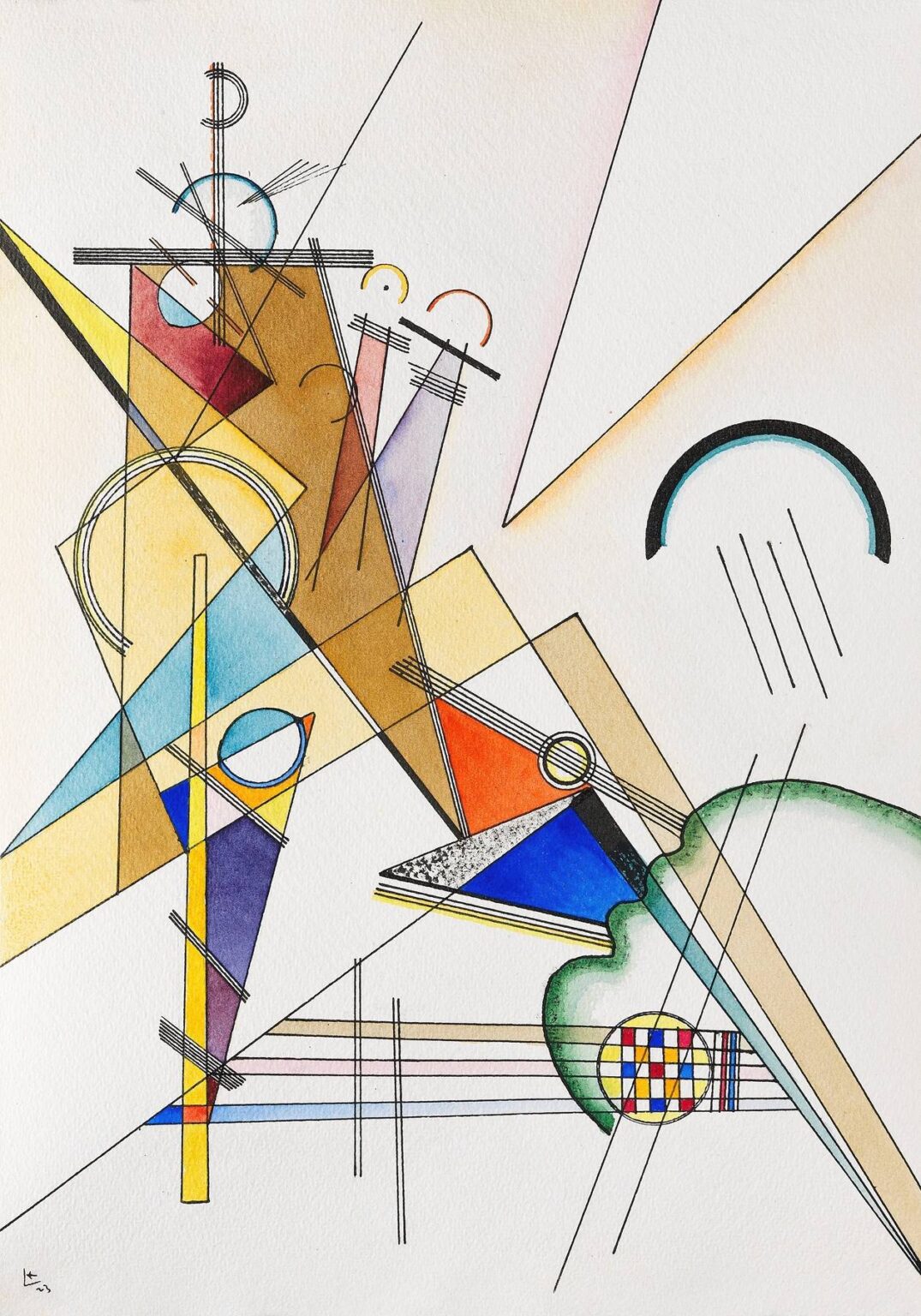

In Textile (1923), Wassily Kandinsky transforms his synesthetic vision into a composition that evokes the interlaced threads of a richly woven fabric. Executed as a chromolithograph during his early Bauhaus period, this work celebrates both the precision of geometry and the spontaneity of painterly gesture. Across a luminous white ground, sharp diagonals of muted beige and pastel pink slice through intersecting planes of ochre, red, blue, and violet. Thin black lines act as warp threads, while arcs and circular motifs resemble weft yarns coursing through the composition. The result is a tapestry of form and color, alive with rhythmic energy and spiritual resonance. Throughout this analysis, we will explore the painting’s historical context, Kandinsky’s theoretical foundations, its formal construction, technical mastery, and the emotional and symbolic depth that makes Textile a quintessential example of abstract modernism.

Historical and Artistic Context

By 1923, Kandinsky had firmly established his role as a leading proponent of abstraction. His move from Munich to Weimar in 1922 to teach at the newly founded Bauhaus marked a period of intense formal investigation. Surrounded by architects, designers, and fellow artists, Kandinsky refined his theories of form and color, emphasizing clarity, precision, and pedagogy. The Bauhaus ethos of uniting art and craft found a resonant echo in the theme of Textile, a medium traditionally associated with artisanal weaving. Concurrently, the aftermath of World War I had left Europe yearning for renewal, and abstraction offered a way to transcend the horrors of conflict. Kandinsky’s lithographic experiments at this time distilled his spiritual beliefs into crisp geometric vocabulary, and Textile emerges from this crucible of interdisciplinary exchange and utopian aspiration.

Kandinsky’s Synesthetic Philosophy

Central to Kandinsky’s art was the belief that painting could achieve a direct parallel to music. He conceived of colors and shapes as “visual notes” capable of evoking inner emotional responses. In Textile, the interplay of diagonals, verticals, and horizontals functions like intersecting melodic lines, while the color contrasts mimic harmonic progressions. Kandinsky’s writings—most notably On the Spiritual in Art (1912)—outlined how form and color could communicate spiritual truths unmediated by representational content. Through synesthesia, viewers are invited to “hear” the composition: the warm ochre planes resonate like low brass, the cool blue triangles sing like woodwinds, and the intersecting black lines form a contrapuntal scaffold that binds the visual melody into a coherent symphony.

Thematic Resonance of Weaving

Although abstract, Textile evokes the archetype of woven fabric. The black linear elements suggest the warp threads—vertical supports that give structure—while the colored planes and arcs function as the weft, weaving across and through. This metaphor speaks to the Bauhaus ideal of integrating art and craft, as well as Kandinsky’s fascination with the unity of disparate elements. The weaving theme also symbolizes the interconnectivity of creative disciplines: architecture, painting, music, and textile design. By rendering a “visual textile,” Kandinsky pays homage to the Bauhaus curriculum, which prized hands‑on exploration of materials. At the same time, the painting’s spiritual impetus aligns with his longstanding quest to weave a harmonious fabric of inner necessity.

Formal Composition

Textile unfolds within a vertical format dominated by a large beige diagonal that rises from lower left to upper right, creating a dynamic thrust. A complementary pink diagonal echoes this motion, generating a sense of expansion. Intersecting planes of ochre and red form triangular wedges at the center, balanced by smaller blue and violet triangles near the lower left. Delicate black lines—sometimes thickened into bands—cross at precise angles, defining geometric compartments. Arcs punctuate the linear grid, their curved forms softening the rigidity of straight edges. At the lower right, a circle filled with a checkerboard of yellow, red, and blue squares suggests a focal knot or anchor point. Through these interwoven shapes, Kandinsky constructs a network of tensions and harmonies that engage the eye in perpetual movement across the surface.

Color Harmony and Contrast

Kandinsky’s mastery of color theory shines in Textile. The muted beige and pastel pink serve as neutral backgrounds that allow the more vivid ochre, red, blue, and violet to glow with heightened intensity. He applies his principles of complementary and analogous contrast: the blue triangles contrast dynamically with the ochre field, while the red planes resonate warmly against the beige diagonal. The tiny yellow squares within the circular grid act as scintillating highlights, akin to the flicker of light across a woven textile. These color interactions generate an emotional chord: warmth and serenity, vitality and repose. By calibrating hue, saturation, and tonal value, Kandinsky ensures that each shape retains its individual charge while contributing to the work’s unified emotional spectrum.

Dynamics of Line and Movement

Line in Textile functions as both literal thread and abstract gesture. The prominent black diagonals carve the composition into directional zones, suggesting upward lift and forward drive. Finer black strokes—short horizontal hatchings and vertical markings—create rhythmic subdivisions, akin to the interlaced threads of weaving. These hatchings often bracket color fields, reinforcing their edges like binding stitches. Curving lines pierce through angular segments, injecting lyrical counterpoint. The overall rhythm of line alternates between measured discipline and lively swing, echoing the improvisational quality Kandinsky admired in music. This dynamic oscillation sustains visual momentum, guiding the viewer through a choreographed dance of geometric interplay.

Spatial Depth and Layering

Despite its flatness, Textile achieves a convincing sense of spatial depth through overlapping shapes and the interplay of opacity and transparency. Some color planes appear to float above others, their edges crisply defined by the black warp lines. In contrast, triangular fields sometimes overlap with softened contours, suggesting translucency. The diagonal planes slice through multiple layers, heightening the perception of a three‑dimensional weave. The circular grid on the right seems to recede into the background at moments, then pop forward when contrasted with a darker adjacent plane. Kandinsky thus constructs a spectral architecture of shifting planes, inviting viewers to explore an abstract topography that unfolds through careful compositional layering.

Technical Craftsmanship of Lithography

As a chromolithograph, Textile required Kandinsky to coordinate multiple stone plates—each inked with a distinct color. Precision in registration was essential to align the black relief lines with the underlying color shapes. The soft gradations of beige and pink likely derive from crayon or brush application on the lithographic stone, imparting a subtle textural warmth. The colored shapes were then printed in successive passes, each demanding meticulous calibration. Kandinsky’s willingness to incorporate slight variations in ink density and paper absorption lends the print a handcrafted vitality. The fidelity of line and the richness of color fields attest to his rigorous craftsmanship and deep understanding of lithographic potentials.

Symbolic and Spiritual Underpinnings

While entirely abstract, Textile resonates with Kandinsky’s spiritual inquiries. The weaving metaphor extends beyond craft to symbolize the interconnectedness of human experience and cosmic order. The intersecting diagonals may represent converging paths of spiritual ascent, while the circular checker grid signifies unity within diversity—a cosmic mandala rendered as textile. Kandinsky viewed abstraction as a means to express universal spiritual realities, bypassing the constraints of representational imagery. In this sense, Textile offers a transcendental vision: an abstract loom upon which the threads of material and immaterial, form and spirit, are interwoven into a resonant whole.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

Encountering Textile can stir a range of emotional responses—curiosity, wonder, inner calm, and uplift. The work’s geometric clarity provides intellectual satisfaction, while its vibrant color chords and rhythmic line work spark intuitive, visceral reactions. Viewers may sense echoes of memory—glimpses of patterned rugs, sonar readings, or stained glass windows—yet the abstraction defies singular interpretation. Kandinsky designed his abstractions to activate the viewer’s inner necessity, allowing each person’s psyche to fill in personal associations. Textile thus becomes a mirror for the soul, reflecting individual emotional landscapes even as it conveys a universal harmony.

Place Within Kandinsky’s Oeuvre

Textile occupies a key transitional moment in Kandinsky’s career. It synthesizes the free‑wheeling abstraction of his pre‑war “improvisations” with the controlled geometry he would refine at the Bauhaus. Compared to his earlier canvases—awash in swirling color and spontaneous brushwork—this 1923 lithograph reveals a leaner, more architectonic vision. Yet the spiritual fervor and synesthetic impulse remain intact. As he continued into the late 1920s and 1930s, Kandinsky would further distill his forms into basic geometric units, but Textile stands as a luminous bridge between lyrical freedom and crystalline structure.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Nearly a century after its creation, Textile continues to inspire artists, designers, and scholars. Its metaphor of weaving resonates with contemporary debates around interdisciplinarity and the blending of art, craft, and technology. Graphic designers draw upon its bold diagonals and color harmonies to convey movement and cohesion. Digital artists reference its rhythmic grid and layered transparency in generative works. In academic discourse, Textile serves as a prime example of Kandinsky’s synesthetic theories and his skillful adaptation of lithography to abstract ends. The print’s ongoing relevance lies in its demonstration that abstraction can be both formally rigorous and deeply expressive, offering viewers a timeless tapestry of inner light and harmonious resonance.

Conclusion

Wassily Kandinsky’s Textile (1923) stands as a masterful chromolithograph that interweaves geometry, color, and line into a visual fabric of profound spiritual and emotional depth. Through its layered planes, intersecting diagonals, and rhythmic arcs, the print emulates the structure of woven textiles, while its synesthetic underpinnings invite viewers to “hear” the composition as visual music. As both a reflection of Bauhaus ideals and a culmination of Kandinsky’s synesthetic philosophy, Textile continues to captivate with its harmonious fusion of precision and lyricism. Even today, its dynamic interplay of form and void offers an abstract sanctuary—an artistic loom upon which the threads of color and line converge to uplift the human spirit.