Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

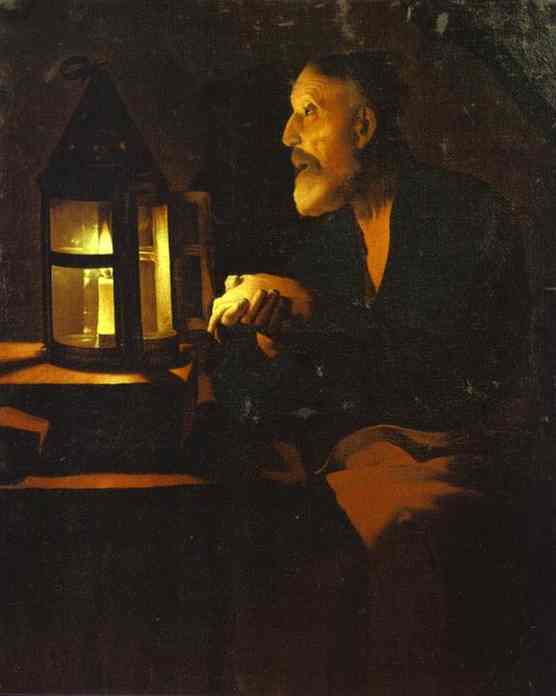

Georges de la Tour’s “Tears of St. Peter” (1648) belongs to the artist’s profound series of candlelit nocturnes in which light, gesture, and silence express the deepest movements of the soul. The painting shows an elderly man seated beside a lantern. His hands are clasped, his mouth slightly open as if mid-prayer, and his eyes turn toward the glow that breaks the dark. There are no crowds, no soldiers, no crowing rooster—only a solitary figure and a modest pool of light. With that austerity, de la Tour transforms a familiar Gospel episode—Peter’s repentance after denying Christ—into a private vigil where contrition and hope quietly share the same breath.

The Narrative Compressed to an Hour of Vigil

The Gospels describe Peter’s triple denial, his sudden recognition of failure, and his weeping. Seventeenth-century painters often depicted the dramatic instant of tears with a rooster, a skull, the keys of the Church, or a burst of celestial light. De la Tour compresses the story into the low, sustained hour afterward. Peter has retreated from the courtyard’s turmoil; the trial is elsewhere. He sits with a lantern—the workaday light of guards and travelers—and submits to the discipline of remorse. By choosing the aftermath rather than the climax, the painter focuses on what contrition feels like from the inside: the slow, attentive work of facing one’s error.

Composition and the Geometry of Repentance

The composition is a study in stability. A broad triangular mass occupies the right half of the canvas: Peter’s torso, bent head, and clasped hands form a single, weighty volume. On the left, the lantern rests on a stepped table that provides horizontal counterweights. The diagonal from Peter’s eyes to the lamp’s central pane anchors the picture, creating a visual tether between sinner and light. A generous field of darkness occupies the upper right, deepening the sense of enclosure. Nothing crosses the foreground to distract the gaze. Everything funnels toward the relationship that matters—the old man’s attention and the lamp that answers it.

Light as Confession and Consolation

De la Tour’s light is both subject and theology. The lantern’s candle sits in a glass chamber; we see its core flame, its corona of molten air, and the warm reflections that multiply in the panes. That light grazes Peter’s cheekbone, slips across his brow, and catches the knuckles of clasped hands. It leaves other zones in a respectful dusk: the hollow of the eye socket, the fold under the chin, the dark cloth of the robe. Illumination functions like a confessional: it reveals enough to be truthful but not so much that it shames. The candle is not accusatory; it is companionable, a modest presence that allows correction to be borne.

The Face and Hands as the Grammar of Contrition

In de la Tour, faces and hands do the eloquent work that rhetoric would otherwise perform. Peter’s mouth is parted in a tiny oval, the soundless shape of “Lord.” The cheek is drawn slightly inward, as if memory hurts. Most telling are the hands: fingers interlocked, joints prominent, sinews gently flexed. This is not theatrical wringing; it is the plain, habitual clasp of prayer. A single highlight along a knuckle confirms the moistness of tears without displaying them. The painter avoids melodrama and offers instead the recognizable posture of anyone who has sat awake, reckoning, with a small flame for company.

The Lantern as a Moral Instrument

The lantern is rendered with loving exactitude: conical cap, heavy framing, thick panes cloudy with use, the catch of light along the metal ribs, the tiny pool of wax at the candle’s base. It is not a symbol plucked from allegory but a working object. Precisely because it is so practical, it becomes persuasive as metaphor. A lantern is portable, protective, designed to keep a fragile flame alive in wind; so too repentance shelters a spark of truth as a person crosses rough ground. The object’s sturdiness mirrors Peter’s future strength: the same hands that clasp in grief will one day grip the Church’s work with reliability.

Color Harmony and the Temperature of Night

The palette is restricted to soot-rich browns, umbers, and the honeyed yellow of lamplight. Peter’s robe reads as a deep charcoal brown that swallows light and gives back barely a whisper of warmth at the edges. His trousers receive more glow, offering rusted orange planes that echo the candle’s heat. The tabletop and the lantern’s casing take a stronger amber, turning the left half of the painting into a small furnace. Because colors remain within a narrow band, emotion is steady—no cold shock, no garish heat—just the durable warmth of a humble vigil.

Texture and the Truth of Surfaces

De la Tour’s persuasiveness depends on surface truth. Skin is a living matte: the forehead holds a soft sheen where light gathers, and the wrinkles around the eye and at the corner of the mouth take tiny, accurate shadows. The linen at the chest opening lifts a faint highlight; the coarse wool of the robe eats light between its folds; the lantern’s glass carries a muted glare and slight distortions where thickness varies. These material specificities create a world we trust, and into that credibility the artist quietly inserts spiritual meaning. Repentance feels real because everything else does.

Silence, Space, and the Sound of Vigil

The surrounding dark is not empty; it is acoustically charged. There is enough room for the viewer to imagine small sounds: the whisper of a flame, the occasional ping of cooling metal, the old man’s inhale before a prayer resumes. The bench, the table, and the lantern create a modest architecture that holds the vigil without clutter. The economy of props heightens the sense that repentance requires privacy. De la Tour engineers this privacy by giving the figure broad margins of shadow and by banishing anecdote. We are not shown the rooster that triggered tears, because grief has already moved inward.

From Spectacle to Self-Knowledge

Seventeenth-century art often delights in moments of spectacle—trials, martyrdoms, ecstasies. De la Tour chooses self-knowledge instead. His Peter is not caught in the first sting of shame but in the steadier labor of amendment. The painting honors a virtue that rarely attracts crowds: persistence. The lantern will burn as long as oil and wick hold; the old man will sit as long as it takes. Without sermon or inscription, the work proposes that the soul’s great turns happen in rooms like this, at hours like these, with tools as simple as breath and light.

Iconography Held Lightly and Precisely

Traditional attributes of Peter—the keys and the rooster—do not appear here. Their absence is deliberate. The painter invites the viewer to identify the apostle by age, beard, and the theater of remorse rather than by props. This restraint lets the image speak across confessional lines. What we witness could be the repentance of any person acquainted with failure. And yet, for those who know the story, subtle cues abound: the fisherman’s rough hands, the traveler’s lantern suited to a courtyard or guardroom, the forward-thrust head of a man listening for a remembered warning. Iconography becomes a quiet undertone rather than a headline.

A Dialogue with De la Tour’s Other Penitents

The picture converses with de la Tour’s St. Jerome scenes and with his multiple “Repenting Magdalene” canvases. All are built from the same grammar—single light source, large planes, few objects—and all translate theological states into precise domestic actions: reading, contemplating, tending a flame. Compared to Magdalene’s poised introspection, Peter’s posture is rougher and more masculine; compared to Jerome’s scholar’s bench, his surroundings are humbler. Yet the common conclusion is identical: interior change happens when light is stewarded and attention steadies.

Psychology in Profile

By placing Peter in three-quarter profile, de la Tour simultaneously shows and shields him. We see enough of the face to read emotion, but not enough to feel that we intrude. The angle also dramatizes the movement of thought: the head thrusts toward light while the body remains planted in shadow. That physical split—forward-leaning face, seated weight—becomes a psychological diagram of remorse pulling toward amendment while habit still anchors in the old self. The painter does with posture what a preacher might do with words.

Technique, Edges, and Planes

The surface authority of the painting rests on de la Tour’s mastery of edges and planes. The line of the nose is unbroken, its shadow a firm, simple wedge that carves the face into two volumes. The ear is a compact, half-lit shell. Hands are built from large shapes first, then accented with crisp knuckle ridges and small creases. The lantern’s geometry is exact enough to satisfy a joiner: vertical muntins, beveled panes, top vents painted with a single cool highlight. Glazes deepen the background so that darkness breathes rather than suffocates, and thin scumbles warm the tabletop where light scatters. Nothing is hurried; the paint handles quiet like an old friend.

Time and the Present Continuous

De la Tour favors the “present continuous”—a verb tense translated into paint. Peter is praying, not “has prayed” or “will pray.” The candle is burning; wax is pooling; the night is holding; repentance is occurring. The artist avoids narrative cues that would move the scene forward because the point is duration. A person becomes new not through a flash of feeling but through minutes that add up to hours. In this way the painting is about time as much as it is about sorrow: time used well, time guarded from distraction, time given to what matters.

Humanism and the Dignity of Old Age

The old man’s body is not idealized. His cheek slumps slightly; his beard is thin at the chin; the skin of his hands is textured with labor. De la Tour confers dignity on age by showing how experience and remorse can coexist without despair. The painter rejects youthful fervor in favor of seasoned steadiness. That humanism is consistent across his oeuvre—street musicians, readers, household workers—and here it gives Peter’s repentance a texture recognizable to viewers who have grown old with their regrets and hopes intact.

Historical Context and the Consolation of Interior Peace

Painted late in de la Tour’s life, after decades of war and deprivation in Lorraine, the picture’s inwardness reads as a cultural salve. Public life had been loud with conflict; the artist offers an image where peace is assembled from small pieces: a chair, a lamp, a prayer. It is not escape but repair. The scene says, implicitly, that after catastrophe one rebuilt space at a human scale and practiced the habits that make a person trustworthy again. In such a context, Peter’s tears do not shrink him; they put him back to work.

The Ethics of Looking

The viewer’s position is just outside the circle of warmth. We are close enough to see the flame’s architecture and the wet corner of an eye, far enough that our presence will not interrupt the vigil. That respectful distance is a moral instruction. Suffering that leads to amendment deserves witness without voyeurism. De la Tour ensures this by directing Peter’s gaze past us toward the lamp and by letting darkness defend his solitude. We are guests of the light, not owners of the moment.

A Meditation for Modern Rooms

The painting reads cleanly in modern rooms lit by desk lamps and phone screens at three in the morning. Anyone who has kept a wake for worry or remorse recognizes the posture, the silence, the way a small light gathers thoughts and makes them examinable. “Tears of St. Peter” provides a model for such hours: stay; hold the light; let the dark assist concentration; bring hands together and tell the truth; wait until the flame has done its work. The image suggests that contrition is not humiliation but a craft the soul can learn.

Conclusion

“Tears of St. Peter” distills Georges de la Tour’s late genius into a single, lucid vigil. Composition gathers figure and lamp into a geometry of attention; light exposes without shaming; color keeps the room warm and humane; texture persuades the senses; gesture writes the grammar of prayer; silence builds a chamber where self-knowledge can grow. Without rooster or keys, the painting still tells the whole story: a man faces himself, light steadies him, and night becomes a partner in his renewal. Few images describe repentance with such restraint and authority, or make so clear that the smallest, steadiest flame can guide a life back to truth.