Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

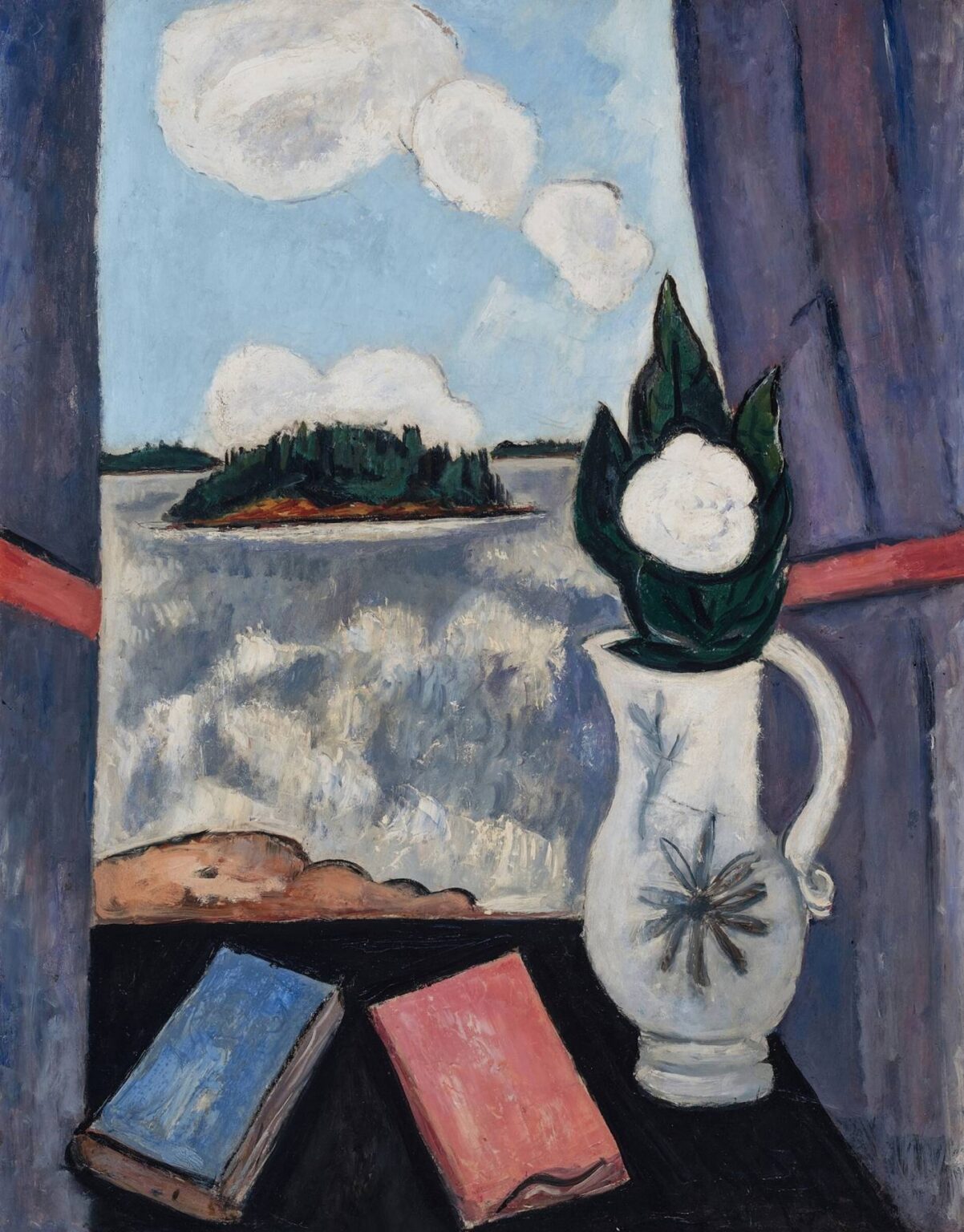

Marsden Hartley’s Summer Sea Window (1940) is a late-career meditation on looking—outward to the luminous waters of coastal Maine and inward to the life of the mind framed by books, flowers, and the intimate stillness of a room. The canvas stages a dialogue between interior and exterior, intellect and sensation, memory and immediacy. A white pitcher holding a single white blossom stands sentinel on a dark tabletop beside two closed books, while beyond the open window an island floats on a rippling, sunstruck sea beneath buoyant clouds. Hartley fuses these elements with bold contours, simplified shapes, and a restrained yet radiant palette, offering a scene that is at once domestic and cosmic. In this extended analysis, the painting’s historical circumstances, formal strategies, symbolic content, and place within American modernism will be explored to reveal how Summer Sea Window crystallizes Hartley’s lifelong pursuit of spiritual clarity through the language of paint.

Hartley in 1940: Return, Resolve, and Reflection

The year 1940 found Hartley settled once more in Maine after years of peripatetic wandering through Europe, New Mexico, Bermuda, and the American West. He had endured personal losses and professional fluctuations, but his return to the Northeast came with a clarified sense of purpose: to become, as he put it, “the painter from Maine.” At the same time, war consumed Europe, and the United States hovered on the brink of entry. In such a climate, the tranquil vantage of a summer window was less escapist than it might appear; it was a deliberate act of rooting oneself in place, of asserting continuity against instability. Hartley’s late works often merge landscape and still life to affirm the enduring structures of perception and the psyche. Summer Sea Window belongs to this cohort, exuding the contemplative calm of a man who has reconciled avant‑garde experimentation with a vernacular, personal modernism anchored in home terrain.

A Window as Stage and Threshold

The window motif has a venerable place in art history, from Renaissance illusions of painted “views” to Matisse’s chromatic portals on the Mediterranean. Hartley deploys the device as a hinge between two realms. The interior foreground, dominated by the tabletop, pitcher, and books, forms a dark plane of intellectual and emotional grounding. The open sash admits a flood of space and light, creating a pictorial axis that draws the eye through the still life toward the island and sky. The window frame itself is barely indicated: two violet curtains and a horizontal red band mark the threshold. This minimal framing emphasizes permeability rather than separation. Hartley invites viewers to oscillate between the tactile presence of objects and the expansive vista beyond, heightening awareness of how perception is structured by the spaces we inhabit.

Compositional Architecture and Rhythmic Balance

The painting’s structure is deceptively simple. The rectangle of the tabletop anchors the lower half, its black surface acting like an abstract field on which the pitcher and books are set. The open window occupies the upper half, filled with sea, sky, and clouds. Yet a closer reading reveals a sophisticated interplay of diagonals and verticals that stabilize and energize the scene simultaneously. The two books tilt at complementary angles, implicitly pointing toward the pitcher, whose curving silhouette rises to meet the verticality of the flower’s leaves. The island outside sits slightly off center, counterbalancing the pitcher’s weight. Cloud clusters ascend the sky in a loose diagonal echoing the books’ tilt. These subtle correspondences weave interior and exterior into a single rhythmic fabric, affirming Hartley’s belief that the world is an integrated, patterned whole when seen with concentrated attention.

Color, Light, and Atmosphere

Hartley’s palette, while restricted, is orchestrated for maximum resonance. The sky is a high, chalky blue mottled with white, suggesting summer’s clear glare softened by haze. The sea takes on a cooler, silvery cast, achieved through layered grays and blues broken by streaks of white, capturing the Atlantic’s surface glitter without naturalistic fuss. The island’s greens are deep and forested, edged with warm earth notes along the shore, a miniature world of solidity amid the mutable waters. Inside, the pitcher glows with pearly whites and subdued grays, its floral ornament rendered as a starburst that mirrors the books’ rectangular blocks of color. One book is blue, the other a salmon pink, hues that bridge the cool outside and the warm interior accents of the curtains. The resulting chromatic conversation suggests that intellect (books), feeling (flower), and nature (island and sea) share a single spectrum of experience.

The Authority of Contour and the Expressive Line

Hartley outlines forms with assertive, dark contours, a signature device dating back to his Berlin period. These lines are not merely descriptive; they confer weight and inevitability on each object. The pitcher’s handle curls like a musical clef, while the leaves of the flower are encased in thick edges that transform them into emblematic shapes rather than botanical specimens. The island’s perimeter is similarly bracketed, holding it fast against the fluid sea. This graphic certainty lends the composition a sense of carved permanence, as if each element were hewn from the same substance. Hartley’s line consolidates form and feeling, granting the everyday tokens of life—books, flower, landmass—the same monumental dignity traditionally reserved for grand historical or religious subjects.

Brushwork and the Material Surface

The surface of Summer Sea Window is alive with varied strokes. In the sea and sky, Hartley uses broken, scumbled applications that allow underlayers to flicker through, suggesting movement and light without resorting to fussy detail. The books and pitcher, by contrast, receive smoother, more solid handling, conveying their tactile immediacy. The curtains’ purplish folds are built from layered strokes that shift subtly between cool and warm violets, giving them both weight and softness. This dialectic—broken vs. smooth, granular vs. polished—encodes the distinction between phenomena in flux and objects at rest, between the ephemeral play of atmosphere and the enduring presence of human artifacts. The paint’s physicality remains evident throughout, reminding viewers that they confront not a window “onto” nature but a crafted object—a painting—through which nature is perceived and re-imagined.

Symbolism of Objects: Books, Pitcher, Flower, and Island

Each item carries metaphorical heft. The books, closed and resting on their covers, imply stored knowledge, contemplation, and the artist’s intellectual life. Their contrasting colors hint at dualities—reason and emotion, past and present, Europe and America—brought into dialogue on the table of Hartley’s consciousness. The white pitcher, a domestic vessel, symbolizes containment and offering; it holds water or flowers, bridging utility and beauty. Its starburst decoration subtly echoes the radiating sun or perhaps a compass rose, suggesting orientation and guidance. The single white blossom, cradled by dark green leaves, evokes purity, renewal, and solitude—a distilled essence of nature brought indoors. Beyond the sill, the island stands as an emblem of isolation and refuge, a recurring motif in Hartley’s Maine paintings. Surrounded by water, it is both cut off and protected, a metaphorical self-portrait of the artist’s independence and interiority.

Interior and Exterior as Psychic Landscape

Hartley often used landscape as a surrogate for internal states. In Summer Sea Window, the interior still life can be read as the mind’s chamber—books as memory, flower as feeling, pitcher as vessel of self—while the exterior seascape represents the world of sensation, time, and flux. The window does not merely separate them; it sutures them. The red band spanning the curtains resembles a ligature, binding inner and outer realms. The cloud procession could be construed as thought balloons, floating outward from the books’ closed covers into the open air. Conversely, the white of the blossom seems to echo the clouds’ whiteness, implying that what blooms inside has its counterpart outside. Hartley thus stages a reciprocal flow: perception shapes inner life, and inner life frames what is seen.

Geometry, Flattening, and Modernist Economy

Despite its recognizable subject matter, the painting is modernist in its reduction and ordering of forms. The tabletop becomes a black trapezoid, the window a pale rectangle, the island an oblong mass capped with a dark scalloped edge of trees. Clouds are schematized into chunky ovals and crescents, their cumulative chain forming a rhythm akin to musical notation. This controlled geometry reins in naturalism, allowing Hartley to stress relationships over verisimilitude. The flattened planes recall Cézanne and early Cubism, yet Hartley retains a warmth and immediacy foreign to analytic cubist dissection. The economy of means—few objects, simplified shapes, restrained color—demonstrates a confidence born of decades mastering what to leave out so that what remains can resonate fully.

The Maine Coast and American Identity

Hartley’s self-fashioned role as “painter from Maine” was not parochial posturing but an ideological stance. At a time when American art sought to define itself apart from European dominance, Hartley’s landscapes and interiors rooted in Maine asserted a regional modernism, as cosmopolitan in sensibility as it was local in subject. The island in Summer Sea Window is distinctly of the North Atlantic, with its dark conifers and rugged outline. The light is not Mediterranean but New England—cool, sharp, slightly melancholy even in summer. By embedding a still life of books and domestic ware into this coastal view, Hartley suggests that American culture is nourished both by land and literature, by solitary study and communal geography. The painting, then, participates in the larger national project of articulating a modern vision without abandoning local specificity.

Echoes of Earlier Works and Anticipations of Late Motifs

The vocabulary seen here—pitchers, flowers, simplified clouds, black tabletops—appears elsewhere in Hartley’s oeuvre. His still lifes of the 1910s and 1920s often featured floral arrangements isolated against dark grounds. His New Mexico canvases flattened landforms into biomorphic masses under elaborated skies. In the 1940s, he repeatedly painted islands, coves, and storms off the Maine coast, granting them mythic stature. Summer Sea Window gathers these threads: it is an interior still life, a landscape, and a symbolic abstraction all at once. The dark table anticipates the somber tonalities of his final works, while the spirited clouds forecast the expressive gesturalism edging into postwar American painting. In compressing a lifetime of motifs into a single, coherent statement, the painting reads like a visual autobiography in code.

Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions

There is a quiet intensity to Summer Sea Window, a sense of prayerful pause. The closed books intimate a moment after reading, when ideas settle. The single flower, freshly cut, suggests a present-tense tenderness, perhaps even a memorial. The island under a procession of clouds evokes the passage of time, each cloud a discrete moment drifting by. Hartley, who had experienced profound personal losses, often wove elegiac notes into his work. Yet this painting is not mournful; it is poised, contemplative, hopeful. The window’s open expanse implies openness to the world’s beauty. The starburst on the pitcher feels like a sun held indoors, a reminder that light can be housed within. In this synthesis, Hartley articulates a spiritual stance: the sanctity of ordinary things, the interconnectedness of interior reflection and external wonder.

The Painting’s Legacy within American Modernism

Summer Sea Window exemplifies how American modernists adapted European innovations without relinquishing narrative or emotive content. Hartley’s contemporaries in the 1940s ranged from the precisionists’ machine-age clarity to the burgeoning abstract expressionists’ gestural bravura. Hartley carved a middle path, employing simplified shape and bold contour while never abandoning subject matter. His influence resonates in later artists who explored windows and thresholds—Fairfield Porter’s domestic Maine scenes, Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series, even contemporary painters who revisit the still life as a site of metaphysical inquiry. The painting’s balance of formal rigor and emotional availability models an approach to modernism that is neither coldly formalist nor sentimentally descriptive, but integrative and humane.

Conclusion

Summer Sea Window is a distilled vision of Hartley’s artistic creed: that the ordinary can be made extraordinary through attentive seeing, that landscape and still life can speak to one another in the language of form, and that the self finds its measure between the pages of books and the sweep of the sea. The painting’s controlled composition, resonant color, authoritative line, and symbolic economy coalesce into an image that feels inevitable, as though it could exist only in this configuration. In the calm dialogue between a white flower in a pitcher and an island under clouds, Hartley offers an image of balance—between solitude and connection, knowledge and sensation, interiority and the wide world. As viewers, we are invited to sit at this table, open the window in our own perception, and let sea, sky, and thought intermingle.