Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions

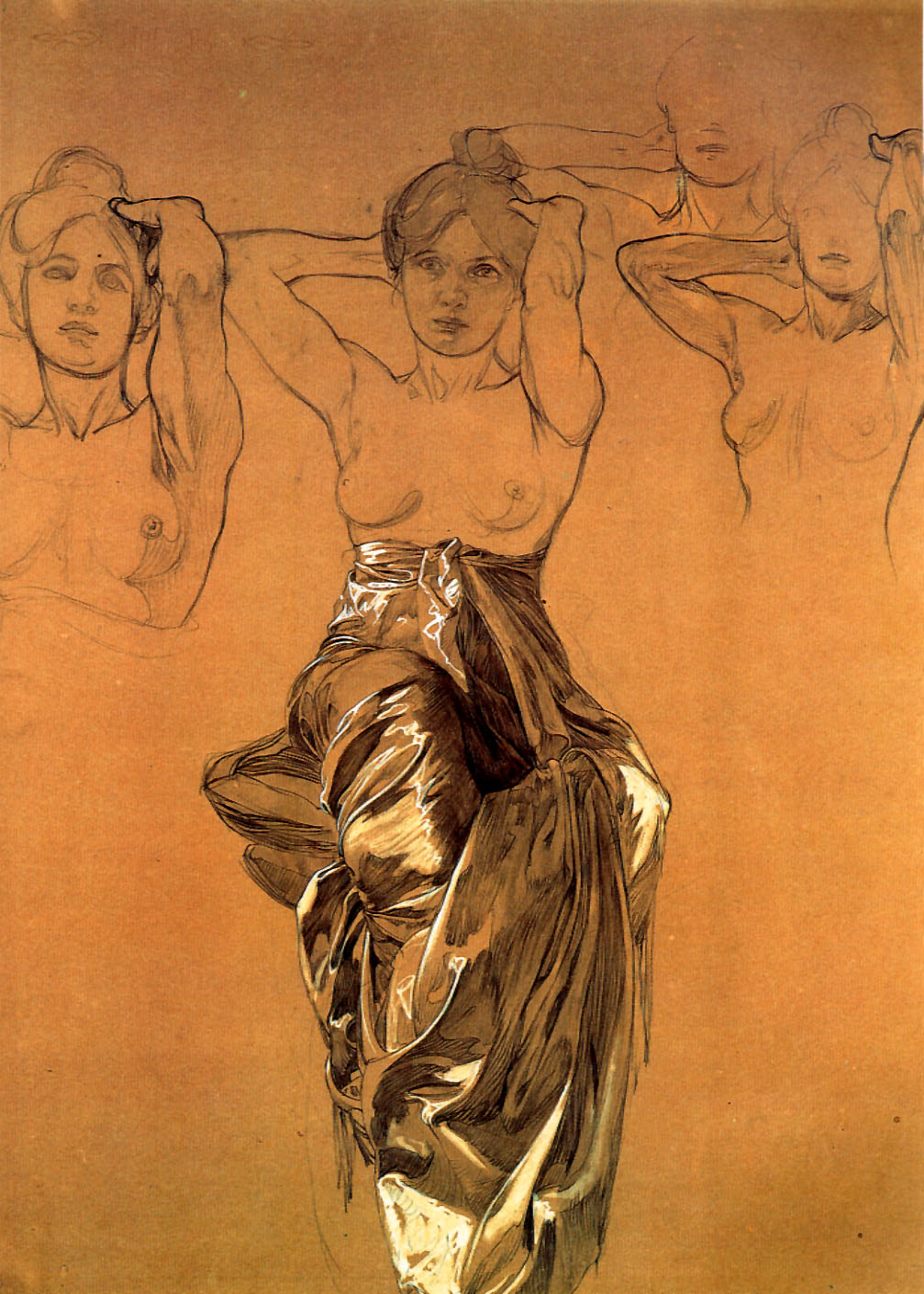

Alphonse Mucha’s “Study of Drapery” (1900) is a working sheet that feels both intimate and authoritative. On warm, tan paper, three nude female torsos with raised arms appear across the upper half like successive thoughts. Only the central head is brought to a fuller finish, its gaze steady and frontal. Below, a single body unfurls into an opulent cascade of fabric wrapped around the hips and legs. The cloth is the true protagonist: it twists and pools in gleaming folds rendered with quick, dark contours and assertive strokes of white heightening. The page reads like the moment when an idea crosses from anatomy into costume, from living pose into the ornamental language that would animate Mucha’s decorative panels.

Historical Moment

By 1900 Mucha had already reshaped Parisian visual culture with his theater posters and decorative series. Yet the refinement of those public images depended on private sheets like this one. The artist was trained within the academic tradition, where drapery studies were a discipline unto themselves, and he carried that discipline into his Art Nouveau idiom. This drawing belongs to the period when he consolidated the figure type that would recur in cycles devoted to the seasons, the arts, gemstones, flowers, and times of day. The raised-arm pose appears across his oeuvre, and the handling of cloth here—silky, weighty, rhythmically divided into long S-curves—clarifies how he could translate the weight of fabric into the abstract music of line.

Purpose Of The Study

The sheet is not a portrait and not yet a composition; it is a workshop problem set. Mucha tests how a torso with lifted arms will look from slightly different angles, how the neck rotates, how the deltoids stretch, how the clavicles read when the head shifts. At the same time, he works out a specific drapery system for the lower body: how to knot the cloth at the waist, where to let it billow, how to stage the big folds that catch highlight. The study isolates the variables that a later finished work must harmonize. In that sense, it preserves the artist’s thinking more candidly than any polished lithograph can.

Materials And Method

The drawing is executed on toned paper that supplies a ready-made midtone. Over this ground Mucha builds form with a dark medium—charcoal or soft graphite—for contours and shadows, then strikes sparkles of white chalk to model sheen. The technique is classical and efficient. Because the paper already sits between light and dark, the artist can “pull” the lights forward with white and “push” the depths back with the dark line, achieving volume without laborious hatching. The white is decisive rather than timid; it lands on the highest planes of the satin, the knotted sash, and a few anatomical accents. The entire page is a lesson in how to make a surface glimmer with just two pencils and a warm sheet.

Composition Across The Page

Three bust-length studies across the top create a quiet rhythm from left to right—fuller on the left, most complete at center, then retreating into a ghosted outline at right. Below, the massed drapery anchors the page like a sculptural plinth. The eye moves first to the central face—because it is the most developed—and then drops into the deep valley of folds. Those folds descend diagonally, then curl back in a counter-sweep, keeping the movement lively. The overall geometry is triangular: apex at the head, breadth at the billowing hem. This simple arrangement gives the exploratory sheet unexpected poise.

The Raised-Arm Motif

Mucha returns again and again to figures with hands lifted to the hair or behind the head. The gesture elongates the torso, opens the chest, and sets up long diagonals that he can weave with ribbons, flowers, or sashes. Here the motif is examined for structure rather than ornament. The acromion notch, the stretch across the pectoral arch, and the compression above the ribcage are all indicated with economical lines. Because the arms are up, the waist can carry a dramatic knot of fabric without occluding the anatomy, a relationship that would prove essential in his panels where the garment is as expressive as the pose.

Drapery As Architecture

The cloth is rendered like built form. Mucha lays out primary folds—the load-bearing curves—then subdivides them into secondary ripples and tertiary flickers of highlight. He thinks like an architect of fabric, deciding where weight gathers, where tension tugs, and where slack pools. The knot at the waist is not merely decorative; it is a mechanism that redirects gravity, sending one long lappet forward into light and another backward into shade. Highlights ride the crests like reflections on hammered metal, declaring a satin or silk surface that magnifies the play of light. This is drapery not as filler but as a protagonist capable of carrying the mood of an image.

Light, Sheen, And Material Illusion

On toned paper, white chalk becomes light itself. Mucha deploys it in assertive swathes to simulate the specular gleam of smooth fabric. Notice how he avoids smearing the white; he lets it sit crisp on the paper so that edges sparkle. Where the cloth turns away, he withholds the white and lets the brown ground breathe through, creating the soft warmth of shadow without heavy darkening. The result is a convincing illusion of lustrous material that seems to shift under the studio lamp. One can almost feel the cool slip of satin across skin.

Anatomy And Economy

Although the study is devoted to cloth, the underlying anatomy is carefully judged. The sternum line, the soft modeling of the breasts, the notch of the suprasternal fossa, and the slope of the trapezius are all noted with restraint. Mucha never labors these forms; he states them once and lets the viewer complete the solidity. The heads at left and right are reduced to contour and a few shadow accents, a reminder that in preparatory work the artist apportions finish according to need. The economy is instructive: when the drapery must carry brilliant detail, the body can remain simple without losing authority.

From Study To Decorative Panel

Sheets like this are the seedbed for Mucha’s large cycles. A viewer familiar with works such as “Brightness of Day,” “Dance,” or many of the floral personifications will recognize the raised arms, the cinched sash, and the serpentine fall of fabric. In a finished lithograph, these folds would be translated into flat color shapes contained by a decisive outline, but their logic would be the same as on this page. The study therefore demonstrates the hidden bridge between life drawing and the stylized clarity required by printing. The glamorous panels owe their credibility to this patient rehearsal of weight and light.

The Dialogue With Tradition

Mucha’s drapery practice converses with an older lineage. Renaissance and academic workshops trained artists to drape models in real cloth and draw the fall of folds for days before touching the figure. Drapery offered a laboratory for light and form because fabric multiplies planes and edges. In this sheet one can hear distant echoes of Leonardo’s chalk studies or the nineteenth-century écorché-and-drapery exercises of the academies. What Mucha adds is the Art Nouveau sensibility: the folds are engineered not just to mimic nature but to produce the long, musical curves that underpin his decorative style.

Rhythm And Musicality Of Line

The success of the sheet depends on rhythm. Broad arcs swing down the left side of the skirt, then tighten into quick zigzags where cloth bunches near the knee. The knot provides a percussive accent before the line relaxes again. These alternations—slow/fast, tight/loose—create a musical structure. Even the ghosted head studies participate, repeating the beat of the raised arms like a motif stated and varied. Mucha’s greatness lies in this translation of physical facts into visual music. Drapery is the instrument; line is the melody.

Negative Space And Breath

The vast, unworked areas of the paper are not empty; they are breath. Mucha leaves the background untouched so the viewer can feel air around the figure and cloth. The tan ground also warms the drawing, preventing the white chalk from becoming clinical. Around the upper studies, those reserves of space keep the page from crowding, allowing each pose to ring like a separate note. The generosity of the margins—especially above the heads—emphasizes the upward lift of the arms and the vertical ambition of the central figure.

Process Traces And the Artist’s Hand

Look closely and you can see hesitations, redrawings, and adjustments. A contour thickens where he corrects a shoulder. A highlight is dragged once, then reinforced. A half-erased line lingers at a hip, a ghost of an earlier idea. These traces are not blemishes; they are the narrative of making. They show how Mucha solved the problem in real time—testing a fold, rejecting it, finding a better path for light. For scholars and admirers alike, these marks are precious because they expose the confident, searching hand behind the polished public image.

Theatricality Without Narrative

Mucha’s figures often carry the gravity of theater without telling a story. This sheet is no different. The lifted arms, cinched waist, and billowing skirt suggest a moment of arrangement before a performance or ritual, yet no anecdote is supplied. That refusal lets the forms communicate directly, free from illustrative duty. In his finished works, that same approach allows the viewer to project mood and meaning into the figure without being confined by plot. The study is an anatomy of poise rather than a fragment of tale.

The Intelligence Of Edges

Edges carry enormous meaning here. Where the fabric turns toward the light, the edge may be a crisp dark line kissed by a white stroke; where it turns away, the edge may dissolve into the paper. Mucha varies the sharpness of edges to control depth and attention. The knot receives the sharpest contrasts—appropriate for the visual and mechanical center—while the outer hems soften, letting the cloth blend into air. This edge intelligence is what later allows his printed panels to remain legible at a distance; he knows exactly which divisions are structural and which can be lost without harm.

Relationship To Ornament And Pattern

Once the big folds are established, they can host ornament: embroidery, borders, or floral chains. Even when no pattern is drawn, the folds themselves act as ornament, generating repeating shapes that could be echoed elsewhere in a design. Mucha understood that drapery could supply an entire panel’s decorative rhythm without adding a single extra motif. This study proves the point. The page looks complete even though there is no background pattern or frame; the cloth’s architecture is decoration enough.

Emotional Temperature

For all its technical intent, the sheet carries a quiet emotion. The central face is alert, almost solemn, and the sheen of fabric feels ceremonial. There is no coyness in the nudity; it is a studio fact and an aesthetic premise. The viewer senses concentration—the model holding a pose, the artist solving light. That concentrated calm is the emotional foundation of many Mucha images. Beauty, in his hands, is crafted equilibrium rather than overstimulation.

Why This Study Matters

“Study of Drapery” makes visible the scaffolding of Mucha’s celebrated style. It shows that the glamour of his posters rests on rigor, that the flowing lines are anchored in observation, and that the poise of his women is built fold by fold, edge by edge. For anyone interested in how decorative art achieves authority, the sheet is invaluable. It demonstrates how to turn matter—cloth under gravity—into form that can bear symbolism and delight.

Conclusion

On a single sheet of warm paper, Alphonse Mucha rehearses the partnership between body and garment that would define his art. Three exploratory busts fix the pose; a tour-de-force of satin folds announces the stagecraft of light. Dark contour and white heightening collaborate to make fabric breathe, knot, and gleam. The drawing is both a record of problem solving and a finished meditation on form. Through it we meet the maker behind the myth, the craftsman whose discipline made his elegance inevitable.