Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: A Singular Moment Captured in Oil

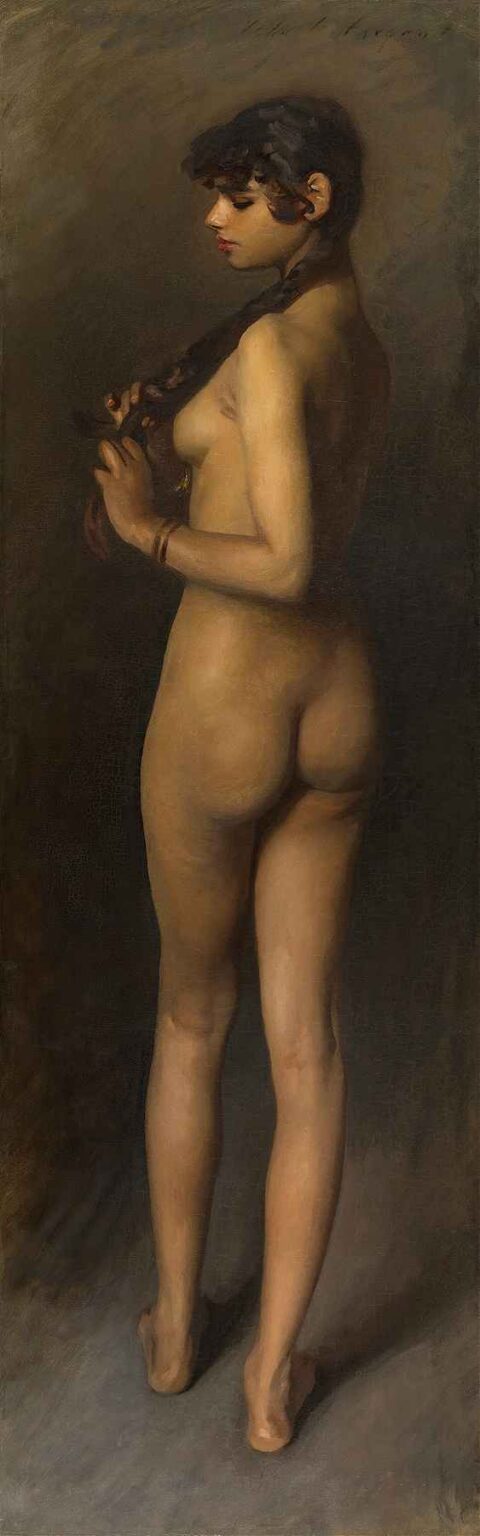

John Singer Sargent’s Study of an Egyptian Girl (1891) stands as a testament to his extraordinary ability to fuse academic discipline with a painterly freedom that still feels remarkably modern. Painted during his travels in the eastern Mediterranean, this life study depicts a young woman of Egyptian descent in a moment of private preparation. Stripped of narrative embellishment or elaborate setting, the work offers a direct encounter with the human form—softly illuminated, subtly modeled, and poised between classicism and Impressionism. This analysis will explore how Sargent’s compositional choices, handling of light and shadow, and brushwork coalesce into a powerful study of presence, identity, and artistic mastery.

Historical and Cultural Context: Sargent in the Near East

In 1890–1891, Sargent embarked on a transformative journey through Spain, North Africa, and the Near East. Fascinated by the region’s peoples and landscapes, he made numerous sketches and studies that broadened his artistic vocabulary. Study of an Egyptian Girl emerges from this period of exploration. At a time when Orientalist painting was rife with romanticized and often stereotyped portrayals, Sargent approached his subjects with respect and sensitivity. Rather than exoticizing his sitter, he recorded her with quiet dignity, emphasizing shared humanity over sensationalism. This nuanced approach set him apart from many contemporaries and indicated a deeper cultural curiosity grounded in observation rather than fantasy.

Composition and Framing: A Vertical Emblem of Intimacy

The painting’s vertical format echoes the elongated proportions of the human figure and reinforces its sculptural quality. Sargent situates the girl centrally, her back turned toward the viewer, which creates a sense of privacy and invitation simultaneously. The narrow framing excludes any extraneous detail—no furnishings, no architectural elements—allowing the figure to occupy the pictorial space entirely. The modest crop at the ankles and just above the head emphasizes the body’s uninterrupted flow, guiding the viewer’s gaze along the sinuous curves of her spine, waist, and hips. This compositional economy underscores the work’s status as a study: an intimate, unmediated investigation of form.

The Power of Silence: Absence of Narrative Detail

Unlike many Orientalist works of the era, Study of an Egyptian Girl contains no anecdotal props or superficial indicators of setting. There are no ornate carpets, no veils, no Moorish arches—only a neutral, mottled background that recedes into shadow. This silence heightens our focus on the sitter’s corporeal presence and the act she performs: braiding her long, dark hair. By stripping away narrative trappings, Sargent invites contemplation of universal themes—beauty, ritual, identity—rather than the tired tropes of Orientalist spectacle. The result is both timeless and timely, bridging academic tradition with a modern insistence on authenticity.

Depiction of the Body: From Surface to Substance

Sargent’s rendering of flesh is at once sensuous and restrained. He captures the supple flesh of the shoulders, the subtle tension of muscles beneath the skin, and the gentle roundness of hips and buttocks with remarkable fidelity. Yet he never lapses into over-detail. Instead, he lets broad, soft transitions between light and shadow model the figure. The left leg remains largely in shadow, receding into the neutral ground, while the right leg—and the buttock above—catches a delicate light that reveals form without anatomical fussiness. This balance of specificity and suggestion allows the viewer’s eye to complete the figure, fostering engagement rather than passive consumption.

Light and Shadow: Sculpting Form with Chiaroscuro

Chiaroscuro—the interplay of light and dark—serves as the backbone of this study. A soft, diffuse illumination falls from the viewer’s left, gently outlining the contours of the back, shoulder blade, and the swell of the buttock. The transitions are so gradual that the flesh seems to glow from within. Meanwhile, the darkest shadows at the spine and the left side of the torso ground the figure and add weight. Sargent’s mastery lies in calibrating these tones to convey both volume and atmosphere. The neutral background, painted in warm grays and browns, supports the figure’s form without competing for attention, enhancing the illusion that the sitter emerges from—and dissolves back into—the painterly space.

The Gesture of Hair: Ritual and Identity

At the core of the composition is the sitter’s action: she braids her hair. This simple, almost mundane gesture becomes a focal ritual, laden with symbolism. Hair braiding is an act of feminine self-fashioning—an intimate practice combining practicality and aesthetic care. Sargent captures the tension in her fingers as they guide strands of hair, the slight turn of her head as she concentrates. The long plait cascades down her back, interrupting the smooth plane of flesh with a rhythmic repetition of light and dark. This interplay between body and braid accentuates her individuality: she is not a generic “Oriental” figure but a real person engaged in a universally understandable act of self-presentation.

Brushwork and Painterly Economy: Suggestion Over Exhaustion

A closer look at the surface reveals Sargent’s economy of means. He applies paint in thin, fluid layers for skin areas, allowing the ground to shine through and animate the flesh. In contrast, the hair receives more assertive, linear strokes, capturing both texture and movement. The background is created with broad, loose sweeps, with visible brush marks that lend vitality to what might otherwise be a flat void. This contrast between controlled modeling on the body and spontaneous passages around it enhances the figure’s central presence. Sargent’s brushmanship never calls attention to itself; instead, it serves the higher purpose of animating form and evoking an atmosphere of contemplative intimacy.

Color Palette: Restraint and Resonance

The painting’s palette is deliberately muted: a harmonious blend of warm browns, subdued ochres, and soft grays, punctuated by the deeper browns of the hair and the warmer flesh tones. There are no jarring accents, no overt chromatic spectacle. This restraint underscores the work’s introspective quality. The warmth of the palette conveys a sense of human touch and natural light, while the tonal harmony unifies figure and ground. Even the highlights—on the shoulder, the plait, the gentle curvature of the thigh—are subdued, avoiding specular glare in favor of a softly diffused glow. Such tonal consistency ensures that the figure remains the exclusive locus of attention.

Spatial Ambiguity: Figure Emerging from the Void

Without architectural landmarks or furniture, the sitter inhabits an indeterminate space. This spatial ambiguity heightens the sense that she emerges from—and might recede back into—a world of paint and possibility. There is no horizon line, no suggestion of floor or wall beyond the immediate floor plane under her feet. The neutral background functions as an atmospheric field, echoing the contours of the body through mottled tonal shifts. This approach dissolves the boundary between subject and space, making the figure seem both present and ephemeral—a vision conjured by paint rather than a physical being fixed in a defined locale.

Psychological Presence: Quiet Confidence and Poise

Despite her back-turned position, the sitter radiates a compelling inner life. The slight inclination of her head suggests concentration and self-awareness. Her shoulders are relaxed, her weight balanced, conveying both ease and stability. The act of braiding implies self-care and personal ritual rather than performance for an external gaze. This inward focus generates a sense of quiet confidence: she is comfortable in her body and in this painterly encounter. Sargent’s decision to withhold facial detail amplifies this effect, inviting viewers to project their own interpretations while acknowledging the sitter’s autonomy.

Orientalism Reconsidered: Respectful Observation

Orientalist painting in the 19th century often exoticized non-Western subjects, reducing them to decorative motifs or sexual fantasies. Sargent’s Study of an Egyptian Girl transcends these clichés through its respectful, empathetic approach. He avoids the lurid colors and titillating poses common in orientalist tropes, instead emphasizing naturalism and individual presence. The study functions less as an exotic curiosity and more as a universal celebration of the human form. In doing so, Sargent both participates in and quietly critiques the orientalist tradition, offering a nuanced portrayal grounded in genuine observation rather than manufactured spectacle.

Academic Roots and Modern Innovations

Trained in Paris under Carolus-Duran, Sargent inherited an academic foundation in life drawing and classical form. Yet he embraced the freer brushwork of the Impressionists and the atmospheric qualities of the Barbizon School. Study of an Egyptian Girl exemplifies this synthesis: the anatomical precision of her proportions reflects academic discipline, while the looseness of the background and the visible brush marks reveal a modern sensibility. The painting becomes a bridge between two worlds—honoring tradition while venturing into new territory. This dual allegiance explains Sargent’s enduring appeal to both conservative and avant-garde audiences of his time.

Legacy and Influence: A Model of Empathy in Portraiture

Study of an Egyptian Girl has influenced generations of artists interested in the ethics of representation. By privileging empathetic observation over exotic spectacle, Sargent models a form of portraiture that respects cultural difference while highlighting shared humanity. The painting’s focus on a simple, unadorned gesture—braiding hair—resonates with contemporary concerns about agency, identity, and the politics of the gaze. In academic settings, it serves as a benchmark for instruction in figure painting, demonstrating how economy of means can yield profound emotional and formal depth.

Conclusion: An Enduring Study of Form and Self

John Singer Sargent’s Study of an Egyptian Girl stands as a masterclass in portrait and figure painting. Through its harmonious composition, nuanced lighting, and painterly economy, the work transcends its era, offering a timeless reflection on form, ritual, and identity. The enigmatic presence of the young woman—captured mid-braid—invites ongoing dialogue about cultural encounter, the ethics of representation, and the universal language of human gesture. More than a mere academic exercise, this study remains a poignant testament to Sargent’s ability to see—and to make us see—the profound poetry in the everyday act of self-adornment.