Image source: wikiart.org

An attic room where modern color and solitude meet

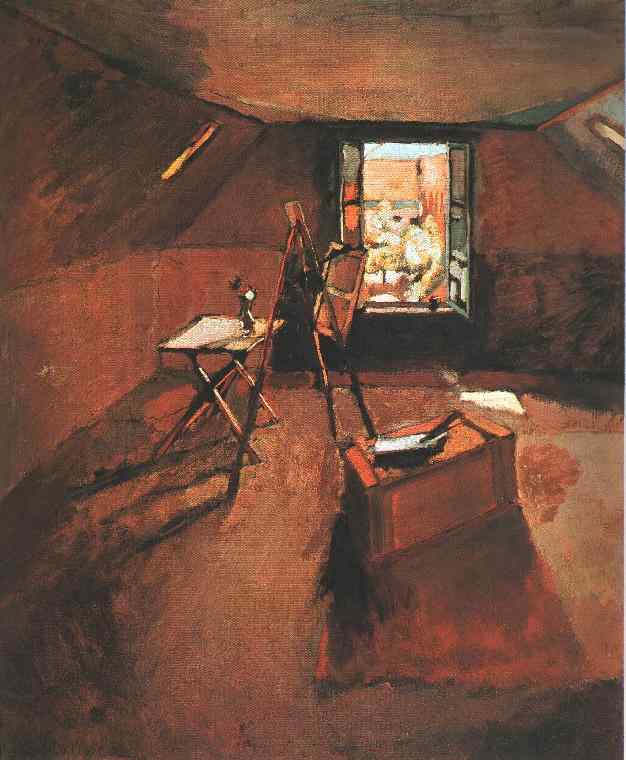

Painted in 1903, “Studio under the Eaves” finds Henri Matisse at a crossroads. The artist has not yet detonated the blazing chords of Fauvism, but he has already shifted away from academic description toward an architecture of color, simplified mass, and candid brushwork. The subject is intimate and autobiographical: a cramped garret studio, sparsely furnished, where an easel leans toward a bright window that punches a luminous opening into an otherwise earthen world. In this quiet interior Matisse rehearses many of the strategies that will power his later breakthroughs—tilted planes that privilege the surface, color that does structural work, and a compositional rhythm that makes emptiness speak.

What the painting shows and how it reads at first glance

The room is a low attic under pitched roofs. Its slanting walls drive the gaze toward a small central window, shutters ajar, through which a sunlit cluster of roofs, bricks, and sky flashes in cool light. A foldable table stands to the left with a bottle or small vase on top; a ladder-like easel occupies the space before the window; a wooden chest or bench sits to the right, its lid supporting papers or a sketchbook. Long, raking shadows stretch across the floor. Except for the window’s cold burst of blue-white, the entire space is built from red-browns, umbers, and terra-cottas. The effect is both austere and theatrical: a stage set for the artist’s labor where light and color, rather than people, play the lead roles.

Composition: slanting planes, a luminous rectangle, and a triangle of work

Matisse draws the viewer into the room with a geometry that is simple and compelling. The pitched ceiling and the two eaves form a dark tent that funnels the eye toward the window—an emphatic, near-square opening that acts as a vanishing point and a light source. Within that funnel a triangle of “work” anchors the composition: the small table at left, the easel at center, and the chest at right. Their legs and edges rhyme, creating a web of diagonals that echo the rafters above. The objects are modest in scale, but the shadows they cast extend their presence and link them across the floor. The broad, empty expanse of the floor—brushed in warm earth hues—serves as the painting’s vast middle register, a canvas within the canvas on which light performs.

Space held shallow by the pull of the surface

Although linear perspective leads to the window, Matisse never lets the room dissolve into deep illusion. The large, flat planes of wall and floor are treated as fields of color first, surfaces second, recession third. Brushwork runs laterally across those planes, knitting them to the picture plane. The window, brightest and coolest element, is also emphatically a painted rectangle; it both opens and asserts itself as a patch of color. This balancing of real space and decorative surface—of room and tapestry—is one of the hallmarks of Matisse’s interiors and a crucial step toward his mature language.

The color architecture: earthen warmth opposed by a cool aperture

The palette is economical and purposeful. Most of the room is built from burnt sienna, red ochre, raw umber, and iron-oxide reds, lifted here and there by ochre highlights and soot-dark accents. Against this warm continuum Matisse stages a single, decisive cool: the window’s square of pale sky and sunstruck masonry, with hints of blue, green, and chalky gray. That opposition energizes the whole picture. The warm world of interior labor presses toward the surface; the cool beyond recedes. Rather than use black-and-white contrasts to structure the space, Matisse lets temperature do the heavy lifting. The eye reads depth because cool retreats from warm and because color families are kept coherent within their zones.

Light as climate and narrative

Light enters as a steady atmosphere rather than a spotlight. It appears to fall from the window and perhaps from a small skylight above, sliding across the floor in long diagonals. Matisse avoids theatrical glare; highlights on the furniture are warm and restrained, as if filtered by dust and the reddish walls. This evenness of light allows color to remain saturated and keeps the room’s calm intact. At the same time, the illuminated rectangle at center performs a narrative function: it suggests the wider city and daylight that the painter, sequestered in his attic, both longs for and controls. The painting becomes a meditation on choice—between the world outside and the world constructed inside with pigment and time.

Brushwork: candid, economical, and varied across materials

The painting is full of touch. On the big planes—the floor and the left wall—Matisse lets the brush travel in broad, slightly dry strokes that leave the canvas grain visible, creating a matte, breathy surface like worn plaster. On the easel and furniture the strokes are denser and more directional, following legs and edges, turning form with quick changes in value rather than fine modeling. At the window we sense faster, brighter dabs that state sunlight hitting masonry, a looser handwriting that stands out against the steadier room. These shifts of touch give each material a tangible difference while preserving unity: the entire painting feels made of the same hand, the same time of day, the same air.

Drawing by adjacency and the selective role of line

Matisse hardly uses outline. The chest’s lid exists because a dark flank meets a lighter top; the tripod table turns because a warm ochre edge abuts a cooler shadow; the easel is a few firm uprights whose edges are defined by what surrounds them. When he needs to lock a form in place, he allows a dark seam to pass along a leg or under a tabletop, like a stitch that keeps fabric from fraying. This chromatic drawing produces forms that are solid yet breathable and prevents the room from hardening into an academic schematic.

Emptiness as subject and structure

One of the painting’s boldest decisions is its devotion to emptiness. The floor occupies an outsized portion of the canvas; the ceiling and walls are vast, unadorned planes. That bareness is not poverty of invention but a thematic and structural choice. It gives scale to the modest objects, lets interior light travel, and enacts the solitude of work. The long, reddish floor becomes a field where time accumulates—the kind of emptiness acquainted with concentration, punctuated by the noises of distant streets that float in through the open window.

The studio as self-portrait without a figure

Matisse loves the studio as both subject and metaphor, and this garret is a self-portrait by other means. The easel at the center, tipped toward the light, is the painter’s proxy. The chair-like table to the left seems ready to support a still-life arrangement; the papers on the chest suggest studies in progress. The tiny bottle provides a vertical counterpoint and a promise of a future subject. Nothing is precious; everything is useful. The room’s oblique geometry and restricted palette tell us about discipline and patience—the habits by which a body of work is built.

Connections to contemporaneous works and influences

“Studio under the Eaves” converses with Matisse’s other interiors from 1903, such as “Studio Interior,” and with still lifes like “Still Life with a Checked Tablecloth.” In those canvases he also negotiates between planar pattern and palpable space, between the pleasure of color and the clarity of structure. The debt to Cézanne is evident in the weight of forms and the refusal to hide process behind slick finish. The dark warmth and attic melancholy recall certain Dutch and 19th-century French garret scenes, yet Matisse replaces anecdote with distilled relations. He is less interested in storytelling than in the logic of color and the ethics of looking.

The window: a picture within the picture

The open casement is both literal and pictorial. It depicts a view, but it also behaves as an inset painting, a cool-toned composition whose frame is built into the room’s wall. This picture-within-a-picture tethers the interior to an exterior world without letting the latter dominate. That interplay would become a lifelong device for Matisse—the use of windows and mirrors to multiply space while honoring the flatness of the canvas. Here, the device is still modest, but it already produces a sophisticated tension: if you stare into the window too long, the room’s warm surface pulls you back.

Psychological climate: quiet resolve rather than drama

Despite the starkness of the setting, nothing feels anxious. The warmth of the palette bathes the space in a calm glow. The furniture is simple and sturdy. Shadows lengthen but do not threaten. The painting’s mood is one of concentrated resolve, the everyday heroism of showing up to work. Matisse’s touch, steady and unhurried, reinforces that mood. It is a room where effort becomes habit and habit becomes style.

Likely palette and material decisions

While only technical examination can confirm, the harmony suggests a practical, earth-friendly kit: lead white for lights; yellow ochre and raw sienna to warm surfaces; burnt sienna and Venetian red to bring the earthen red of the floor and walls; raw and burnt umber for structuring darks; a trace of ivory black for the deepest seams; ultramarine and cobalt for the window’s cool lights; perhaps terre verte or viridian sparingly to key certain exterior or shadow notes. Much of the paint appears thinned and scumbled, especially on the walls and ceiling, allowing the weave of the canvas to participate in the image. Thicker touches stand at the edges of objects and within the small highlights, giving sparkle and relief.

How to look slowly and fruitfully

A rewarding way to experience the painting is to let your eyes enter from the floor’s foreground and walk toward the window, following the shadows’ diagonal sweep. Pause at the triangle of studio tools, feeling how the table, easel, and chest triangulate the space and carry the weight of the composition. Then let the cool light in the window refresh your vision before returning to the warm field that surrounds it. Step closer to notice the surface’s variety—thin scumbles, loaded edges, dry-brushed patches that leave the canvas grain breathing. Step back and notice that the entire room clicks into a few large relations: warm world, cool opening; emptiness, tools; slanting envelope, upright easel.

From attic quiet to chromatic audacity

Seen from the vantage of Matisse’s later work, “Studio under the Eaves” reads like a disciplined rehearsal for future extravagance. The artist is learning how to rely on color temperature for structure, how to calibrate the amount of information a viewer needs, how to let empty space speak eloquently, and how to keep a painting’s parts subordinated to the whole. When the wild color of 1905 arrives, these lessons will keep his canvases legible and poised. The attic’s restraint is thus not a limitation but a source of authority.

Display considerations that enhance the work

Because the painting lives on subtle temperature contrasts within a largely warm register, it shines under soft, neutral light. Over-warm illumination will push the reds too far and flatten the cool of the window; overly cold light can deaden the earthen glow. A viewing distance that allows the window’s rectangle and the floor’s broad field to be taken in at once helps the composition’s big moves register before the smaller textures invite closer inspection.

Why this painting still matters

“Studio under the Eaves” persists because it dignifies both process and place. The garret is neither romanticized nor pitied; it is understood as a vessel for concentration, a space tuned by color to receive the day’s work. The picture is modest in subject and radical in means—proof that modernism is not only a matter of bright palettes and exotic scenes but also of clarity, restraint, and the decision to let color and structure carry meaning. Many painters have paid homage to their studios; few have made emptiness feel this alive.