Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Weimar Germany and Late Expressionism

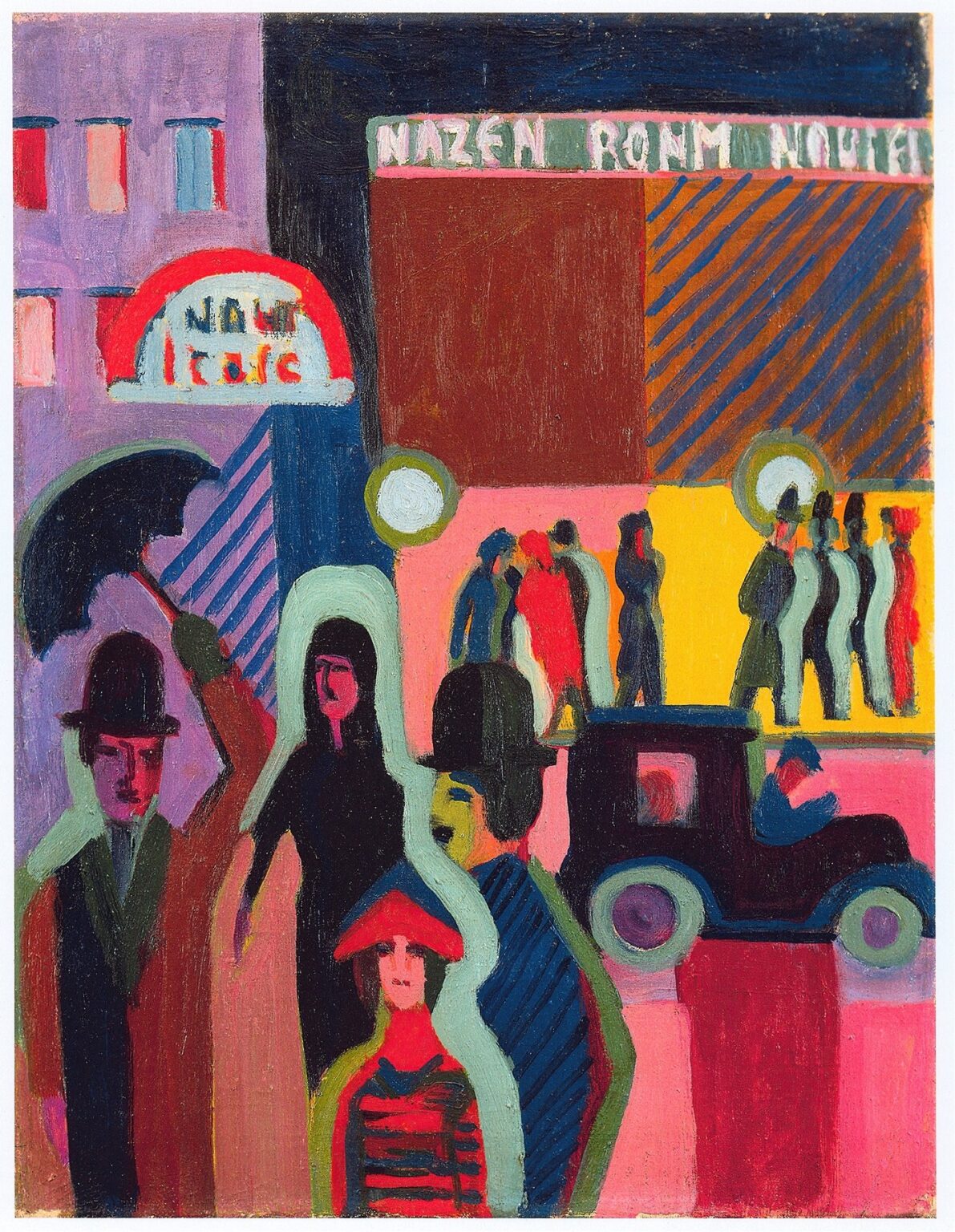

By 1927, the Weimar Republic was in cultural flux. Political turmoil and economic instability coexisted with a dazzling ferment in the arts, film, and design. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938), a founding member of the Die Brücke movement, had already witnessed World War I’s devastation and sought refuge in the Swiss Alps. Yet even in exile, he remained intimately connected to Berlin’s pulsating modernity. His earlier bohemian canvases—raw portraits of dancers, prostitutes, and street scenes—evolved after the war into compositions marked by sharper edges, flatter planes, and an embrace of modern urban iconography. Store in the Rain emerges from this late Expressionist phase, reflecting both Kirchner’s fascination with neon-lit storefronts and his ongoing anxiety about mechanized society.

Kirchner’s Late Style: From Die Brücke Beginnings to 1927 Innovations

Kirchner’s early Die Brücke works (1905–1913) celebrated spontaneous gesture and vibrant color, often applied in thick impasto. After the war, his palette darkened, brushstrokes sharpened, and compositions flattened. By the mid-1920s, Kirchner experimented with simplified forms and graphic patterning influenced by advertising signage and urban typography. In Store in the Rain, he abandons deep perspectival space for broad stripes of color that echo the signage itself. Human figures, once modeled with visceral flesh tones, now appear as schematic silhouettes outlined in acid green or cadmium orange. This stylistic evolution underscores Kirchner’s ongoing response to modern life—not as nostalgic romanticism but as a heightened sensory experience shaped by neon, asphalt, and steel.

Urban Modernity and the Rain-Soaked Street

Rain features prominently in modernist literature and painting as a symbol of alienation, reflection, and the inexorable march of progress. In Store in the Rain, the slick pavement becomes a reflective surface that doubles signage and silhouettes, suggesting the seductive lure of consumer culture and the washed-out anonymity of city dwellers. Kirchner’s flattened reflections, rendered in angular brushwork, make the street itself a character in the drama, emphasizing the tension between individuals and the commercial environments they inhabit. The viewer senses both the magnetism of the brightly lit store and the emotional detachment of figures who traverse it with bowed heads and bowed umbrellas.

Composition: Flattened Space and Graphic Pattern

Kirchner organizes the canvas into interlocking rectangular and diagonal zones of color. The top third bears bold signage—letters silhouetted against green and pink bands—while the lower two-thirds shift between deep navy, mud brown, and blazing pink. Diagonal stripes at right echo the rain’s angle, unifying background and foreground. Human figures appear as near-geometric cutouts, their outlines painted in contrasting hues to ensure legibility against the busy backdrop. This flattened, collage-like arrangement draws on woodcut aesthetics and sports a visual rhythm akin to advertising posters—an apt reflection of Kirchner’s fascination with urban media.

Color and Light: Neon Glow in Oil Paint

Kirchner’s daring palette fuses industrial neons with bruised Expressionist pigments. The signage’s electrified green seems almost iridescent against the dark canvas, achieved through a base layer of cadmium yellow under a fluorescent green glaze. The red arc above the storefront, recalling a half-sun motif, is equally vivid, its glow intensified by surrounding fields of muted purple and black. Figures outlined in chartreuse or pale aqua cut across this chromatic tapestry, their edges shimmering like wet asphalt. Through these color contrasts, Kirchner captures the tension between synthetic light sources and the natural gloom of rainy streets, making neon appear both inviting and disorienting.

Human Presence: Anonymity and Alienation

The figures in Store in the Rain are rendered without individualized features. Hats cast deep shadows over faces; coats collar high; bodies reduced to essential volumes. This generalization intensifies the sense of anonymity, underscoring modernity’s flattening of personal identity. A man raising an umbrella at left tilts his head toward the shop, yet his expression remains inscrutable. A small group at right clusters like mannequins on a display platform, unmoving and detached. Even as they share the same space, each figure occupies a solitary emotional state, their solitude amplified by the painting’s formal austerity. Kirchner thus offers a poignant commentary on urban life’s paradox: constant proximity to others coupled with profound social isolation.

Signage and Text as Visual Elements

The partially legible neon signage—perhaps reading “Nixen” or “Nazen”—serves dual functions. Literally, it identifies the storefront; metaphorically, it becomes part of the painting’s visual vocabulary. Kirchner transforms letters into linear motifs, their blocky forms echoing the figure outlines. By cropping and distorting the text, he mirrors the fractured experience of reading neon signs through rain-streaked spectacles. The illegibility also reflects the linguistic breakdown of a society inundated with advertising—a visual overload where meaning dissolves into color and shape.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Unlike thick impasto of his early Expressionist years, Store in the Rain employs a more varied textural approach. The wet pavement is suggested through thin, near-transparent washes that allow underpainting to flicker through. Signage areas feature dense, opaque strokes for maximum luminosity. Human silhouettes use mid-weight, slightly loosened brushwork, lending them a ghost-like presence. At close range, one notices visible diagonal strokes in the striped background—a reminder of the artist’s hand and the painting’s constructed nature. This interplay of brushwork styles reinforces the contrast between static signage, dynamic rainfall, and spectral passersby.

Psychological Impact: Modern Angst and Visual Overload

Kirchner’s Store in the Rain evokes the psychological dissonance of late-Weimar urban life. Rain becomes an amplifying medium for light reflections and emotional disquiet. The relentless neon glow hints at consumerism’s ceaseless demand, while the crowd’s stony silhouettes convey resignation. There is no center of solace; even the storefront—usually a destination—feels detached behind its glass. Kirchner translates this modern angst into formal terms: flattened space, fractured perspective, and fluorescent color. The result is a sensory barrage that unsettles as much as it attracts, mirroring the era’s social anxieties.

Relation to Contemporary Movements

While Kirchner’s late works share affinities with early Pop Art’s engagement with signage and advertising, they remain rooted in Expressionist subjectivity. Unlike the cool detachment of Constructivism or the abstraction of Bauhaus, Store in the Rain preserves a visceral human presence—even if cloaked in anonymity. His flattening of space parallels artists like Henri Matisse, yet Kirchner retains a darker emotional tenor. The painting also prefigures street photography’s candid gaze on urban life, decades before Cartier-Bresson. In this sense, Kirchner stands at a crossroads between dying 19th-century Expressionism and the pictorial languages that would dominate the 20th century.

Technical Analysis: Materials and Conservation

Technical studies show Kirchner used commercially prepared oil colours common in the 1920s, including cadmium pigments for high-chroma neons. Infrared reflectography reveals an underdrawing of swift charcoal lines, indicating a loosely sketched composition before colour application. As the painting has aged, some fluorescent pigments have faded, prompting careful conservation. Modern restorers employ UV-filtered lighting and stable synthetic varnishes to prevent further degradation of sensitive greens and reds. The painting’s current state offers a glimpse of its original intensity while reminding us of the challenges in preserving high-chroma Expressionist works.

Provenance and Exhibition History

Store in the Rain first appeared in a 1927 Berlin gallery show of Kirchner’s Swiss period paintings. After passing through private German collections, it entered a major European museum’s holdings in the 1960s. It has since featured prominently in retrospectives on German Expressionism and Weimar culture. Exhibition catalogues often highlight it as emblematic of Kirchner’s late urban subject matter—contrasting sharply with his Alpine landscapes and nude studies. Scholarship on the painting continues to deepen our understanding of Kirchner’s adaptation to modern city life and his pioneering use of neon-evoking pigment.

Legacy and Contemporary Resonance

More than ninety years after its execution, Store in the Rain endures as a powerful meditation on urban modernity. Its flattened forms and saturated color anticipate many postwar and contemporary explorations of cityscapes—from Pop Art’s billboard critiques to Neo-Expressionism’s emotional reengagement with painting. In an age of Instagram neon filters and digital signage, Kirchner’s work reminds us that the tension between consumer spectacle and human solitude is nothing new. Gallery visitors today still find themselves drawn into the painting’s eerie glow, recognizing the familiar rush of storefronts and the solitary figures moving through rain-slicked streets.