Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

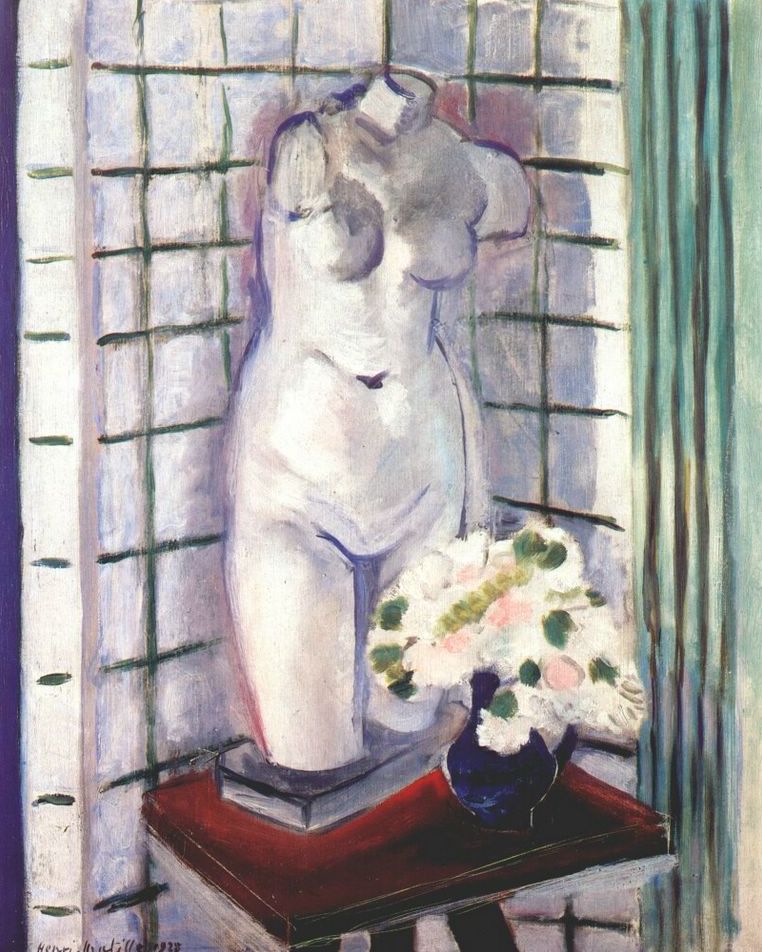

Henri Matisse’s “Still Life with Plaster Torso” from 1928 is a compact studio drama in which a headless classical fragment, a gridded screen, a bouquet of soft blossoms, and a sharply angled table are composed so that color and contour do the thinking. Where many of Matisse’s Nice-period interiors overflow with textiles and odalisques, this canvas pares the stage to a few protagonists. The cool, milky body of the cast stands before a pale green lattice; a midnight blue vase of white and blush flowers gathers light at the lower right; the tabletop, a dark rhombus with carmine highlights, slices across the foreground. Everything is shallow, frontal, and lucid. The painting is a meditation on how the modern surface can host both classical memory and contemporary rhythm.

The Nice Studio As Laboratory

The Nice years gave Matisse a private theater of screens, props, and movable furniture that he could recombine at will. In this picture the laboratory is reduced to essentials: a plaster torso used for teaching and study, a folding screen articulated as a tiled grid, a striped curtain that narrows the right edge, and the table that carries both cast and bouquet. By limiting the cast of objects, Matisse clarifies the purpose of the exercise. He is not describing a room; he is testing relations among calibrated planes, temperatures, and edges until an equilibrium is reached that feels inevitable.

Classical Fragment And Modern Surface

The central object—the fragmentary female torso—summons the authority of antiquity. Yet Matisse refuses illusionism. The cast is not nestled in deep space; it floats against a screen that reads as a set of squares, each sketched by brisk strokes that thicken and thin. The statue’s volume is built by chromatic shifts rather than by heavy chiaroscuro: lilac and slate collect in the underarms and along the ribcage; cool green reflects from the screen; warm pink rises at the hip and breast where the surface turns toward us. The sculpture is at once solid and permeated by the room’s color, a classical memory kept alive on a modern plane.

Composition As A System Of Crossed Vectors

The composition turns on two axes. A vertical runs through the center of the torso and drops to the bouquet; a diagonal begins at the table’s left edge, climbs through the cast’s left hip, and continues to the absent head. These vectors are locked by perpendiculars in the gridded screen and by the crisp front edge of the table. The bouquet sits slightly off-center, a counterweight of rounded forms that plays against the statue’s muscular planes. The screen’s squares slow the background into a measured beat, while the table’s diamond thrust counters that beat with active force. The whole feels like a hinge, each part holding the others in poised relation.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

The palette is intentionally restrained: cool greens and blue-greens in the screen and side curtain; violets, grays, and milk-white in the cast; deep wine and near-black in the table’s top; midnight blue in the vase; feathery whites and pale roses in the flowers. Rather than dazzle with saturation, Matisse pursues clarity. The green lattice cools the room like shade; the table’s red-black chord anchors the foreground and sends warmth up into the torso’s modeling; the bouquet condenses the full temperature range in miniature, with lemony lights, pinks, and deep leaf greens held in a small, singing cluster. Because hues borrow from their neighbors—the torso inhaling green along one flank, the blossoms catching violet shadow from the cast—the color feels like a climate rather than a set of separate notes.

Pattern, Grid, And The Discipline Of Looking

The screen’s grid is not background wallpaper; it is a metrical device that organizes attention. Its lines are hand-drawn, sometimes doubled, often scumbled so that canvas tooth breathes between strokes. This keeps the grid alive and stops the eye from sliding off the surface. The squares also declare the modernity of the space: the antique torso is not returned to a period setting but brought forward onto a contemporary scaffold where intervals can be measured. The grid is the picture’s chessboard—an implicit metaphor for Matisse’s method of spacing differences until they cooperate.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s line gives the painting its authority. The torso is carved by responsive edges that tighten over the shoulder stump, breathe across the belly, and flex again around the hip. The bouquet’s leaves are written in swift, calligraphic touches, some dark to secure a silhouette, others pale to suggest light passing through a petal. The table’s facets are set with decisive breaks—one clean tilt in the front plane, another along the far edge—to keep geometry crisp without hardening it into diagram. Everywhere the edge is a living seam, not a prison, allowing color to press gently against its neighbor.

Light, Shadow, And The Kindness Of Diffusion

Nice light is ambient and even, and Matisse relies on that diffusion to keep values moderate. Shadows are chromatic, not black: lilac in the hollows of the cast, bluish gray where the torso faces away from the window, olive on the side nearest the curtain. Highlights are precise and small—the cool ridge at the left breast, the thin gleam on the vase’s shoulder, the soft white on a petal—distributed so the eye can travel without glare. Because the value range is calm, color carries the volume; because light is kind, each thing can share air with the others.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Depth is shallow by design. The screen behaves like a pinned tapestry just behind the objects; the table functions as a shelf thrust toward the viewer; the curtain compresses the right margin into a vertical band. Overlaps do the persuasive work—the torso’s base over the table, the bouquet before the cast’s thigh—but perspective otherwise recedes. This productive flatness keeps attention where Matisse wants it: at the surface, where edges meet and temperatures negotiate, where the modern painting lives.

The Bouquet As Counterpart And Timekeeper

The flowers serve several duties at once. As a form, the bouquet’s cloud of soft circles counterbalances the statue’s planar anatomy, humanizing the scene without sentimentality. As a color instrument, it concentrates whites and pale pinks that echo the cast yet remain alive and vegetal, and it injects deep greens that tether the lower half to the screen’s lattice. As a temporal sign, it suggests the living present beside the timeless cast. The painting is not a museum vitrine; it is a studio, a place where perishable blossoms and plaster study share a day’s light.

The Table As Stage And Structural Bass

The table is the painting’s bass note. Its dark planes and sharp angles provide weight at the bottom edge and keep the lighter top from floating. The slight scarlet glints around the perimeter energize the mass without breaking its authority. The rhomboid tilt points into space just enough to seat the torso solidly, and the bevels act like stagecraft, clarifying how objects claim their positions. Without this measured heaviness, the grid and the white cast would risk becoming airy and disembodied.

Classical Memory And Modern Agency

By placing a classical fragment on a modern set, Matisse engineers a conversation about what lasts in art. The torso stands for the persistent force of the human figure reduced to essentials; the grid and the angled table assert the painter’s agency here and now. The bouquet mediates between the two. This triangulation lets the painting honor tradition while insisting on the present tense of surface, touch, and color. Rather than nostalgia, the picture offers contemporaneity that knows its ancestors.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

The canvas behaves like a chamber piece in a restrained key. The grid sustains a steady pulse; the torso’s curves introduce long phrases that crest at shoulder, hip, and thigh; the bouquet supplies trills and grace notes; the table’s bass holds the harmony. The eye’s melody begins at the high light of the left breast, flows down the abdominal curve to the bouquet’s whites, moves across the blue vase and up the table’s far edge, then returns via the screen’s scaffolding to the cast’s shadowed flank. On each circuit new correspondences appear: a green note in the cast answering a stripe in the curtain, a violet in a petal echoing the shaded sternum, a red edge of the tabletop softly warming the cast’s lower contour. The painting rewards repeated listening.

Materials And The Intelligence Of Touch

Matisse differentiates substance through touch as much as through color. Plaster is rendered with creamy strokes that knit into a skin-like surface; glass is thinner, layered, reflective; petals are laid with dry, feathery touches; the table receives denser, more opaque paint to project solidity. The grid lines are dragged and sometimes broken, admitting the weave of the canvas, which, in turn, keeps the whole alive as a painting rather than an illusion. This sensitivity to material keeps the scene persuasive while protecting the primacy of the painted surface.

Evidence Of Process And The Earned Harmony

Close looking reveals small restatements that make the serenity credible. A softened contour along the hip shows where the edge was moved to settle the figure onto the table; a cooled square behind the shoulder keeps the headless stump from merging with the screen; the red accent at the table’s corner is reinforced to lock the foreground; a petal is brightened to reacquire rhythm with the statue’s highlight. These traces testify to tuning. Harmony here is achieved phrase by phrase.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

The mood is attentive and calm. There is no anecdote, no theatrical spotlight; instead, a climate where the eye can dwell. The headless torso avoids the pull of portrait psychology and allows viewers to attend to relations rather than to identity. The bouquet brings warmth without sentiment; the grid offers order without tyranny. For the viewer the experience is meditative: tracing seams, testing temperatures, revisiting the hinge where a violet shadow meets a green square and seeing anew how the painting keeps its balance.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

This canvas speaks to several neighbors in Matisse’s practice. It converses with the gridded interiors of 1928 where tiled walls steady reclining figures, except here the grid addresses a statue, not a live model, sharpening the theme of art about art. It recalls earlier studio still lifes—compotiers, lemons, vases—by substituting a sculptural cast for fruit and staging a more austere set of planes. At the same time, the large, flat units and interlocking contours anticipate the simplified logic of the late paper cut-outs, in which color shapes meet at declarative seams.

Why The Painting Endures

“Still Life with Plaster Torso” endures because it turns restraint into richness. With a handful of elements—a cast, a bouquet, a grid, and a table—Matisse composes a world of relations that continues to yield discoveries. The painting’s satisfactions are structural and renewable: the curve that answers a square, the cool that quiets a warm, the heavy plane that lets a white glow. It offers an image of thinking through looking, an art that respects the past while insisting on the present tense of color and touch.

Conclusion

Matisse’s 1928 still life is a lesson in clarity. The classical fragment, the measured grid, the living bouquet, and the angular table are not props but actors in a lucid play where color operates as architecture and contour as breath. Depth is shallow, light is kind, pattern is disciplined, and every decision is tuned to let differences cooperate. The result is a studio image that feels both intimate and monumental, an emblem of how modern painting can honor tradition while speaking in the language of the surface.