Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context of 1927

The year 1927 sat squarely between the upheaval of World War I and the looming specter of the economic and political crises that would climax in 1929. In Weimar Germany, a fragile democratic experiment fostered remarkable cultural ferment: cabaret, cinema, theater, and the visual arts all vied to express the contradictions of modern life. Against this backdrop, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, co-founder of the radical Die Brücke movement in 1905, had by the mid-1920s established a studio in Davos, Switzerland. Here the alpine air and verdant valleys offered both refuge from urban anxieties and new pictorial possibilities. Still Life with Orchids (1927) owes its existence to this dual inheritance: it channels the bold Expressionist legacy of Kirchner’s early years, while also embracing the formal concision and chromatic restraint he developed in his Swiss exile. In this period, still life became for Kirchner a laboratory for color, form, and psychological resonance, allowing him to explore internal states through deceptively simple arrangements of objects.

The Artist’s Mature Still-Life Practice

By 1927, Kirchner’s still lifes had evolved from frenetic experiments in color contrast to carefully balanced compositions suffused with lyrical understatement. His early post-war works often juxtaposed urban detritus—bottle shards, broken glass, newspaper fragments—to comment on societal fragmentation. In Davos, however, he found in flowers, pottery, and household objects subjects that spoke to renewal, domestic calm, and the restorative rhythms of nature. Still Life with Orchids represents the apex of this late-style development: the orchid, a flower long associated with exoticism and refined beauty, becomes the centerpiece of an elemental pictorial statement. Rather than demanding narrative interpretation, Kirchner here invites viewers to contemplate the interplay of line, hue, and surface, trusting that emotional impact will emerge from formal harmony rather than overt symbolic coding.

Composition and Spatial Structure

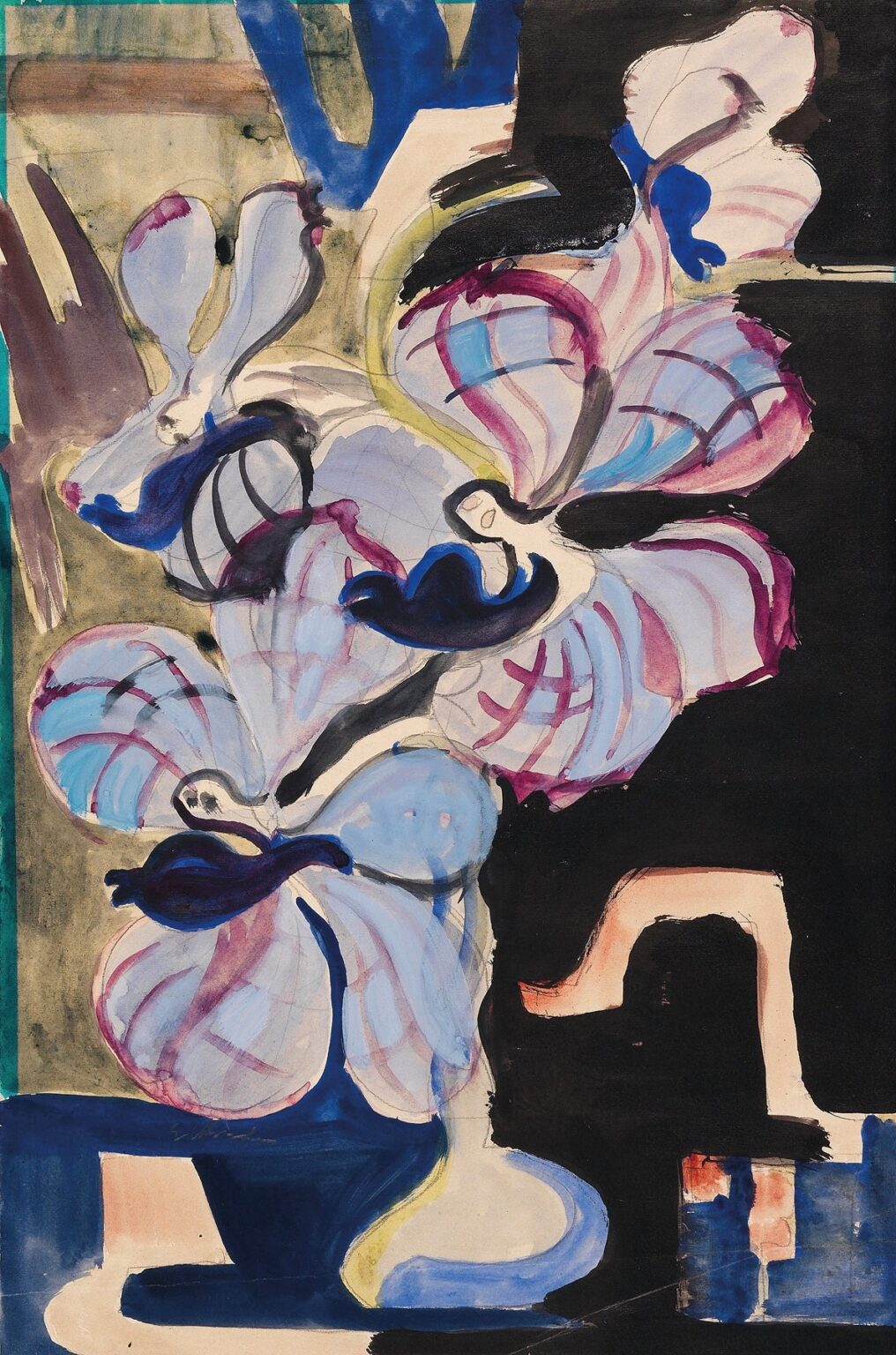

At first glance, the canvas presents a flourish of oversized orchid blooms dominating its upper two-thirds, their undulating petals forming arcs that both frame and challenge the viewer’s gaze. Beneath them sits a simplified vase rendered in deep ultramarine and soft ivory, cut off at the base by the painting’s lower edge. The background divides into contrasting zones: a warm, olive-hued field on the left and a planar jet-black field on the right. This stark dichotomy compresses depth, flattening foreground and background into a single pictorial plane. Kirchner’s choice to bisect the canvas vertically—half in light, half in darkness—establishes a dynamic tension between presence and void. Yet the orchids’ organic curves bridge this divide, uniting the composition into a cohesive whole.

Color Palette and Emotional Undertones

Kirchner’s palette in Still Life with Orchids balances restrained hues with strategic brightness. The flowers themselves display soft lilac and pale blue washes, overlaid with energetic strokes of fuchsia and maroon that trace petal veins. These cooler tones sit against the warmth of the olive background, whose ochre undertones hint at earthiness and latent sunlight. The vase’s deep blue provides an anchoring counterweight to the blossoms’ lightness—a visual echo of alpine skies mirrored in ground-bound flora. Finally, the black field introduces a note of gravity, suggesting shadow, mystery, or perhaps the unconscious. This interplay of complementary and contrasting colors evokes a quietly charged atmosphere: beauty emerges amid ambiguity, and serenity coexists with undercurrents of tension.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Kirchner’s handling of paint here demonstrates his command of varied techniques to evoke both solidity and airiness. The orchid petals bear thin, translucent washes that allow underlayers of pencil-drawn grid lines to glimmer faintly, lending them a diaphanous quality. Over these, he applies pulsing arcs of heavier pigment—often with a loaded brush directly out of the tube—to map veins and petal edges. The olive background shows broader, more diffuse strokes, suggesting an absence of strict control and inviting the viewer’s eye to roam. In contrast, the black field is a dense curtain of matte color, applied in broad, decisive sweeps that mask any underdrawing. This juxtaposition of delicate and emphatic brushwork echoes the orchids’ dual nature—as ephemeral flowers and as potent symbols of endurance.

Iconography and Symbolic Resonance

While Kirchner’s still lifes rarely carry overt allegorical messages, the orchid in 1920s Europe held layered connotations. Exotic and difficult to cultivate, orchids symbolized both high refinement and the perilous margins of nature. In post-war society, they could suggest a yearning for beauty that transcended mundane reality or, alternatively, a caution against overindulgence in luxury amid hardship. In Still Life with Orchids, however, the flowers seem to speak more personally: their arching forms and interlocking petals evoke the human body in stylized embrace, hinting at themes of connection, fragility, and longing. By isolating them against a stark background, Kirchner strips away contextual cues, allowing the orchids’ formal resonance to generate meaning—beauty as assertion of life force above the void.

Relationship to Expressionist Principles

Expressionism prized the projection of inner experience onto external forms, often through bold distortion and color. Though Still Life with Orchids exhibits a more measured restraint than Kirchner’s street scenes of the 1910s, the work nevertheless embodies core Expressionist values. The orchids’ exaggerated scale and rhythm of line transform them from botanical specimens into emotive forms. The flat fields of color disregard optical realism, reaffirming that painting’s primary task is not mimicry but the articulation of feeling. Moreover, the stark contrast between light and dark fields recalls the movement’s fascination with dichotomies—joy and despair, vitality and silence. In this sense, Kirchner extends Expressionism’s legacy: he channels subjective intensity into formal harmony rather than compositional shock.

Technical Materials and Methodology

Scientific analysis of Kirchner’s late still lifes reveals his materials and layering strategies. The support is a medium-grade linen, primed with a thin layer of white gesso that allows for subtle underpainting sketches. Infrared reflectography shows a loose pencil grid underlying the orchid’s petal geometry, indicating careful preliminary composition. Pigment analysis identifies synthetic ultramarine in the vase, lead-tin yellows in the olive field, and modern aniline dyes in the fuchsia highlights—evidence of Kirchner’s willingness to experiment with newly available materials. The black field, by contrast, employs a traditional carbon pigment, suggesting a deliberate contrast between time-tested and avant-garde colorants. The painting’s preservation, with only minimal craquelure confined to thicker impasto areas, attests to both Kirchner’s material knowledge and careful stewardship by subsequent custodians.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After its completion in 1927, Still Life with Orchids entered a private collection in Zurich, avoiding the cultural purges of the 1930s that targeted avant-garde art. It was first exhibited publicly in a 1930 Kirchner retrospective at the Kunstmuseum Davos, where critics noted its poised elegance amid more turbulent works. The painting later traveled to Berlin and London exhibitions in the 1950s, helping to rehabilitate Kirchner’s reputation post–World War II. Today, it resides in a major European museum’s permanent collection, often highlighted in shows examining the evolution of Expressionist still life. Its exhibition trajectory underscores the work’s resilience—both as an object that survived political upheaval and as a visual statement that continues to engage contemporary audiences.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Early reactions to Kirchner’s mid-1920s still lifes were mixed: some critics admired their formal ingenuity and emotional depth, while others yearned for the rawer intensity of his pre-war output. By the late 20th century, however, scholars recognized works like Still Life with Orchids as key to understanding Kirchner’s mature vision—how he channeled Expressionist fervor into compositions that balanced introspection with painterly bravura. Contemporary art historians often cite this painting as a precursor to mid-century abstract still lifes, tracing lines from its flattened space and color fields to later movements. Moreover, its nuanced interplay of form and atmosphere has inspired modern floral painters and interdisciplinary artists investigating the emotional resonance of botanical imagery.

Personal Engagement and Viewer Experience

Encountering Still Life with Orchids invites a contemplative pause. The orchids’ graceful curves draw the eye in languid loops, while the vase’s solidity offers a moment of visual rest. The split background—half luminous, half opaque—provokes reflection on presence and absence, light and shadow. Viewers often report a heightened awareness of the painting’s surface textures: the gentle ridges of impasto on petal edges, the velvety flatness of the black field, the faint pencil grid glimpsed beneath washes. This sensory richness fosters an intimate dialogue: one feels both the orchid’s ephemeral beauty and Kirchner’s confident hand. In this way, the painting transcends still-life convention to become an immersive meditation on form’s capacity to mirror feeling.