Image source: wikiart.org

First Look: An Intimate Theater of Everyday Things

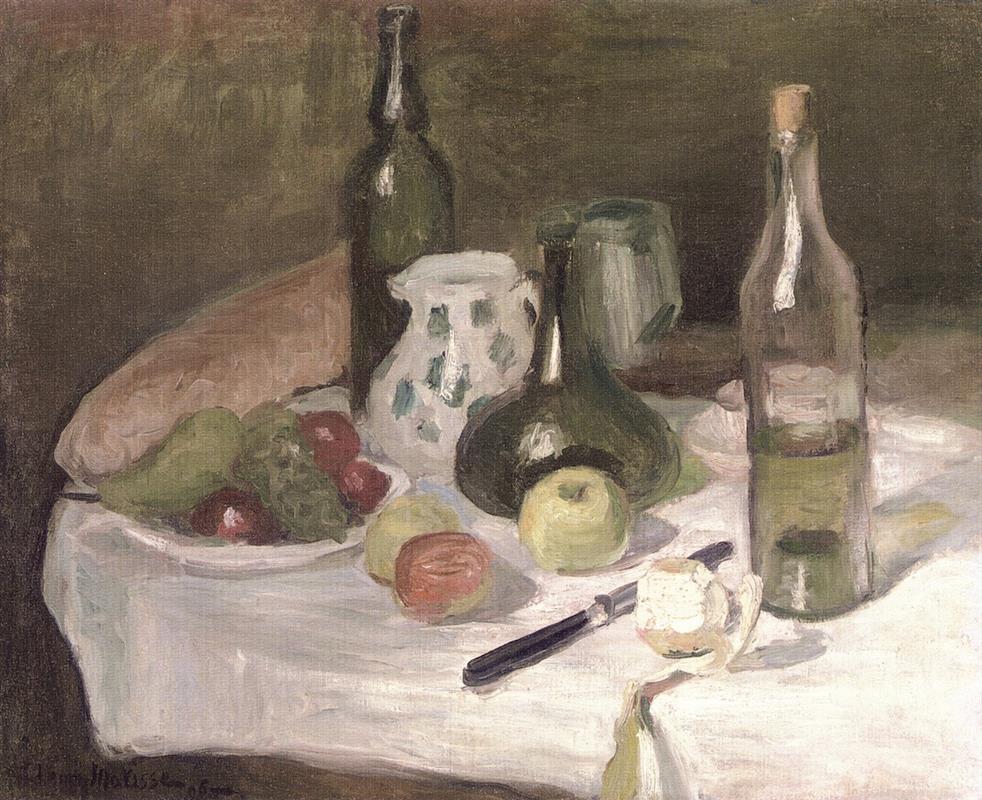

Henri Matisse’s “Still Life with Fruit and Bottles” from 1896 stages a quiet drama on a tabletop. A white cloth becomes the luminous proscenium for bread, apples, a pear, a curling lemon peel, a knife, a patterned jug, a metal pot and several green bottles—one tall and corked, one squat and round, and another half-hidden. The palette is restrained, with olive greens, umbers, grays, and soft whites setting a contemplative tone. Yet the picture is anything but inert. With subtle shifts of temperature and value, and with edges that alternate between crisp and dissolved, Matisse animates each object so it participates in a balanced, breathing whole. The scene feels domestic and unforced, a study of things near at hand painted with the seriousness he reserved for grand subjects.

What the Eye Encounters and How It Moves

The composition is triangular. The tall bottle on the right forms one vertex, the bread loaf and dark bottle at left the second, and the cluster of low fruits and the squat carafe at center the third. The table itself tilts gently toward us, its front edge described by the bright cloth, so that the arrangement occupies a shallow stage set against a deep brown backdrop. The eye lands first on the light-struck cloth and the peeled lemon near the front edge, then crosses diagonally through the knife to the central carafe and fruit, pauses at the spotted jug, and finally climbs the verticals of the bottles. The rhythm of rounded forms—apples, pear, bottle bellies, the jug’s mouth—pulls the gaze in loops that keep attention circulating within the frame.

The White Tablecloth as a Source of Light

Matisse lets the white cloth act like a light source rather than a neutral support. Its surface is built from cool and warm whites, blue-grays, and grazing strokes that suggest folds without fussing over them. In places he scrapes the brush thin so the weave of the canvas whispers through, and elsewhere he leaves ridges of pigment that catch the studio light just as a thick linen would. The cloth’s high key contrasts strongly with the deep wall behind, establishing a value structure that holds the ensemble together. That same cloth unfurls toward the viewer, inviting us to reach across the edge as if to touch the lemon or steady the knife.

Bottles as Vertical Counterweights

The glass bottles are compositional anchors. The tall, corked bottle on the right, with its interior band of greenish liquid and soft, fogged reflections, nails the composition to the picture plane. Its silhouette is carefully calibrated: assertive enough to counter the table’s diagonal but not so dark as to dominate. The central, gourd-shaped carafe introduces a compact mass whose rounded belly echoes the nearby apples. And the darker bottle at left, partially veiled by bread, extends the rhythm into the background, connecting foreground and deep space. Matisse paints reflections with a few economical strokes, letting mere suggestions of highlights do the work of describing glass.

Bread, Fruit, and the Everyday Sublime

Food in Matisse’s early still lifes is never just pantry inventory. The loaf of bread tucked into the left corner stabilizes the composition like a warm, earth-colored wedge. The fruit—two apples, a pear, perhaps a lemon—offers a range of volumes from firm sphere to teardrop. He models them with muted reds and apple greens, shifting hue rather than plunging into stark darks. That choice helps the fruit feel firm and illuminated without looking glossy. The peeled lemon at the front lip of the table doubles as a small narrative device. Its spiral peel and exposed pith flaunt the painterly pleasures of whites inside whites, while hinting at themes of ephemerality and taste. You can almost smell the zest.

Knife, Peel, and the Tactile Edge of Reality

Foreground objects do a great deal of work. The knife is placed diagonally, its dark handle embedded in the pale cloth, its blade pointing toward the lemon. It acts as a directional arrow, a scale marker, and a crisp accent that prevents the front plane from becoming too soft. Next to it, the lemon peel spills over the table’s edge—one of those moments where Matisse lets form trespass on the viewer’s space to thicken the sensation of nearness. Together, knife and peel locate us physically with respect to the table while also establishing a subtle narrative: someone has just been here.

Color Strategy: Restraint Charged With Temperature

This painting demonstrates how the young Matisse used restraint to heighten sensitivity. The overall key is low and earthy: olive, bottle green, brown umber, gray-violet, and creamy whites. Within that reduced chord, he adjusts temperature constantly. Whites cool as they turn away from the light; the jug’s spots lean blue-green; the bread warms into sienna; the background hovers in a neutral that shifts warmer near the bread and cooler behind the metal pot. Because he saves higher chroma for small notes—the blush of an apple, the acid of lemon rind—those touches ring clearly without noise. The color discipline anticipates his later, bolder work by proving that color alone, even when limited, can build space and shape feeling.

Edges, Touch, and the Pleasure of Making

The entire scene is built from what painters call “lost-and-found” edges. Where forms press into light, edges soften and dissolve; where Matisse wants a shape to assert itself—knife, lemon, bottle neck—edges sharpen briefly. This oscillation is not decoration. It is how he recreates the experience of looking, where attention focuses and relaxes moment by moment. Brushwork is supple and audible: short crescent strokes model the apples, broad flat strokes lay down the cloth, and brisk, sliding touches articulate the jug’s pattern. The finish is neither slick nor rough; it is alive with the record of the hand.

Organizing Space Without Linear Hyperbole

Unlike academic still lifes that might lock perspective with measured vanishing lines, Matisse constructs space through overlaps, value stacking, and the behavior of color. Objects recede because their contrast diminishes and their temperatures cool, not because the artist laboriously plotted orthogonals. The back wall softly encroaches without seams; the metal pot behind the jug seems to breathe in and out of the scene with slight flickers of value. The result is convincing spatial depth achieved with painterly means rather than architectural drawing.

A Conversation with the Old Masters

Matisse’s apprenticeship included long hours copying in the Louvre, and his admiration for Chardin’s still lifes shows here. The serious attention to everyday objects, the moral weight granted to bread and fruit, and the quiet gravity of the white cloth feel like a salute to that lineage. One can also sense a dialogue with Manet and Cézanne. From Manet comes the frankness of paint and the flattening effect at the picture’s edge; from Cézanne, the notion that objects are constructed by calibrated color planes rather than academic modeling. Yet the voice already sounds like Matisse: decor motifs are stripped to essentials, ornament serves structure, and color is the chief architect.

The Jug with Spots and the Metal Pot: Pattern and Plainness

Two middle-ground vessels reveal different facets of Matisse’s sensibility. The faience jug, white with teal spots, supplies a note of pattern that gently warms the center without sacrificing simplicity. It prefigures the artist’s later love of patterned textiles and wallpaper. Just behind it, the gray metal pot reads in one breath as a solid, utilitarian object and as a soft rectangle of tone—an abstraction serving the balance of the whole. The interplay between patterned and plain, decorative and functional, is a quiet theme murmuring throughout the painting.

Light’s Source and Its Atmosphere

The light seems to arrive from the upper left, catching the bottle shoulders, sliding across the top plane of the bread, and pooling on the cloth. But Matisse resists theatrical highlights. Instead he paints a pervasive, diffused illumination that keeps objects sharing the same air. The background wall, while dark, is not a void. It is a velvety field knit from thin scumbles, allowing the room’s atmosphere to be felt. That unity of light is what lets the lemon peel, the knife, the bottle reflections, and the soft shadow pools talk to one another across the table.

Symbolic Hints Without Allegory

It would be easy to over-read symbols, but still life heritage invites a few quiet readings. The bread, wine bottles, and fruit whisper of sustenance and conviviality. The peeled lemon, traditionally a sign of fleeting pleasures, curls like a question mark at the front edge. The knife introduces a delicate tension, necessary for cutting and serving but also a reminder of sharpness and risk. Matisse transports these long-standing motifs from moralizing allegory to perceptual fact: the objects are first of all themselves and secondarily the bearers of cultural memory.

Cropping, Proportions, and the Modern Frame

Notice how the rightmost bottle is cut slightly by the frame, and how the table’s cloth terminates just shy of the lower edge. Such cropping owes something to photography and Japanese prints, both of which influenced European modernists in the 1890s. The decision creates immediacy. We feel as if the scene continues beyond what we see, and we are encountering a slice of life rather than a staged tableau. The proportions of the arrangement—tall vertical on the right counterbalancing a wider cluster on the left—keep the picture dynamically asymmetrical and, therefore, quietly modern.

Early Matisse and the Road to Fauvism

Placed against the explosive color of Matisse’s later years, this painting might look restrained. But it is essential to understanding how he got there. He is testing how far color, even in muted keys, can organize space and emotion without heavy contour. He is learning that a cloth can be a plane of light, that a bottle’s interior color can be denser than its outline, and that a peel dropped over an edge can make the whole space breathe. Those discoveries remain when the palette intensifies in the early 1900s; only the volume on the color dial changes.

Material Presence and the Sense of Time

The painting carries the time of its making. You can trace where the bread’s contour was corrected, where the lemon’s edge was pushed forward with a more opaque stroke, where the glass reflection was reduced to a single pull of the brush. That accumulation of decisions produces a felt duration, as if the canvas captures an afternoon’s attention. The objects embody patience, and the picture asks for the same in return. To look slowly is to see more: the green inside the tall bottle, the small warm square on the loaf, the whisper of canvas under thin paint in the wall.

The Human Scale of Domestic Beauty

“Still Life with Fruit and Bottles” is at heart a confession that domestic life is worthy of rapt attention. There is no grand event taking place, only a loaf cooling, fruit ready to be cut, and vessels awaiting use. Yet Matisse invests these humble presences with gravity through balance, light, and touch. The result is a picture that ennobles the everyday without sentimentalizing it. In doing so, it lays a cornerstone for the artist’s lifelong project: to create an art of clarity and pleasure that supports life rather than escaping it.

How the Painting Teaches Us to See

Spend a few minutes with the picture and it gently retrains the eye. Whites are never simply white; they lean warm or cool depending on context. Greens are not single notes; they contain olives, bottle-green, and yellow-green tuned for distance or nearness. Glass is not only hard; it also carries the softness of reflections. Shadows are not the absence of light but a society of colors conversing in low voices. The canvas becomes a lens through which daily objects—your own table, your own fruit—may appear newly vivid.

Closing Reflections: The Quiet Courage of Restraint

Matisse’s bravery here is the courage to be quiet. He declines spectacle and chooses patience. He asks color to shoulder the burden of structure, and he trusts the viewer to meet him halfway. The reward is a still life that feels lived-in rather than posed, tender rather than flashy, and rigorous rather than fussy. Beneath its calm surface lies the conviction that painting can make us more attentive to the world and kinder to our own ordinary hours. That conviction will power Matisse’s art for decades, but many of its essentials are already present on this modest table in 1896.