Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

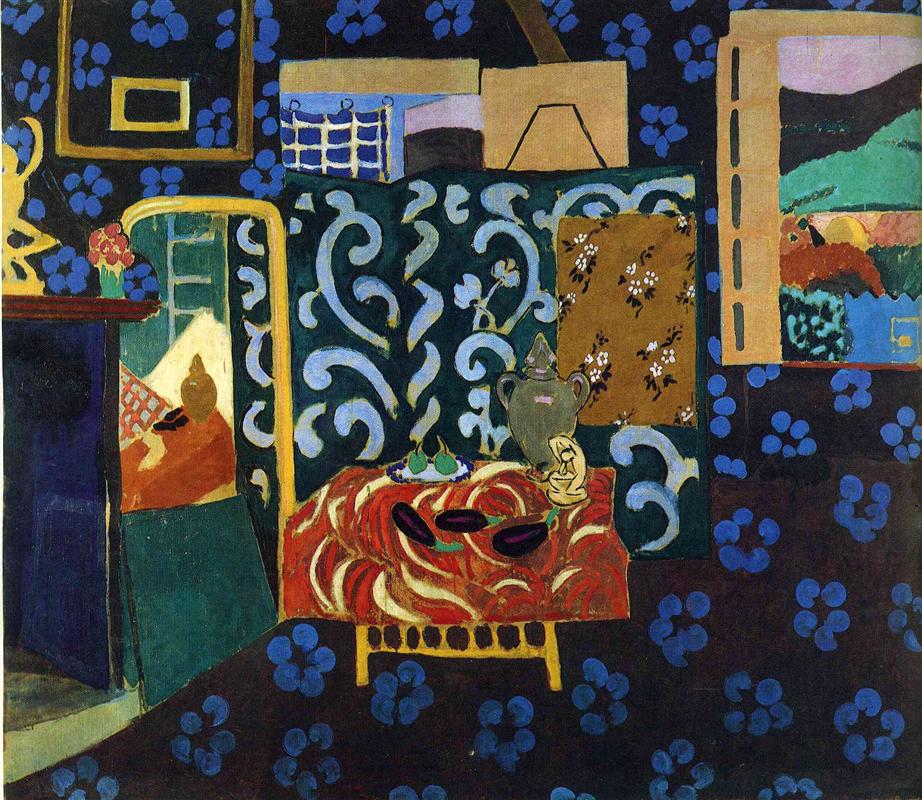

Henri Matisse’s “Still Life with Aubergines” (1911) is a virtuoso performance in which textiles, screens, paintings, and a small cluster of objects collaborate to create a complete interior world. The aubergines in the center are ostensibly the subject, yet the painting is really about how patterns can become architecture and how color alone can assemble a room. A deep, nocturnal ground scattered with bright blue floral marks wraps floor and wall into a single, enveloping climate. Within it, a table draped in fiery red swirls supports aubergines, a lemon, and a pale green ewer; behind the table a teal screen with cool arabesques acts like a painted garden; to the right a rectangle opens onto a stylized landscape; elsewhere, cropped canvases, a small bouquet, and fragments of furniture punctuate the surface. The result is an interior that reads as both a physical place and a map of the painter’s decorative imagination.

The Scene as a Stage of Planes

The canvas is organized as a shallow stage built from large planes that interlock like set pieces. The lowest and largest plane is the dark blue-violet field patterned with electric blue florets, a surface so continuous that floor and wall feel fused. In front of this climate, Matisse installs a low table whose cloth spirals in streaks of red, coral, and ocher; the table’s mustard frame peeks out, an essential band of structure amid the swirl. Immediately behind rises a tall screen painted teal and inscribed with pale arabesques that curl like vines. Smaller rectangles—framed paintings leaned against the screen, a golden-brown textile flecked with tiny blossoms, a window of landscape at the far right—float as inserted images. This collection of planes produces depth without orthodox perspective: each panel announces a zone, overlaps the others, and creates a navigable but compact space.

Color Architecture and Climatic Balance

The painting’s architecture is chromatic more than linear. A near-black blue suffused with violet anchors the entire room; its field, sprinkled with bright blue clusters, suggests a starry textile or a patterned rug. Against that cool mass, Matisse sets three dominant warm families. The first is the flaming red of the tablecloth, whose rhythmic swells make the center pulse. The second is the mustard-gold of frames and table legs, a steadying undertone that holds the composition together like a quiet bass line. The third is the ocher-tan of a pinned fabric patch near the screen, a mellow warmth that mediates between red and blue. Cool colors, too, are subdivided and purposeful: teal and turquoise shape the screen; a higher, icy blue illuminates the arabesque marks and small ladder-like grids; emerald green rounds the ewer and fruit stems. Because the palette is tight and relational, light and depth arise from adjacency rather than from modeled shadows.

Pattern as Structure, Not Decoration

Pattern in this interior behaves as a structural member. The blue florets that speckle the vast field are not filler; they prevent the dark ground from collapsing into void, giving the room a soft lattice that guides the eye’s path. The screen’s arabesques are larger and more legible, functioning like a leafy trellis or a wrought-iron grille that holds the back plane in place. The tablecloth’s pattern is the most kinetic—wide, gestural swirls that turn the tabletop into a whirlpool where the still life gathers. Even the little golden patch at right carries miniature blossoms, stabilizing its rectangular area and preventing it from becoming a simple color block. By deploying patterns at several scales, Matisse distributes attention evenly over the surface and makes “decorative” mean coherent and load-bearing rather than ornamental.

The Aubergines: Weight Within Whirl

Atop the swirling cloth, the aubergines sit like dark boats in a red current. Their elongated ovals echo the blue florets in the ground and the rounded leaves in the small bouquet at left, but their deep plum color and solid modeling give them unusual gravity. They are painted with just enough tonal turning to feel tactile—cool highlights on the curvature, darker bellies against the cloth—yet they never submit to academic description. Their role is double: to concentrate the painting’s warmth at the center and to anchor the table’s movement with palpable mass. The modest lemon and green fruit tighten the color bridge between the ewer and the cloth, while the pale green ewer itself offers a vertical counterweight and a soft, reflective surface that catches bits of neighboring hues.

Screens, Windows, and the Idea of the Interior

One reason the space feels rich without conventional depth is Matisse’s use of nested images. The screen is a picture within the picture: a painted garden set up inside an actual room. The small landscape at the far right is another picture within the picture, a suggestion of outdoors that leans against the dominant interior climate. Framed canvases and fabric samples behave the same way. These inserts act like doors and windows without literal architecture; they provide directional cues and a sense of elsewhere, but they remain flat surfaces, maintaining the primacy of the painted field.

Movement and Rest

Despite abundant pattern, the painting never frays into noise because Matisse organizes movement and rest with care. The red tablecloth, with its broad, sweeping arcs, is the chief engine of movement. The screen’s arabesques provide a slower, echoing motion, their coils more open and measured. The dark ground with bright blue florets establishes the slowest rhythm, a regular beat that quiets the surface. Rest is provided by the solid shapes of vessels, by the gold frames with flat interiors, and by the small landscape’s even bands. This alternation lets the eye roam, pause, and resume like a dance that returns to a refrain.

Drawing with the Brush

Contour is executed directly in paint. A mustard line declares the table’s edge; narrow pale strokes pick out the rims of vessels; the screen’s frame is a quick sweep that thickens and thins with pressure. In places Matisse leaves a halo where one color stops short of another, so a sliver of the underlayer glows at the boundary. Far from careless, these reserves keep the edges alive and announce the surface as a field of decisions. Even small objects—the tiny yellow statuette near the ewer, the delicate vase of flowers at left—are simplified to a few emphatic shapes that hold their own amid the larger planes.

Light by Adjacency

“Still Life with Aubergines” glows without the staging of external light sources. Matisse builds illumination from neighbors. The ewer brightens on the side that faces the tablecloth’s hottest reds; the aubergines glisten where plum meets a light swirl of paint; the screen’s teal deepens where it runs under pale arabesques; the small bouquet appears luminous because its petals sit against a dark shelf. Nowhere does a cast shadow dominate; instead, small differences in value and temperature signal turns of form. This method keeps the interior calm, letting color relations be read instantly across the room and deepening in complexity up close.

A Decorative Logic with Cultural Echoes

The decorative grammar carries echoes of Matisse’s fascination with textiles from North Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Iberian world. The screen’s arabesques recall stylized foliage and ironwork; the tablecloth’s current of swirls suggests woven pattern magnified to painterly scale; the spotted ground reads as a fabric whose repeat binds floor and wall. Rather than quoting a single source, Matisse blends these memories into a modern syntax where pattern organizes space and emotion. The effect is cosmopolitan and intimate at once: an interior made from the world’s textiles, translated into paint.

Dialogues with Matisse’s Other Interiors

This canvas belongs to the family of interiors that includes “Harmony in Red,” “Red Studio,” and the goldfish paintings, yet it has its own temperament. “Harmony in Red” asserts unity through a single commanding hue; “Red Studio” suspends objects as line and islands within a flat field. “Still Life with Aubergines” instead achieves unity through the interweaving of patterned planes. It is less about flooding space with one color than about composing multiple color kingdoms—the dark blue ground, the teal screen, the red tablecloth—into a stable chord, with the aubergines placed like low, resonant notes at the center.

The Psychology of the Room

The mood is nocturne and contemplative. The dark ground suggests evening, while the bright inserts—flowers, fruit, pale rectangles—glow like pockets of lamplight. The room is clearly lived in; pictures lean; a small bouquet freshens the shelf; fabrics are pinned and layered like swatches under consideration. Yet no figure intrudes. The painting proposes a kind of solitude that is concentrated rather than lonely, the atmosphere of a studio tuned for long looking and small adjustments.

Material Presence and Evidence of Process

The surface reveals its making. In the dark ground, one senses multiple passes of blue and violet scumbled into each other, with the brighter florets brushed on top. The screen’s teal is laid broadly, then cut back by pale arabesques; edges show where Matisse adjusted the frame’s curve. The red tablecloth carries thick, confident strokes whose direction betrays the sweep of the arm; the yellow legs of the table are painted last, stitched into place over both cloth and ground. The aubergines themselves are layered—deep plums under cooler glazes—so their skins read as dense without becoming opaque lumps. These traces of process keep the decorative order from feeling mechanical; the room breathes with the history of decisions.

The Table as a Painted Island

The table has an outsized role. It is a pictorial island within the larger sea, a concentrated place where curves, colors, and objects meet. Its rectangular body is barely visible; the cloth’s pattern, rather than carpentry, supplies form. Because the table rests slightly lower than the screen’s base, it establishes a rhythm that steps the eye from foreground to mid-ground to back. The mustard stretcher bars at the front edge are the only clear linear structure in the lower half; they anchor the swaying fabric and acknowledge that beneath every decorative surface lies a frame.

Objects as Characters

Each object performs a character role. The ewer is dignified and upright, a small monument within the pattern. The aubergines are sensuous and reserved, their polished bodies absorbing light rather than throwing it. The lemon and green fruits are quick, bright interjections. The tiny figure near the ewer—reduced to a single silhouette—adds a humorous note, a reminder that life in the studio includes curiosities and small votives. Together these characters animate the tabletop and, by extension, the entire room.

Space Without Anxiety

Matisse’s interiors rarely strive to convince viewers that they could enter and walk around. Instead they invite the eye to inhabit a surface that reads as a place. “Still Life with Aubergines” exemplifies this approach. Overlap, repetition, and color continuity persuade us of spatial relations without demanding the mechanics of vanishing points. The advantage is serenity. The painting holds the viewer in a steady visual climate where attention can move at its own pace and where each return discovers another relation among planes, patterns, and objects.

Lessons for Seeing and Making

The canvas offers practical teachings. Limit the palette to a few families and let complementary contrasts do the heavy lifting. Use patterns at multiple scales to articulate planes and to carry depth without perspective tricks. Draw with the brush so every contour is a living decision. Build light by neighborly relations rather than by theatrical shadow. Place a compact, high-contrast still life where currents of pattern converge, so it can conduct the entire surface. Above all, trust that clarity and abundance are not opposites: a richly patterned room can remain lucid when each element is tuned to the others.

Enduring Freshness

More than a century later, the painting feels startlingly current. Designers recognize the strategy of a dark, patterned envelope relieved by concentrated islands of saturated warm color. Painters still learn from the way Matisse suspends nested images inside a decorative field without sacrificing unity. Viewers find the same reward today as in 1911: the pleasure of watching color think, of seeing a few ordinary things—fruit, a jug, a scrap of textile—organize an entire environment.

Conclusion

“Still Life with Aubergines” stages a conversation between pattern and object, between nocturnal calm and vivid accents, between the flatness of textile and the palpable weight of fruit and clay. The aubergines are the pretext; the true subject is harmony achieved through color architecture and rhythmic planes. Matisse shows how a room can be built from paint alone—how a dark, sparkling climate, a teal garden of arabesques, a red whirl of cloth, and a handful of simple objects can add up to an interior that is serene, intelligent, and inexhaustibly alive.