Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

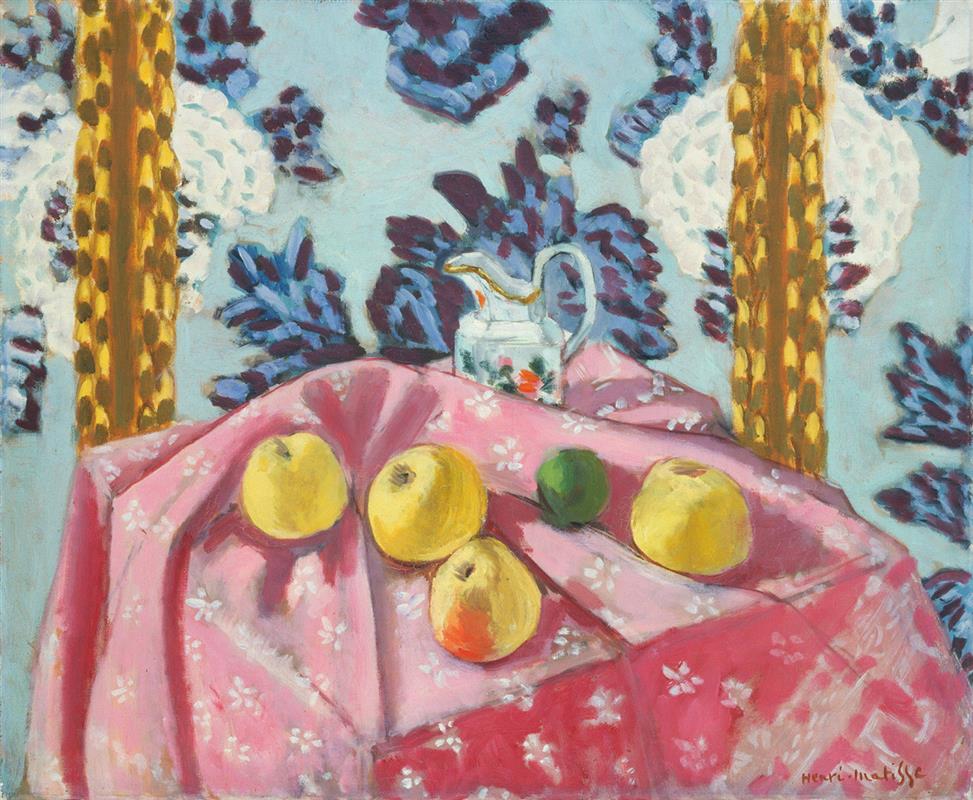

Henri Matisse’s “Still Life with Apples on a Pink Tablecloth” (1924) distills the painter’s Nice-period ideals into a compact, buoyant harmony. A handful of apples and a green citrus rest on a peaked pink textile sprinkled with small white blossoms. Behind them, a light blue wall blooms with dark indigo leaves and white medallions, flanked by two golden vertical bands that read like braided cords or gilded pilasters. At the center of the ridge rises a small glass or porcelain pitcher trimmed with gold. The scene is modest in subject and expansive in sensation: color is climate, pattern is architecture, and each object participates in a wider orchestration where the everyday is tuned until it sings.

Historical Context

By 1924 Matisse had worked in Nice for seven years, trading the explosive contrasts of Fauvism for a modern classicism of ambient light, compressed space, and decorative order. Interiors became laboratories where textiles, flowers, fruit, and small vessels coexisted on equal terms with the human figure. Still life, in particular, was his testing ground for relations: how warm and cool balance, how patterns regulate tempo, how a single note of color can steady a room. “Still Life with Apples on a Pink Tablecloth” belongs squarely in this program. Its vocabulary—tilted tabletops, ornamental backdrops pushed forward, a limited family of hues carefully tuned—shows the painter at ease, yet precise, about what painting can do without narrative.

Composition and Structure

The composition is pyramidal, with the pink cloth pulled up into a central ridge that peaks just before the pitcher. This uplifted fold acts like a small stage, presenting the fruit at a readable angle and preventing them from sliding into deep space. The objects align along a gentle arc—yellow apple, yellow apple, green citrus, yellow apple, and a mottled apple nestled near the cloth’s near edge—each spaced so that the eye moves in a measured rhythm from left to right and back again. The pitcher stands slightly behind the apex, its transparent body and gilt lip catching light and repeating the painting’s essential curves.

Framing this arrangement are two vertical golden bands that stabilize the lateral edges and pace the background like architectural pilasters. Between them, a large field of pale blue is overprinted with dark, leafy motifs and white floral reserves, turning the wall into a tapestry that answers the tablecloth’s smaller blossoms. The whole design reads as a dialogue between big and small patterns, vertical frame and triangular mound, circular fruit and angular folds.

Pattern as Architecture

Matisse uses pattern not as embellishment but as structure. The pink cloth is sprinkled with tiny white blossoms that create a consistent, mid-tempo pulse across the base of the picture. These miniatures keep the plane lively while allowing the form of the folds to remain legible. The wall pattern behind enlarges the motif dramatically: deep indigo leaves fan across the blue field, punctuated by larger white medallions whose scalloped edges echo the little flowers in a slower meter. This scale shift—micro blossoms below, macro blooms above—locks the composition together, like two staves of music playing the same theme in different registers.

The golden bands operate as metronomes. Their dotted inner textures, painted with warm ochre dabs, provide a secondary beat that anchors the sides and prevents the broad wall from drifting away. With these devices Matisse builds a stage where depth is suggested by overlap and temperature rather than by vanishing points. We look from pattern to object and back again, never leaving the surface.

Color Climate

Color is the painting’s atmosphere and logic. The dominant chord—pink, blue, and gold—produces a climate that is simultaneously cool and sunwarmed. The pink tablecloth supplies tenderness and radiance; its whites and pale coral lights keep it from cloying. The sky-blue wall cools the space, making the fruit’s yellows feel juicy and the gold bands glow. The indigo leaves adjust the key downward so the high notes do not squeal; they provide necessary gravity. Between these fields sits the fruit: three sunlit yellow apples, a green citrus that acts as a cool pivot, and a mottled yellow-pink apple whose blush mirrors the cloth. The small pitcher carries bright pinpoints of red and green in a painted flower—miniature echoes of the larger palette—and a gilt rim that repeats the gold of the flanking bands.

Matisse avoids dead black. Even the darkest indigo leaves are chromatic, and the shadows that pool beneath apples are tinted violets and cool reds. This keeps the surface breathing and the colors in conversation rather than in conflict.

Light Without Theatrics

The illumination is ambient—one of the Nice period’s signatures. There is no harsh spotlight carving hard shadows; instead light seems to soak the room evenly. On the cloth, highlights gather along the ridge and drop off into cooler valleys; on the apples, hemispherical glows bend softly around their volume; on the pitcher, a milky sheen traces the curve of glass and catches on the gilt lip. Because light is general, color carries expression. The result is serenity: we experience not a dramatic moment but a sustained climate of attention.

Drawing and the Economy of Contour

Matisse draws with planes and elastic lines, spending detail only where it clarifies structure. The apples are bounded by supple contours that thicken and thin with pressure, a visible record of the brush’s speed. Their stems are brief, calligraphic flicks—enough to specify orientation without fuss. The pitcher’s outline is a single, confident thread looping spout and handle, then reinforced where transparency meets background. The folds of the cloth are mapped by broad, simplified planes, not by fussy creases. Everywhere, contour breathes: tighter where objects meet the backdrop, looser along internal turns. This economy keeps the painting fresh and lets color do the descriptive work.

Space by Layers, Not Vanishing Points

Depth arises from stacking and temperature rather than linear perspective. Foreground: the near lip of the cloth’s edge, tipped just enough to meet the viewer. Middle: the ridge with fruit. Back middle: the pitcher standing a step behind. Background: the patterned wall pressed forward by the golden bands. Each layer is clearly stated, and the intervals between them are short; this shallowness brings the viewer close, as if one could reach out and cup an apple. It also preserves modern flatness, reminding us we are looking at orchestrated color shapes rather than a window onto illusionistic depth.

Rhythm and Tempo

The painting’s rhythm is built from repeating shapes and measured intervals. Round fruit repeat across the ridge; small white blossoms repeat across the pink; large indigo leaves repeat across the blue; the two gold pilasters repeat each other and bracket the scene. Between these steady beats, Matisse introduces syncopations: the single green citrus breaks the yellow sequence; the mottled apple disrupts uniformity with a warm blush; the pitcher, light yet vertical, interrupts the horizontal procession of apples and introduces a pause before our eyes move into the background. These cadences guide how long we linger on each element, giving the still life a musical shape.

The Pink Tablecloth as Protagonist

Though the title calls attention to the apples, the cloth is a true protagonist. Matisse engineers its folds into a miniature landscape—ridge, slope, and basin—on which light and color can play. The pink itself is subtly varied: cool rose in shadow, salmon on the up-facing planes, and bright strawberry where it catches the most light. The small white florets, dabbed quickly with the brush’s tip, bind the field without freezing it. The cloth holds everything: it gives the apples weight, the pitcher place, and the viewer a tactile sense of presence. In Nice-period still lifes, textiles are not backdrops; they are the architecture that makes the picture possible.

The Apples and the Sensation of Fruit

Matisse resists literal description and aims instead at the sensation of fruit. Each apple is a compact, well-tuned chord: a warm yellow body, a cooler half-shadow brushed in lavender or green, a firm highlight that tells us about the skin’s tautness. The green citrus acts as a cool pivot, preventing the yellow sequence from becoming monotonous and linking fruit to the blue field behind. The slightly bruised or blushed apple near the lower center is a savvy stroke; its orange-pink echo of the cloth locks fruit and textile into the same atmosphere. The result is not a plateful rendered from observation alone but a set of volumes perfectly tuned to the picture’s climate.

The Pitcher as Counter-Form

The small pitcher is a structural hinge. Its transparency softens the vertical, preventing it from reading as a hard barrier. The gilt rim and painted blossom supply tight, high-frequency accents that keep the center alert. It also mediates between the human touch of the tablecloth and the abstracting pull of the wall pattern. In Matisse, such small vessels often play this mediating role; they are like glissandos linking chords.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The painting remains tactile. On the wall, indigo leaves are laid in with loaded strokes whose edges feather where the brush lifts; white medallions are scumbled, letting the blue peep through like woven cloth; the gold bands show short, repeating dabs that catch light and imply depth without literal relief. On the cloth, long pulls of semi-opaque paint give the folds weight; over them, tiny blossoms are tapped in, some squashed and smeared to keep them alive. On the apples the paint turns, following form, with highlights added in a single, confident touch. These varied pressures and speeds prevent the surface from becoming a mere design; it remains a record of making.

Dialogues with Other Nice-Period Works

Compared with Matisse’s rich odalisque interiors of 1923, this still life is quieter and more abstract in aim. It dispenses with the figure to focus on the language that underpins those figure pictures: pattern as architecture, color as mood, shallow space as stage. Against the darker, more saturated “Piano Player and Still Life” (1924), it feels airy; the light blue and pink create a springlike key in which fruit, not music, sets the tempo. And compared with the 1912–13 “Goldfish” canvases, which use water as a color-transforming lens, this painting keeps transformation on the surface—through textile and wall rather than glass—showing how the same harmonies can be fashioned from cloth and pigment alone.

Meaning Through Design

What does “Still Life with Apples on a Pink Tablecloth” ultimately propose? That beauty need not rely on rarity or narrative. A few apples, a modest pitcher, a patterned cloth, and a receptive wall can, when tuned, produce a climate of clarity. The painting models an ethic of arrangement: set things in sympathetic relation, balance warm and cool, let pattern pace the eye, and calm will gather. In a world of distraction, this is not trivial. Matisse engineers a space where attention can rest and renew itself.

How to Look, Slowly

Enter from the left and circle the first yellow apple, noting the soft violet along its lower arc. Step to the second and feel the slight change in spacing, a different interval in the melody. Pause at the green citrus and let its coolness rinse the surrounding pink. Cross to the third yellow apple and then to the blushed fruit near the edge, whose orange echoes the cloth. Climb the central ridge to the pitcher, trace the gilt lip, and follow the handle’s curve into the blue field. Let your gaze expand to the indigo leaves and white medallions, then return down the golden band and back to the cloth’s small blossoms. Repeat the circuit; with each pass, the picture’s grammar grows clearer.

Conclusion

“Still Life with Apples on a Pink Tablecloth” is a lucid statement of Matisse’s late-Nice conviction that color and pattern can shoulder the expressive burden once reserved for story and illusion. A pink textile staged like a small mountain, a handful of fruit tuned to its atmosphere, a tiny pitcher acting as hinge, and a decorative wall pressed forward as architecture—these elements cohere into a poised, musical whole. The painting does not shout; it concentrates. It offers a usable wisdom for both painters and viewers: when relations are exact, the simplest things radiate.