Image source: wikiart.org

Overview and Why This 1904 Canvas Matters

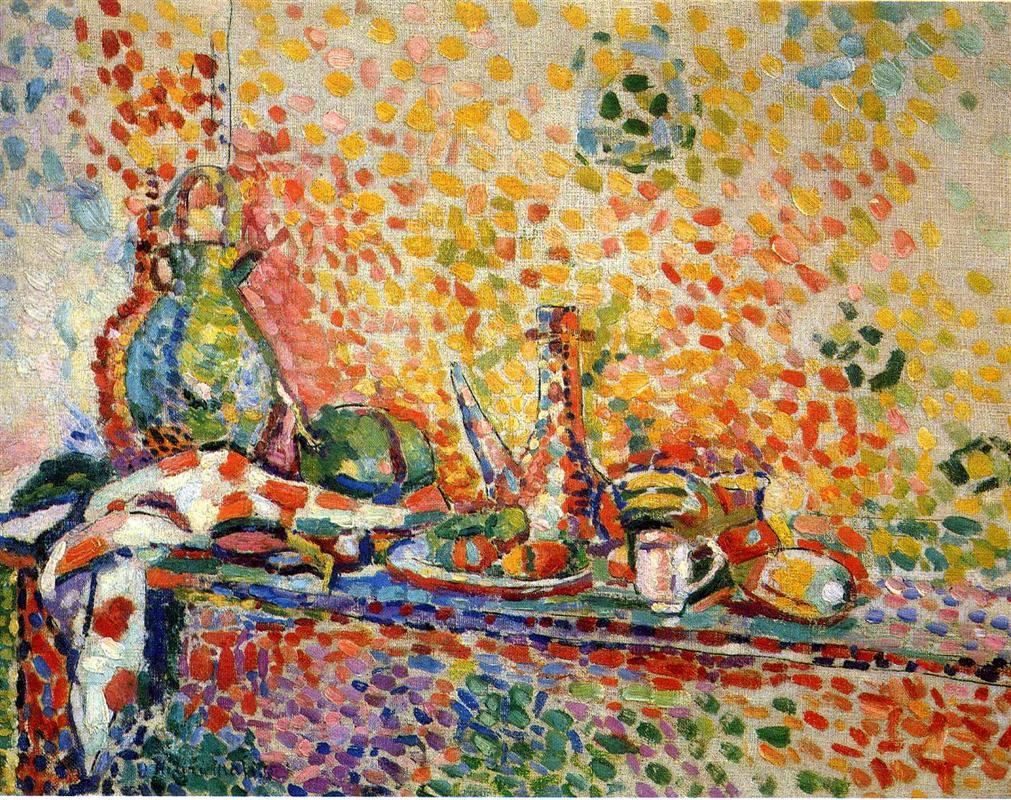

“Still Life With A Purro (II)” is a crucial hinge in Henri Matisse’s evolution from the tempered structurality of Cézanne to the blazing chromatic freedom of Fauvism. Painted in 1904, the same period as his seminal Mediterranean experiments, the work translates a tabletop arrangement of pots, bottles, fruit, a white cup and a checked cloth into a vibrating field of divided color. The title’s “Purro” points to the rustic earthenware jug that anchors the ensemble, but the picture’s true subject is optical energy. By reimagining domestic objects through short, tessellated strokes and high-key complements, Matisse tests Neo-Impressionist procedures while pushing them toward the emotional heat that would define his Fauve breakthrough in 1905.

Historical Context and Matisse’s Search for a New Language

At the turn of the century Matisse studied Cézanne’s constructive brushwork, adopted Gauguin’s taste for non-naturalistic color, and looked closely at Seurat and Signac’s Divisionism. In 1904 he worked along the Côte d’Azur where Mediterranean light sharpened his chromatic sensitivity. Out of this climate emerged “Luxe, calme et volupté,” a pointillist-inflected landscape that nonetheless felt warmer and more improvisatory than Seurat’s analytic order. “Still Life With A Purro (II)” belongs to the same exploratory season. It is a studio laboratory piece that lets him test whether broken color and small touches could carry not only sunlight and air, but also the heft of pottery, the gleam of glass, and the tactile pleasure of a tablecloth. The canvas therefore records a transitional grammar: the dots and dashes of Divisionism are present, but they are larger, more expressive, and keyed to sensation rather than optical theory alone.

Composition: A Tabletop Turned Into a Stage of Color

Matisse aligns the still life on a long table set slightly below eye level, tilting the plane so that objects parade from left to right. The stout green purro rises at the far left like a rounded pillar, its handle forming an arch that introduces the painting’s motif of curves. A melon nestles beside it, and at mid-canvas a tall bottle and slender carafe punch vertical accents. To the right, a white cup, a red-orange fruit and a curved pitcher and pear complete the procession. This horizontal rhythm is countered by the diagonal of the tabletop edge, which slides from lower left toward upper right, and by the slanted fall of the checked cloth. The composition is classic still-life architecture, but Matisse makes the grid breathe by distributing weight with color rather than line. Darker greens and blues stabilize the left; warm oranges and yellows flare toward the center and right, encouraging the eye to shuttle across the surface in loops rather than a single sweep.

The Divided Touch: From Theory to Feeling

The most striking feature is the stippled skin that covers nearly everything. Matisse lays down short ovals and commas of pigment—crimsons, canary yellows, sap greens, ultramarines—that overlap without fully mixing. This is Divisionism in practice: discrete notes that blend in the eye at a distance. But he departs from Seurat in three decisive ways. First, the marks vary in size and pressure; they are not a uniform scientific tessellation but a living texture that swells and thins with the forms underneath. Second, the color intervals are broader, leaping across the wheel from cools to warms in quick succession, with little of Seurat’s measured transitions. Third, the marks describe not just light but material. Along the purro’s belly the dabs elongate into arcs that imply curvature. On the bottle they cluster into ladders of highlights and shade, and in the cloth they collect along folds to mimic weave and drape. Technique is subordinated to touch; the dots are not a system but a feeling.

Light, Atmosphere, and the Mediterranean Memory

The background is a mist of lemon, peach, and pale blue dashes that suggests a wall being showered with sunlight. Rather than cast hard directional shadows, Matisse fills the space with ambient radiance. White grounds flicker through the mesh of strokes, letting the surface breathe. Mediterranean light enters the room as colorized air. This choice matters because it collapses the hierarchy between foreground objects and their setting. Fruit, bottle, cup, and wall all participate in the same luminous climate, turning the still life into an ecosystem rather than a lineup of isolated things.

Color Harmonies and Chromatic Tensions

A limited but intense palette drives the painting’s mood. Green and red act as the primary complementary pair, pulsing around the purro, the melon, and the tomatoes or oranges at center. Yellow and violet supply a secondary tremor that animates the background and glints off metal and glass. Matisse deploys neutrals selectively, rarely resorting to brown or black, preferring instead deep blues and greens to carry shadow, and milk-white strokes to signal specular light. These decisions prevent the painting from congealing. Even the darkest passages retain chromatic life, and the brightest zones are modulated enough to avoid glare. The effect is musical, with chords established by complementary pairs and resolved by small mediating notes. Matisse later spoke of seeking “balance, purity, and serenity”; here that balance is achieved not by muting color but by letting opposites stabilize each other.

The Purro as Anchor and Sign

The rustic jug deserves its spotlight in the title. Its mass and humble profile connect the painting to daily use and to the South’s domestic pottery traditions. Set against the scintillating wall, the purro’s larger patches of green and blue steady the eye. It also stages a dialogue of surfaces: its matte ceramic absorbs light, the bottle beside it flashes with highlights, and the cup at right reflects light softly. Together they form a trio of receptacles—earth, glass, porcelain—that demonstrate how different substances negotiate illumination. The symbolism is quiet but potent. Vessels contain; painting, too, is a vessel for light and feeling. Matisse’s still life therefore becomes an allegory of containment and release, with color as the liquid that overflows its boundaries.

Space, Depth, and the Productive Ambiguity of the Picture Plane

The tabletop promises recession, but the stippled wall insists on flatness. Matisse maintains a fertile uncertainty between these readings. The cloth’s downward diagonal and the diminishing size of items toward the right suggest depth, yet the even distribution of marks across figure and ground pulls everything forward. Bottles and fruits are outlined not by contour but by the pressure difference between neighboring strokes. This makes edges feel permeable, as if the objects were breathing into the space around them. Such ambiguity is not a flaw; it is one of Matisse’s enduring strategies for reconciling modern flatness with the pleasure of spatial illusion.

The Checked Cloth: Kinetic Color and Human Trace

Draped over the table’s edge, the white-and-red cloth performs several duties at once. It supplies the sharpest value contrast in the picture, punctuating the composition with bright notes and anchoring the left side. It injects a sense of movement, its flickering squares tilting and folding like a flag in slow wind. And it introduces the human trace. The cloth implies handling, cooking, serving—the intimate chores that tether painting to life. In Matisse’s universe textiles are never mere props; they are color machines that also carry memory.

From “Still Life With a Purro” to “Still Life With A Purro (II)”

Comparing this canvas with the earlier, more Cézannian “Still Life With a Purro,” one sees the shift from constructed planes to optical quiver. The first painting models volume with broad, directional strokes and keeps the background quieter. The second detonates the wall into an atmospheric mosaic and lets pointillist energy seep into the objects themselves. Form is still legible, but it is defined by color contrasts rather than by weighty contour. This evolution reveals Matisse’s growing conviction that color could shoulder the entire burden of representation and emotion.

Dialogues with Seurat, Signac, Gauguin, and Van Gogh

Matisse’s dotted skin acknowledges Seurat’s legacy, but the comparison clarifies his originality. He rejects Seurat’s strict optical calculus in favor of instinctive, hand-scaled marks that change size and cadence whenever the form or feeling demands. Signac’s coastal canvases likely encouraged Matisse’s sun-saturated palette, while Gauguin’s example green-lights the freedom to assign nonlocal color. Van Gogh’s impulsive stroke hovers behind the painting’s gusts of energy, particularly in the denser eddies near the purro and the bottle. The work synthesizes these sources without diluting any of them, pointing toward the independent chromaticism that would scandalize and delight viewers at the 1905 Salon d’Automne.

Materiality and the Pleasure of Paint

“Still Life With A Purro (II)” is a feast for anyone who loves paint as substance. You can track the drag of the brush as it drops a small oval of cadmium yellow, then—without cleaning—grabs a lick of vermilion, resulting in strokes that carry their own internal mixtures. The surface has the granular liveliness of stucco in sun. Thick clusters near the objects give a sense of corporeal presence; thinner scatters in the background preserve luminosity. If the earlier still life emphasizes the solidity of things, this one celebrates the liquidity of vision, where forms appear to melt into the atmosphere that surrounds them.

Tempo, Rhythm, and Visual Music

The painting reads like a score. Large, slow notes gather at the purro and the melon; quicker arpeggios dance around the bottle’s neck; syncopations skip across the checked cloth; trills and tremolos ripple through the wall where yellow, orange, and blue collide. The tabletop edge is the staff line that holds the music together. By appealing to rhythm rather than outline, Matisse invites a form of looking that unfolds in time. The viewer scans, returns, compares, and re-hearses harmonies, discovering new chords as the eye moves.

Process, Revisions, and the Trace of Decision

Close looking suggests that Matisse adjusted the positions of objects as the painting progressed. Edges are negotiated, not drawn; fields of dots gather to strengthen a contour or disperse to loosen it. The bottle’s bright highlight appears to have been reinforced late in the process, sharpening its vertical authority. The wall’s densest swarms hover behind focal objects, a subtle tactic that pulls figure from ground without resorting to outline. These traces of decision keep the work fresh. It is not a system executed; it is a mind thinking in color.

Meaning Beyond the Table: Modernity at Home

Matisse often argued that modern painting did not require novel subject matter so much as a novel way of seeing. A still life, stripped of drama and narrative, lays bare the painter’s choices. In “Still Life With A Purro (II)” those choices are radical. The domestic is transformed into the incandescent. A kitchen jug and a cup become vehicles for chromatic speculation. A wall becomes weather. In doing so the painting proposes a modern ethic of attention: to grant ordinary objects the dignity of intense regard and to accept color not as decoration but as the primary language of feeling.

Legacy and Foreshadowing of Fauvism

This canvas foreshadows the scandal and triumph of the Fauves. Its high-key palette, liberated touch, and compressed space point directly to the works Matisse would show with Derain and Vlaminck in 1905. Yet it preserves a contemplative balance that remains distinctively his. The painting is exhilarating without being frantic, experimental without being mannered. It shows the artist discovering how to make color carry structure, atmosphere, and emotion all at once, a discovery that would reverberate through his interiors, odalisques, and late cut-outs.

How to Look at the Painting Today

To meet this work on its own terms, let your eye idle across the surface rather than jumping to outlines. Notice how red heats up beside green, how yellow cools where blue drifts near, how a white stroke can act as both light and breath. Step back to experience the optical blend that makes forms cohere; then move in close until the world breaks into separate chips of paint. This oscillation between distance and proximity is the painting’s engine. It performs the miracle Matisse pursued throughout his career: harmony achieved not by suppression of difference but by the happy coexistence of strong, independent notes.

Conclusion: A Laboratory of Light and a Pledge to Color

“Still Life With A Purro (II)” is more than a variation on a tabletop theme; it is a pledge—to color, to sensation, to the promise that painting can transmute the ordinary into radiance. By filtering the language of Divisionism through his own sensuous intelligence, Matisse discovers a path beyond theory toward a more generous modernism, where the pulse of life and the logic of composition are one and the same. The rustic jug, the reflective bottle, the humble cup, the glowing fruit, and the vivacious cloth become a chorus through which the artist announces, quietly but unmistakably, that the future of his art will be written in color.