Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

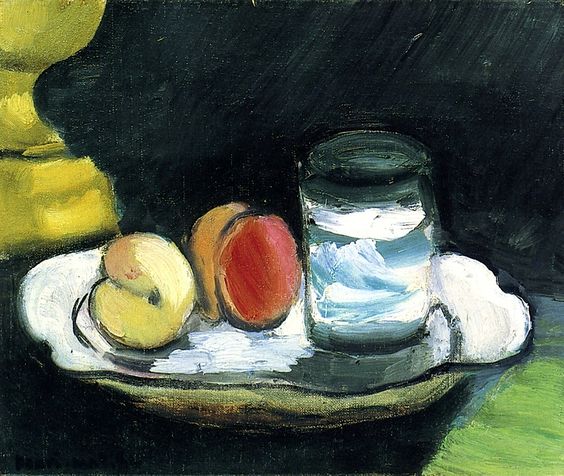

Henri Matisse’s “Still Life, Peaches and Glass” (1916) is a small, concentrated lesson in how a few ordinary things can become a complete world when they are tuned by color, contour, and light. A white plate holds two peaches and a halved fruit whose scarlet flesh faces us like a signal; a short glass filled with water sits beside them, its elliptical rim and bright internal reflections cutting through the surrounding dark. The background is nearly black with green and yellow incursions, a stage set by brushwork rather than detailed description. Out of this restricted cast, Matisse builds a drama of intervals—round against square, gloss against matte, white against night—so finely calibrated that the eye never tires of circling the scene.

Historical Moment

The picture belongs to Matisse’s wartime period (1914–1917), when he pared his language after a decade of chromatic exuberance. In these years windows became gridded abstractions, portraits were distilled to masklike planes, and still lifes were rebuilt from a handful of decisive shapes. The austerity was not a retreat but a search for structure: how little is needed for the image to breathe? “Still Life, Peaches and Glass” answers by choosing just four actors—plate, fruit, glass, ground—and letting relations do the expressive work. It bears the discipline of 1914–1916 yet keeps the sensual promise of Matisse’s earlier colorism: even in sobriety, the scarlet peach and the milky glass shine.

First Impressions

At a glance the painting reads as a bright island afloat on darkness. The scalloped white plate anchors the center; a wedge of acidic green intrudes from the lower right and a lemony pillar flares at the left margin, pushing the plate forward. On the plate the peaches settle in a gentle arc, from yellow-green sphere to the halved red fruit to a deeper ochre form that bridges glass and fruit. The tumbler of water stands absolutely vertical, its transparent cylinder catching and splitting the light from the plate. Everything is simplified to maximum legibility: no tablecloth threads, no background furniture, only the necessary signs of volume and light.

Composition and Geometry

Matisse composes by countering curves with axes. The glass is a stack of ellipses—rim, waterline, foot—held in precise vertical alignment. The plate is another, larger ellipse tilted just enough to show its inner lip and catching a flare of white on the far edge. The peaches are spherical interruptions along the plate’s long axis, their sizes stepping down from left to right to guide the gaze toward the luminous glass. The three fruits form a triangle that triangulates with the cylindrical glass, a stable geometry that allows the brush to remain lively without loss of order. Negative space matters: the dark bay to the right of the glass and the black behind the halved peach carve the light forms into prominence.

Color Architecture

The palette is restricted and strategic. Deep black-green covers most of the field, absorbing light and intensifying the plate’s whites. The peaches are mixtures of ochre, saffron, and soft rose, with a single blaze of cadmium red in the cut fruit. The plate’s whites are not a single note but a chord: dead white in the brightest glare, bluish grays in shadow, milky impasto where the brush ridges hold light. The glass, nominally colorless, becomes a vessel for color: its inner reflections carry plate whites, sky blues, and faint greens from the surroundings. The yellow pillar at left and the green band at right are not descriptive anchors so much as temperature levers that keep the picture from chilling; they warm the climate just enough to make the central whites and reds gleam.

Light and Value

The painting’s light is manufactured rather than copied. There is no mapped-out spotlight, no diagrammatic cast shadow. Instead Matisse assigns values to planes so that things feel illuminated. Notice how the plate’s far rim carries the highest accent, a narrow ribbon of thick white that instantly establishes the object’s gloss. The transparent glass is lit by value contrast, not by painstaking highlights: a bright internal band sits against a darker strip of water, a pale rim floats over a black ground. The peaches are modeled with two or three steps at most—warm light, cool half-tone, quick shadow—enough to turn the form without fuss. This economy produces an overall brightness that feels natural even as it is entirely constructed.

Drawing and Edge

Contour is purposeful and varied. The plate’s outer edge is a fat, broken line that alternately dissolves and insists, imitating the way porcelain blurs in glare and bites in shadow. The glass’s rim is sharply stated and perfectly elliptical, but the lower edge softens into the plate, a truthful acknowledgment that transparency erases boundaries. The peaches are defined by soft, elastic edges; only where fruit meets plate does the line harden to stop the forms from sliding. Throughout, edges are not simply borders; they are instruments that set the painting’s rhythm.

Brushwork and Surface

The surface is open and legible. In the ground, long diagonal sweeps of dark paint leave a subtle nap—bristles track the light, keeping the darkness active. The plate is built with short, thick strokes laid around the ellipse like pieces of shell; small gaps let undercolor breathe, preventing chalky monotony. The peaches show a round, rubbing touch that rolls color around the form; sometimes Matisse drags a drier brush so that the canvas weave shows through, a texture that suggests velvety skin without descriptive fuss. The glass receives the smoothest handling of all, with horizontal flicks that suggest the water’s meniscus and the rim’s slickness. You can read the order of operations: ground first, plate next, fruit placed, glass finished, then a final pass of highlights to weld them.

The Role of White

White is the protagonist. It is the plate’s body, the glass’s glint, the light that calibrates every other hue. Matisse uses multiple whites—zinc-like cools, warmer lead-like notes—stacked to avoid deadness. The highest whites sit thick, catching ambient light as actual relief; lesser whites are thin, nearly transparent. Because white appears in discrete, tuned patches, the eye hops from accent to accent, creating a visual tempo that animates the stillness of the subject.

Peaches as Emblems

Matisse reduces the fruits to a few telling signs: a pale hemisphere with a greenish cast for one whole peach; a deep orange-ochre for the middle fruit whose weight counters the glass; and the halved peach, split to reveal scarlet flesh bordered by a thin ring of cream. He resists the temptation to detail fuzz, stem, or pit. The fruits’ job is not botanical; it is musical. They introduce warm color, provide rounded forms, and carry the association of taste and summer into a picture of wintery restraint. Their sizes, spacing, and temperature keep the plate from becoming a mere platform for the glass.

The Glass: Transparency and Reflection

The glass is a marvel of reduction. A few curved stripes and patches communicate transparency, reflection, and refraction. The white sliver that crosses the water’s surface reads as a reflection of the plate; the pale rectangle within suggests a window or light source outside the frame; a dark bar near the rim arrests the eye and prevents the cylinder from evaporating. Importantly, the glass is not an outline filled with tone; it is an object built from edges and interior events. By refusing to over-describe, Matisse lets the viewer’s experience of glass do half the work, making the illusion feel both convincing and modern.

Space and Tabletop

Depth is shallow and intentional. The plate sits on a ledge implied by the green right-hand plane; the black field behind eats depth rather than expressing it. This compression pulls the still life toward the picture plane, preserving the decorative unity that mattered to Matisse. Yet the space is not flat. Overlaps—glass over plate, peach against rim—and the narrow shadow under the plate’s lip provide just enough perspective for the mind to place things. The result is a believable tabletop that functions primarily as a stage for color and shape.

Cropping and Scale

Matisse crops boldly. The yellow form at left is only partly visible; the green strip at right is cut by the frame; the plate itself pushes dangerously close to the lower edge. These decisions give the small picture a sense of immediacy—objects have been seized in a glance, not arranged for a catalog. Scale is human and domestic: the glass is short, the fruits close at hand, the plate modest. That modesty is key to the painting’s authority; it argues that large truths about painting can be discovered in small, familiar things.

Influence and Dialogues

“Still Life, Peaches and Glass” converses with the lineage of still life without quoting it. You can hear the sobriety of Chardin in the weight of the plate and the silence of the room; the constructive sense of Cézanne in the geometry of ellipses and spheres; and Matisse’s own earlier colorism in the sudden red of the halved peach. Yet the picture is unmistakably his: the black field, the compressed depth, the reticent but decisive highlights, and the decorative tuning of whites and warms mark it as a wartime Matisse through and through.

Symbolic Hints Without Allegory

The French “nature morte”—dead nature—always carried a whisper of mortality. Here it is heard in the cut fruit’s exposed red and in the glass of water, that most elemental of sustenance. But Matisse refuses allegory and moralizing. If there is a meditation here, it is about attention: how looking can refresh ordinary things until they seem newly made. The peaches are not vanitas emblems; they are concentrated moments of taste and color captured before they pass.

Evidence of Process and Revision

Look closely and you’ll find the painter’s edits. A soft halo along the plate’s right edge suggests the rim was moved outward late in the work. The glass’s foot carries a ghost of an earlier position. Around the halved peach a darker ring peeks under the final red, deepening the fruit and keeping it from floating. These traces matter because they reveal how final clarity emerges from adjustment; the painting’s ease is achieved, not automatic.

How to Look

Let the white plate anchor your eye; then move to the red half-peach and feel how it pulls you toward the glass. Track the inner whites of the tumbler and watch them reorganize themselves as reflections rather than objects. Step back so the dark field presses the light island forward; step close until you see the ridges of white catching real light. Try squinting: the painting holds as a simple map of shapes and values, proof that its structure is sound. Then open your eyes wide to enjoy the variety of touch that animates each area.

Lessons for Painters and Designers

The canvas offers durable lessons. Restrict the palette and you gain control over temperature; let whites be many, not one; build glass by staging contrasts inside it; use cropping to energize small formats; and trust negative space to do half the expressive work. Most of all, set relations rather than descriptions: when the ellipse of the glass is tuned to the ellipse of the plate and the red of the peach is calibrated against the surrounding greens and blacks, the painting breathes on its own.

Conclusion

“Still Life, Peaches and Glass” exemplifies Matisse’s wartime ideal: a spare, luminous order where a handful of tuned elements carry the full weight of sensation. The bright plate, the red fruit, and the clear water are not merely described; they are orchestrated so that each clarifies the others. The picture feels calm and exact, but it is not dry. It remembers taste, coolness, summer and light, even as it insists on surface and structure. Over a century later, the canvas still feels freshly poured: proof that when relations are precise and touch is alive, a few peaches and a glass can hold a world.