Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy, Summer 1889

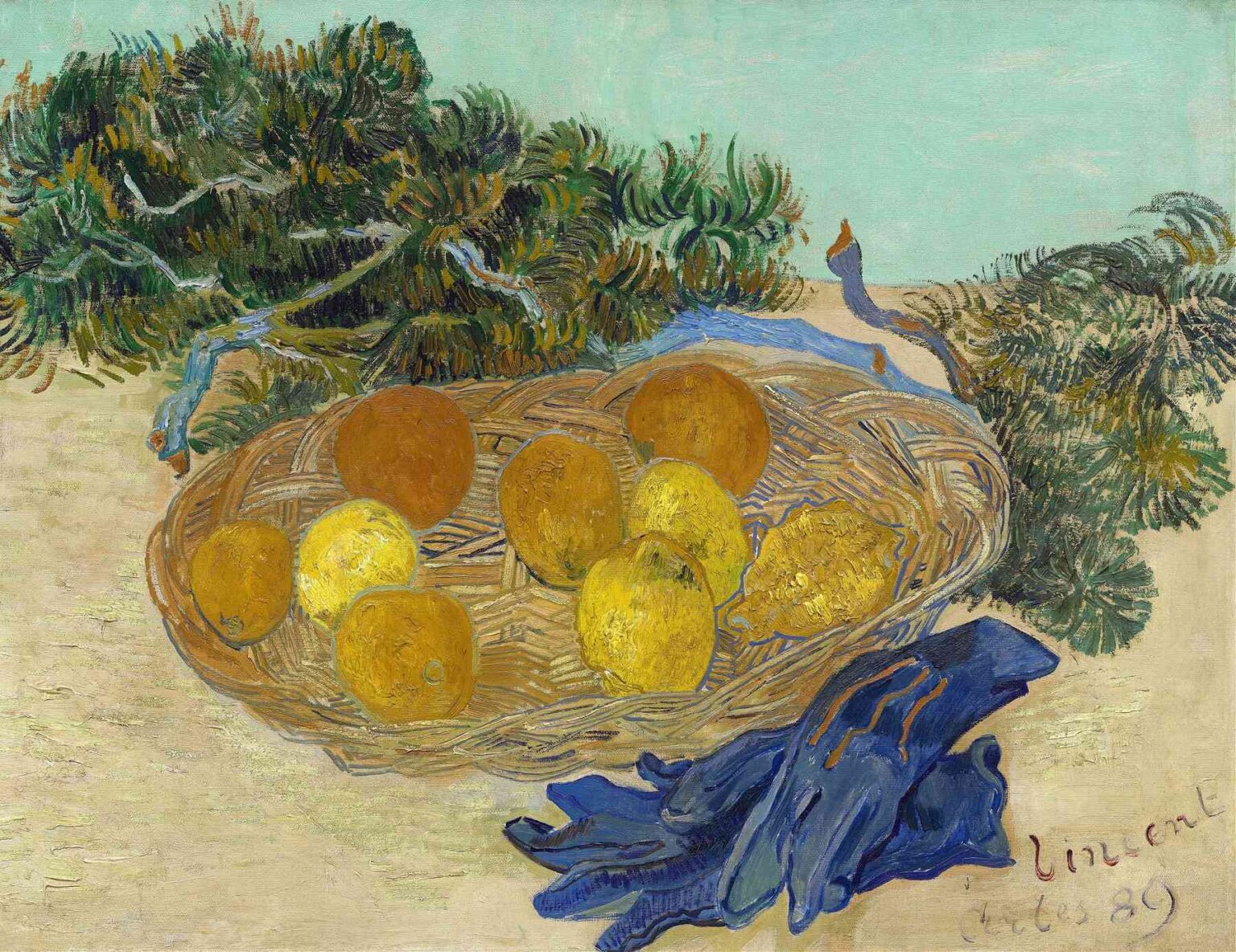

In May 1889, Vincent van Gogh voluntarily admitted himself to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, seeking relief from his mental health struggles. Despite—or perhaps because of—his confinement, Van Gogh entered one of the most prolific periods of his career, painting more than 150 canvases in just over a year. Among these were landscapes of cypress groves and wheat fields, as well as a surprising number of still lifes and floral studies. Painted in late June 1889, “Still Life of Oranges and Lemons with Blue Gloves” reflects Van Gogh’s evolving preoccupation with everyday objects as conduits for emotional expression. Here, the artist turns his attention to a tabletop arrangement that marries vibrant fruit, a sumptuous basket, sprigs of green foliage, and an unexpected pair of blue gloves—each element rendered with characteristic impasto and rhythmic brushwork.

Subject Matter and Composition: A Harmonious Assembly

At first glance, the painting appears deceptively simple: a shallow basket holds seven citrus fruits—three lemons and four oranges—nestled among leafy branches. The basket sits on a pale, neutral tabletop, while a pair of blue gloves rests casually in the foreground, partially draped over the table’s edge. Behind the basket, a wall of green foliage suggests an outdoor garden or veranda, suffusing the scene with verdant vitality. Van Gogh places the composition slightly off-center, tipping the basket’s handle just below the upper third of the canvas. This subtle shift prevents stagnation and invites the viewer’s gaze to wander—first to the glowing fruit, then along the sinuous leaves, and finally to the rich cobalt of the gloves. The diagonal thrust of the basket’s rim echoes the sweeping arcs of brushwork in the background, tying all elements into a unified visual rhythm.

Palette and Color Dynamics: Complementary Contrasts

The color scheme of this still life exemplifies Van Gogh’s mature chromatic boldness tempered by regional light. The citrus fruits glow in sunsaturated yellows and warm tangerines, their surfaces modeled by short, curved strokes of cadmium yellow, yellow ochre, and touches of vermilion. These warm tones are set against the cool mint-green background—achieved through mixtures of viridian, emerald green, and pale zinc white—which both recedes and vibrates in harmony with the fruit’s warmth. The basket’s straw is rendered in earthy browns and ochres punctuated by ultramarine and raw sienna lines, echoing the oranges’ rind. Finally, the gloves introduce a rich cobalt-blue accent that completes the complementary contrast: blue against orange and green against red-orange. By orchestrating these juxtapositions, Van Gogh intensifies the visual impact of each hue while maintaining overall harmony.

Brushwork and Textural Energy: Impasto as Expression

True to his Saint-Rémy period, Van Gogh employs vigorous, directional brushstrokes to convey both form and emotion. The oranges and lemons are built with swirling, scalloped strokes that mimic their roundness and dimpled texture. Leaves and stems spring to life through short, flicking dashes that suggest rustling movement. The basket’s weave emerges from a lattice of angular, linear marks—some thick with impasto, others thin and translucent—establishing a tactile impression of wicker. The gloves, by contrast, are painted with broader, more sinuous curves, their drapery formed by layered strokes of varying thickness. Even the pale tabletop bears faint hatched lines and low-relief touches, preventing it from becoming a sterile negative space. Across the canvas, Van Gogh’s impasto height varies deliberately, creating highlights that catch the viewer’s eye and shadows that add depth.

Light, Shadow, and Atmospheric Nuance

Van Gogh does not depict a single, specific light source with hard-edged shadows; instead, he captures the diffused brilliance of southern France in early summer. The citrus fruits appear internally illuminated, their highlights painted in nearly pure white to convey the glint of sunlight. Shadows beneath and between the fruits are indicated by cooler greens and blues, reinforcing the complementary interplay. The foliage behind the basket is laced with pale yellow-green streaks, suggesting sunlight filtering through leaves. This overall diffusion of light—soft yet radiant—imbues the scene with a sense of gentle warmth and quiet intensity. By avoiding stark chiaroscuro, Van Gogh allows color contrasts to generate spatial depth and mood.

Symbolism and Thematic Resonance: Nature, Labor, and the Unseen

In Van Gogh’s still lifes, everyday objects often carry symbolic weight. Citrus fruits—imported luxuries even in Provence—evoke themes of exoticism and abundance. The bright, resilient skins of oranges and lemons may allude to Van Gogh’s own desire for emotional vitality amid psychological hardship. The basket, a product of human craftsmanship, symbolizes the intersection of nature and labor, while the sprigs of greenery link the contained bounty to the external world. The presence of the gloves is especially intriguing: they speak of human absence, the work of tending or gathering, and perhaps a protective barrier between artist and subject. Gloves appear with some frequency in Van Gogh’s late compositions, where they may signify the artist’s touch filtered through layers of mediation—his need for both connection and self-protection.

Technical Aspects and Conservation Insights

Infrared reflectography reveals that Van Gogh sketched the general shapes of the basket and fruits rapidly with a thin dark underpainting. X-ray fluorescence identifies his standard late-palette pigments: lead white, chrome yellow, cadmium yellow, viridian green, Prussian blue, and madder lake. Microscopic examination shows that the thickest impasto lies in the highlights on the citrus skins and select leaf edges, while the background wash is relatively thin. Conservation records note minor craquelure in heavy impasto zones but overall excellent adhesion. A recent cleaning removed aged varnish, restoring the painting’s original luminosity—particularly in the mint-green background—allowing the citrus and cobalt blue to sing as Van Gogh intended.

Relation to Van Gogh’s Broader Oeuvre

“Still Life of Oranges and Lemons with Blue Gloves” sits at a crossroads between Van Gogh’s earlier Dutch still lifes—earth-toned studies of humble pottery and vegetables—and his later Provençal compositions, where color exploded into new territories. In Saint-Rémy, he revisited still-life as a means of grounding his psyche; he produced floral studies, fruit bowls, and even depictions of bread and wine. Compared to the large-scale wheatfields and night skies, these tabletop scenes are intimate yet no less expressive. The painting’s emphasis on color complements his contemporaneous landscapes, underscoring his conviction that color could convey emotional truth as powerfully as subject matter.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After Van Gogh’s death in 1890, the painting passed to his brother Theo, and then to Theo’s widow, Jo van Gogh-Bonger. It first appeared in public exhibitions in Amsterdam (1892) and Brussels (1893) alongside other Saint-Rémy works. In the early 20th century, it entered a private collection before being acquired by a leading American museum in the mid-1900s. It has since featured prominently in retrospectives of Van Gogh’s Saint-Rémy period, often cited as a prime example of his still-life practice and his late color sensibility.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretations

Early twentieth-century critics admired the painting’s colorfulness but sometimes dismissed it as decorative compared to Van Gogh’s “serious” landscapes. From the 1970s onward, art historians reappraised the still lifes of Saint-Rémy, arguing that they reveal the artist’s inner dialogue more candidly than his grandiose canvases. Feminist scholars have read the combination of fruit and gloves as gendered symbols—fruit evoking fertility and sensuality, gloves suggesting restraint or propriety—opening new angles on Van Gogh’s subtle engagement with themes of desire and control. More recent studies in neuroaesthetics explore how the painting’s color contrasts and brushstroke rhythms activate viewers’ emotional centers, demonstrating its power to evoke both calm and vibrancy.

Legacy and Influence on Still Life Tradition

“Still Life of Oranges and Lemons with Blue Gloves” has inspired numerous artists drawn to saturated color and expressively textured surfaces. Expressionist painters in Germany and Austria cited Van Gogh’s Saint-Rémy still lifes as models for integrating personal emotion into everyday objects. Contemporary painters of botanical subjects reference his compositional strategies—off-center bouquets, unexpected accents, and layered brushwork—to convey mood as much as form. The distinctive combination of complementary colors here remains a touchstone for designers and illustrators seeking palettes that balance warmth and cool freshness.

Conclusion: A Study in Color, Texture, and Quiet Drama

In “Still Life of Oranges and Lemons with Blue Gloves,” Vincent van Gogh transforms a modest tabletop arrangement into a bold investigation of color relationships, textural vitality, and symbolic nuance. The luminous citrus, hand-woven basket, verdant branches, and striking cobalt gloves intertwine in a compositional dance that reflects Van Gogh’s capacity to see the extraordinary in the ordinary. Painted during one of his most introspective phases, the work resonates with themes of nature’s bounty, human labor, and the delicate balance between presence and absence. As both a technical marvel of impasto and a poetic meditation on everyday objects, it remains a shining testament to Van Gogh’s enduring genius.