Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Francisco de Zurbaran’s Still Life of 1633

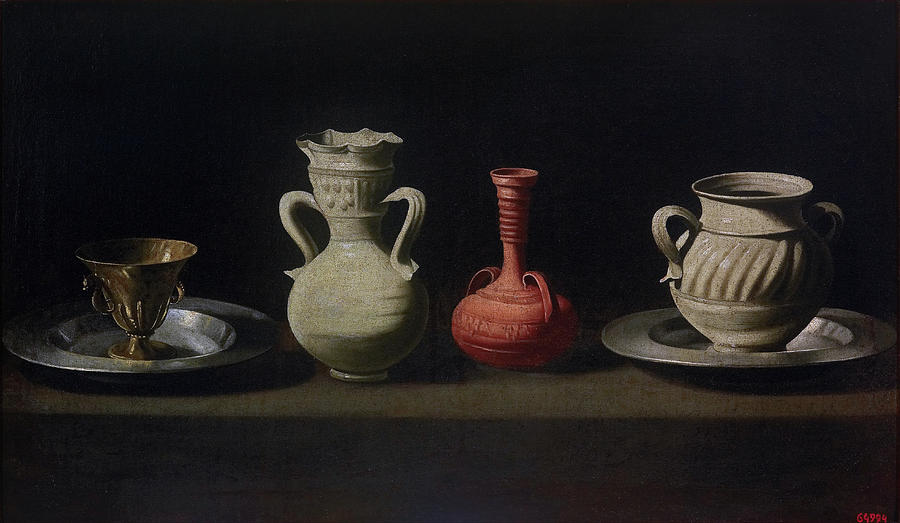

Francisco de Zurbaran’s “Still Life” from 1633 is a deceptively simple painting. Four vessels stand in a row on a narrow ledge against a deep black background. From left to right, a golden chalice sits on a silver plate, followed by a pale two handled ceramic jug, a small red earthenware bottle, and another pale jug resting on a second silver plate. Nothing else interrupts the silence. No fruit, flowers or insects appear, only these four objects, precisely spaced and brilliantly lit.

Despite its restraint, this still life holds a powerful presence. Its quiet symmetry, the careful modeling of each vessel and the stark contrast between light and darkness create a sense of stillness that is almost meditative. The painting is an outstanding example of Spanish bodegón painting, where humble objects become subjects for contemplation. At the same time, the work hints at symbolic meanings that would have resonated with seventeenth century viewers, particularly within a religious and monastic environment.

Historical Context and Zurbaran’s Still Life Tradition

Zurbaran is best known for his images of monks, saints and martyrs, but he also produced a small group of still life paintings that reveal another facet of his art. In early seventeenth century Spain, still life had become an important genre, especially in Seville. Artists such as Juan Sánchez Cotán had developed a severe, geometric style in which fruits, vegetables and kitchen utensils were arranged against dark backgrounds, creating images that felt at once real and symbolic.

Zurbaran adopted this bodegón tradition and adapted it to his own sensibility. His still lifes tend to be sparse and architectonic, focusing on a few objects rendered with extraordinary care. The 1633 “Still Life” belongs to this group. It may have been intended for a monastic refectory or a private devotional space. In such settings, ordinary objects could acquire spiritual significance, reminding viewers of simplicity, order and the presence of God in material things.

The date of 1633 places the painting in a period when Zurbaran had already established his reputation as a major painter in Seville. Commissions from religious orders dominated his work, and his style was marked by strong contrasts of light and shadow, solid forms and a contemplative tone. These qualities are clearly visible in this still life.

Composition and Spatial Structure

The composition of the painting is remarkably disciplined. A single horizontal ledge runs across the lower part of the canvas, supporting the four vessels. The objects are placed in an almost mathematical arrangement, with roughly equal spacing between them. The eye moves from left to right, tracing a rhythm of differing heights, shapes and materials.

On the far left, the golden chalice is the smallest of the group, but it gleams with warmth and reflects the light sharply. It stands inside a shallow silver plate whose broad rim catches a cooler sheen. Next to it rises the pale, double handled jug with a wide belly and an ornate, scalloped rim. The contrast in size and material between the metal chalice and the ceramic jug creates a dynamic interplay.

At the center stands the red earthenware bottle, slender in neck and rounded at the base. Its bright color breaks the otherwise limited palette and becomes a visual pivot between the pale clay vessels and the metallic tones. To the right, the second pale jug echoes the form of the first but with a slightly different profile, again resting on a silver plate.

The background remains completely dark, with no indication of walls, corners or windows. This lack of spatial context pushes the objects forward and gives them an almost sculptural presence. The ledge appears shallow, emphasizing the thin layer of space in which the still life unfolds. This spatial compression focuses attention on the shapes themselves rather than on any surrounding environment.

Light, Shadow and the Tenebrist Atmosphere

Light is crucial to the mood of the painting. A single source of illumination, coming from the left, strikes the vessels and plates, leaving the background and the far edges of the ledge in deep shadow. This tenebrist approach, influenced by Caravaggio and his followers, was a hallmark of Zurbaran’s style. Here it transforms simple pottery into luminous forms that emerge from darkness like apparitions.

The chalice on the left gleams with bright highlights along the rim and stem. Its interior reflects the light in a soft, golden glow. The silver plate beneath it shows a mixture of sharp reflections and broad diffused areas, conveying the different ways metal surfaces respond to light. The pale jugs receive a softer illumination, which reveals their textures and subtle imperfections, including small cracks or irregularities in the glaze. The red bottle displays a more matte surface, with light emphasizing its rounded volume and the ridges along its neck.

Shadows play an equally important role. Each vessel casts a shadow on the ledge, anchoring it firmly in space. The backgrounds behind the objects shift from near black to very dark brown, but the transitions are so gradual that the overall effect is one of enveloping darkness. This darkness is not threatening. Instead it functions as a kind of void that allows the viewer to concentrate on the forms bathed in light.

The controlled interplay of light and shadow gives the painting a contemplative quality. It suggests that understanding comes through illumination, that things reveal their true form when touched by light. In a religious context, such imagery could be associated with divine grace or spiritual enlightenment.

Forms, Materials and the Sensuality of Surfaces

One of the great pleasures of this still life lies in the way Zurbaran differentiates materials. Each vessel not only looks distinct in shape but also in substance. The golden chalice conveys the cool hardness of metal. Its polished surface reflects the surrounding light and the curve of the plate beneath it. The silver plates appear slightly less reflective, with a softer luster that hints at wear and age.

The pale ceramic jugs have a matte finish that contrasts with the sheen of the metal objects. Zurbaran models them with small shifts of tone that suggest the thickness of the clay walls and the weight of the vessels. Their handles curve outward with a sense of functional strength, while decorative ridges around their bodies introduce gentle rhythms of light and shadow.

The red bottle, perhaps made of terracotta, sits between these worlds of metal and pale clay. Its warm color and dense form give it an almost bodily presence. The artist subtly marks its surface with faint lines and variations, suggesting that it may be handmade rather than factory perfect. The neck of the bottle rises slender and ribbed, caught by the light in a series of tiny highlights.

By paying such close attention to the tactile qualities of each material, Zurbaran invites the viewer to imagine how these vessels might feel if touched: the cool smoothness of metal, the slightly rough texture of clay, the weight of a full jug or the empty hollowness of a vessel waiting to be filled. This sensuality of surfaces is not gratuitous. In the context of a monastic still life, it reinforces the idea that the created world is good and worthy of respectful observation.

Order, Symmetry and the Search for Harmony

The arrangement of the vessels reveals a deep concern for order and balance. The two pale jugs on either side of the red bottle create a kind of symmetrical frame. The golden chalice, though distinct in material and scale, forms a counterpart to the red bottle in terms of height. Together, the four objects produce a harmonious sequence of volumes and colors.

This deliberate ordering reflects ideals of harmony that were central to Baroque art and to religious thought of the period. In a world often marked by political and social turmoil, the orderly arrangement of objects on a table could symbolize a higher, divine order underlying the apparent chaos of daily life. For monks or devout laypeople contemplating this painting, the calm alignment of vessels might evoke the ordered structure of monastic life, governed by rules and rhythms that lead toward inner peace.

The precise spacing between the objects also contributes to this sense of measured harmony. None of the vessels touch. Each has its own space, yet they belong to a single composition. This balance between separation and unity mirrors the ideal of community in monastic settings, where individuals retain their identity while participating in a shared spiritual project.

Possible Symbolic Meanings

While the painting works beautifully as a purely formal study, many viewers and scholars have discerned symbolic meanings in the choice and arrangement of objects. In a deeply Catholic culture, everyday items often carried layers of spiritual significance.

The golden chalice immediately suggests liturgical associations. It recalls the chalice used for the Eucharist at Mass, the vessel that holds the consecrated wine believed to become the blood of Christ. Placed on a silver plate, it could allude to the paten used for the host. These associations point to the central sacrament of Christian worship and the theme of spiritual nourishment.

The pale jugs may symbolize vessels of water or wine, substances essential for ritual and daily life alike. In Christian symbolism, water is linked to baptism and purification, while wine is linked to joy and sacrifice. The fact that there are two similar jugs could point to the dual nature of Christ, human and divine, or to the balance between active and contemplative life in religious communities.

The red bottle stands out not only visually but symbolically. The color red is often associated with love, sacrifice and the Holy Spirit. This small vessel between the larger ones could represent the presence of Christ or the burning heart of charity that unites all things. Its central position reinforces this interpretation.

Even the number of objects may carry significance. Four vessels could allude to the four Gospels or the four cardinal virtues. The two plates beneath the chalice and the rightmost jug might represent a grounding in sacramental practice and daily bread.

While none of these interpretations can be proven with certainty, the painting’s context in a religious society makes it plausible that viewers would have read spiritual meanings into such a carefully composed arrangement.

Relationship to Spanish Bodegón Painting

Compared to still lifes from the Netherlands, which often feature overflowing fruit, elaborate glassware and reflective surfaces, Spanish bodegones tend to be more austere. They favor simple objects, limited color ranges and a strong emphasis on humility. Zurbaran’s “Still Life” exemplifies this aesthetic.

Like earlier bodegones by Sánchez Cotán, the painting uses a dark background and a shallow ledge to isolate its objects. The emphasis lies not on abundance but on clarity. Each vessel is fully visible and illuminated, allowing the viewer to study it in silent concentration. The simplicity of the composition encourages an almost meditative engagement.

At the same time, Zurbaran’s painting shows a softer handling of light and form than some of his predecessors. The transitions between light and shadow are gradual rather than abrupt, and the objects seem to breathe within the dark space rather than stand in stark isolation. This gives the work a slightly more humane and gentle character, consistent with the atmosphere of many of his religious paintings.

A Meditative Still Life for Contemplative Viewers

The overall effect of Zurbaran’s “Still Life” is one of contemplative calm. There is no narrative to follow, no dramatic event. Instead, the viewer is invited simply to look, to let the eye travel slowly over the shapes and surfaces, to observe the play of light and shadow. This kind of looking mirrors the practice of meditation in religious life, where one concentrates on a single theme or image in order to deepen understanding and devotion.

In a monastic setting, such a painting could serve as a visual anchor during meals or periods of quiet reflection. The vessels might remind the viewer of the act of serving and being served, of receiving nourishment with gratitude, of the connection between the material and spiritual dimensions of life. The stillness of the scene encourages inner stillness.

Even for contemporary viewers outside a religious context, the painting offers a space of rest. In a world saturated with images and information, the disciplined simplicity of four vessels on a dark background can feel refreshing. Zurbaran shows that painting does not need spectacular subjects to be profound. The humble still life becomes a doorway to questions about value, presence and the beauty of ordinary things.

Legacy and Modern Appreciation

Today, Zurbaran’s still lifes are highly valued for their quiet intensity and technical excellence. “Still Life” of 1633 stands out among them as a masterpiece of minimalism long before the term existed. Modern audiences often admire its almost abstract qualities, the way it reduces the scene to a few essential shapes and tones while still conveying a strong sense of reality.

The painting also serves as an important bridge between early modern devotional art and later explorations of the object in painting. Artists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who focused on simple objects, from Cézanne’s apples to Morandi’s bottles, can be seen as distant heirs to the concentrated vision that Zurbaran displays here. His still life proves that a limited set of forms, carefully observed, can sustain endless contemplation.

Conclusion

Francisco de Zurbaran’s “Still Life” of 1633 is a quietly powerful work in which four vessels arranged on a ledge become the focus of intense visual and spiritual attention. Through careful composition, dramatic yet controlled lighting and meticulous rendering of surfaces, the artist transforms simple objects into a meditation on order, material beauty and perhaps sacramental meaning. The golden chalice, pale jugs and red bottle stand in silent relation to one another, inviting viewers to ponder their forms, textures and possible symbolism.

Whether viewed as a religious image or as a masterful exercise in still life painting, the work demonstrates Zurbaran’s ability to infuse the everyday world with a sense of the sacred. Its disciplined simplicity and luminous presence continue to resonate, offering a moment of quiet reflection to anyone who pauses before it.