Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

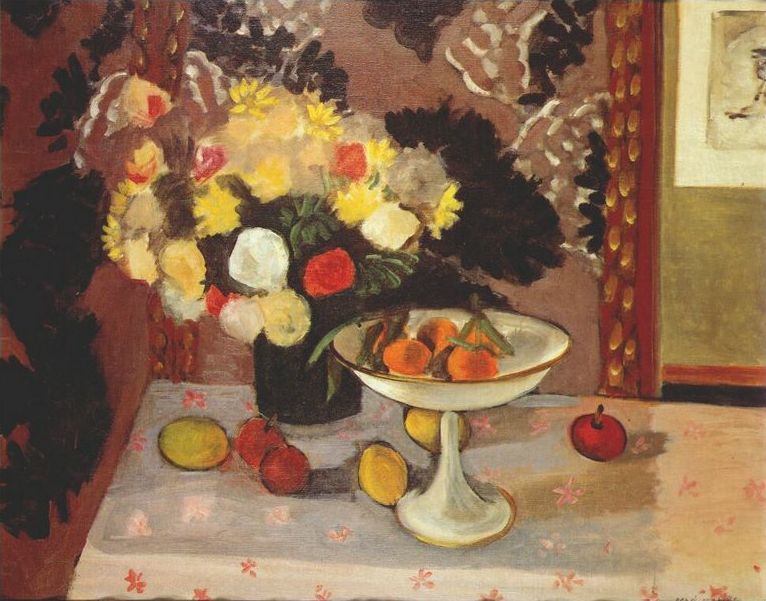

Henri Matisse’s “Still Life (Bouquet and Compotier)” from 1925 condenses the ambitions of his Nice period into a tabletop theater of color, rhythm, and calm. A pedestal bowl of bright fruit, a dense bouquet of garden flowers in a black vase, a patterned wall hanging, and a pale cloth scattered with tiny pink motifs are arranged so that every element both asserts itself and contributes to a larger harmony. The painting is intimate in scale and subject, yet its orchestration of hue, contour, and pattern feels expansive. Matisse does not try to imitate how the eye records a room; he composes a world where color and shape are the primary actors, and where flowers, fruit, and fabrics speak a shared decorative language.

The Still Life Tradition Reimagined

Still life offered Matisse a laboratory for testing pictorial relations without the complications of narrative. In this canvas he revisits the genre with the maturity of the 1920s, when he had refined the audacity of Fauvism into a poised, musical classicism. The bouquet and compotier are traditional motifs—the abundance of nature gathered indoors, the fleetingness of blooms paired with the comparative durability of fruit—but their meaning is carried less by symbolism than by the way they are painted. The picture proposes that the most ordinary studio props can form a complete, modern world if they are tuned to one another with care.

Composition and the Choreography of the Table

The composition is anchored by two masses: the bouquet at left and the white compotier at center-right. They sit on a tabletop that fills the lower half of the canvas and tilts gently toward the viewer, a device that compresses space and turns the table into a stage. The bouquet’s dark vase, nearly cylindrical, supplies vertical weight; its flowers billow outward in a cloud whose irregular edge vibrates against the patterned wall behind. The compotier, raised on a stem, introduces an elegant counterweight: a shallow disk that holds oranges while catching light along its rim. Scattered fruits on the cloth keep the eye circulating, while a framed picture at the far right nudges the scene back into the world of art-making, reminding us this is a painter’s room, not a replicating camera.

Rhythm and Balance Between Bouquet and Bowl

The dialogue between bouquet and bowl structures the painting’s rhythm. The bouquet is a cluster of small, soft units—petals, buds, and leaves—fused into an airy mass. The bowl, by contrast, offers large, smooth forms: the round of the dish, the orbs of the oranges, the straight stem. The two shapes create alternating currents of soft complexity and simple clarity. Matisse positions them so that the bouquet’s outermost flowers lean toward the bowl, while the bowl’s fruit glows back in response. This call and response is reinforced by the scattered fruits near the base of the vase, which bridge the two principal actors and keep the eye moving in a gentle ellipse.

Color as the Primary Architecture

Color in “Still Life (Bouquet and Compotier)” is calibrated with exquisite restraint. The background is a warm mauve-brown enlivened by black leafy silhouettes and lighter arabesques, a tapestry-like field that both holds and heightens the central objects. Against it the bouquet blooms in creams, pale yellows, soft whites, and occasional reds, their lightness intensified by the black vase. The tablecloth is a cool, light gray with small pink blossoms, a quiet plane that reflects and softly cools the warmer tones above. The compotier’s dish reads as white but is actually a delicate mixture of blue, gray, and warm notes, so it appears luminous rather than chalky. The oranges glow as concentrated kernels of warmth, and the scattered fruits—yellow, red, greenish—extend the palette without breaking it. Nothing is shrill; everything is tuned to produce a state of steady radiance.

Pattern as Structure, Not Ornament

The Nice period is often called decorative, but pattern here is not superficial embellishment; it is structural. The wall hanging behind the table organizes the background into a rhythm of dark and light shapes that counterpoint the bouquet’s forms. Its leaflike silhouettes and pale arabesques echo the organic shapes of petals and stems while remaining distinctly flat. The tablecloth’s tiny blossoms distribute small touches of pink across a large light plane, preventing it from becoming empty while maintaining calm. These patterns do not describe a particular fabric with ethnographic fidelity; instead, they act as measured pulses that keep the composition balanced and alive.

The Authority of Contour and the Economy of Drawing

Matisse’s drawing is decisive and economical. The compotier’s ellipse is firm but not mechanical; it breathes like a hand-drawn curve, perfectly imperfect. The bouquet is contained not by hard outlines but by an edge that stiffens and releases in response to the masses of flowers. The scattered fruits are defined by quick, rounded lines that give just enough information for the eye to complete the form. Even the frame at right, with its narrow gold edge, is drawn with a steady hand that asserts flatness while acknowledging depth. This kind of drawing moves with the rhythm of the painter’s looking; it feels as if the picture has been composed in time, not constructed from a diagram.

Light, Atmosphere, and the Softened Shadow

Light in this painting is diffuse and interior. There are no theatrical highlights or deep cast shadows; instead, forms are modeled with subtle shifts of temperature and value. The compotier catches the most obvious glimmer—a pale band along the rim and a cool reflection within the bowl—but even here the sheen is gentle, more satin than gloss. The bouquet seems lit from within, its whites never harsh, its yellows dissolving into cream at the edges. This treatment produces a serene atmosphere in which objects hold their places without competing for attention. The effect is less like a momentary snapshot than like a sustained chord.

Space, Depth, and the Productive Flatness of the Surface

Matisse handles space with a productive ambiguity. The tabletop recedes enough to locate objects in relation to one another, yet it also reads as a flat field where motifs are placed like notes on a staff. The wall hanging is emphatically planar, pressing its pattern forward so that it interacts with the bouquet at the same level as the objects themselves. The framed image at the right hints at deeper space while its gold edge insists on the painting’s surface. This balance—between inhabitable interior and decorated plane—is a hallmark of Matisse’s mature style and gives the still life its distinct modernity.

The Bouquet as Cloud and the Intelligence of Touch

The bouquet is one of Matisse’s most persuasive demonstrations of how paint can record softness without fuss. Each blossom is rendered in a few strokes that suggest volume through overlapping patches rather than detailed petals. Creams and yellows feather into one another; occasional reds and whites punctuate the mass to keep it lively. The black vase, nearly featureless, operates as a foil: a deep, absorptive shape that allows the color cloud above it to glow. Brushwork remains visible, but not as display; it serves the sensation of light moving through clustered forms.

The Compotier as Counterpoint and Pedestal

The compotier is both a functional dish and a sculptural form. Its raised stem adds a vertical accent to a composition dominated by horizontal tabletop and background pattern. The shallow bowl cradles oranges whose stems and leaves provide agile green marks that offset the warmer hues. Because the compotier is white, it becomes a kind of reflector, picking up nearby colors and softly returning them. It also introduces a classical note: the pedestal form evokes antiquity, connecting Matisse’s modern decorative language to older ideals of balance and clarity.

The Scattered Fruits and the Pace of Looking

The single apple at the far right, the lemon tinged with green near the compotier’s foot, the small red fruit at center-left—these are not afterthoughts but deliberate tempo markings. They slow the eye, establishing waypoints across the table so that the viewer’s attention does not race from bouquet to bowl and stop. Their shadows are quiet but firm, providing enough weight to anchor them without disturbing the overall lightness. Each fruit is also a miniature study in color relations: a red that leans warm against the gray cloth, a yellow that absorbs a whisper of violet from surrounding tones, a green cast that nudges the palette cooler for a moment before warmth reasserts itself.

The Framed Image and the Self-Awareness of the Interior

At the painting’s right edge, a partial framed work peeks into view. It is not legible as a specific subject; it reads as a pale rectangle bordered by gold. Its presence is crucial. It reminds us that this still life is set in the space of art, not simply in a domestic dining room. The frame within the frame acts like a mirror of the canvas itself, another flat surface carrying marks. It contributes a vertical accent and a sliver of gray wall that cools the surrounding warmth. Most importantly, it situates the bouquet and compotier as deliberate arrangements, the outcome of a painter’s attention rather than happenstance.

The Nice Period Ethos of Calm Discipline

This still life exemplifies the Nice period ethos: a commitment to calm that is anything but lazy. The calm comes from disciplined decisions about intervals and weights, not from the absence of energy. The background pattern is bold but softened; the colors are bright but moderated; the drawing is clear but never rigid. Matisse sought an art that could bring restfulness without dullness, a visual equivalent to slow music. In “Still Life (Bouquet and Compotier),” the viewer feels that ethos immediately: the room’s warmth, the measured spacing of forms, the suffused light that makes objects seem to exhale.

Dialogues with Earlier Works

The painting converses with earlier Matisse still lifes such as “Harmony in Red (The Red Room)” and “The Dessert: Harmony in Red,” where a table, a patterned wall, and fruit are fused into a nearly continuous field. In those daring canvases pattern devours space. Here, a decade later, Matisse finds a gentler resolution: pattern retains its forward pressure, but objects keep enough volume to read as things in a room. It also speaks to works like “The Goldfish,” where a white compotier-like container served as a luminous anchor. The 1925 still life distills these experiences into a poised, chamber-scale performance.

The Sensuous Intelligence of Paint Handling

The pleasure of this painting lies not only in what is depicted but in how it is made. The cloth is brushed thinly so the weave of canvas breathes through, giving the surface a textile-like presence. The compotier’s stem receives thicker, creamier paint to suggest porcelain; the oranges are built with warmer, semi-opaque layers that hold light. The background’s black leaves are laid in with confident, flat strokes that assert silhouette over modeling. This sensuous intelligence—choosing just enough paint and the right kind of touch for each passage—allows the whole to feel lucid and light.

Time, Ripeness, and the Poetics of the Table

Still life often carries a quiet meditation on time. Here, the bouquet is in full, even overripe bloom; the oranges are at their peak; the small scattered fruits vary in maturity. Nothing is decaying or dramatic, yet the picture suggests the delicate interval when things have reached their sweetest state. Matisse’s calm does not deny the fleeting nature of such moments; it honors them by holding them in a suspended present where looking can be prolonged. The tabletop becomes a small stage for ripeness, a celebration of the day’s middle hour when light is steady and colors are true.

Modern Classicism and Lasting Resonance

Although the painting is rooted in the everyday and refuses academic grandiosity, it aspires to a modern classicism. Its structure is clear, its relations legible, its mood balanced. The bouquet and compotier behave like classical orders—the organic and the architectural—held in equilibrium. This is not a revival of the past but a contemporary answer to it: clarity without stiffness, harmony without pedantry. Such qualities give the work a lasting resonance. It reads as fresh in a kitchen as in a museum because its pleasures are structural, not fashionable.

Why the Painting Endures

“Still Life (Bouquet and Compotier)” endures because it realizes a promise central to Matisse’s art: that attentive arrangement can elevate ordinary things into a stable world of feeling. The picture offers warmth without heat, pattern without noise, and clarity without dryness. It invites the viewer to move slowly from the cool rim of the white bowl to the pulse of the oranges, from the soft cloud of the bouquet to the quiet blossoms on the cloth, from the planar insistence of the wall to the glimmer of the frame. With each circuit the painting yields new relations and confirms its essential truth—that harmony, patiently composed, is inexhaustible.