Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

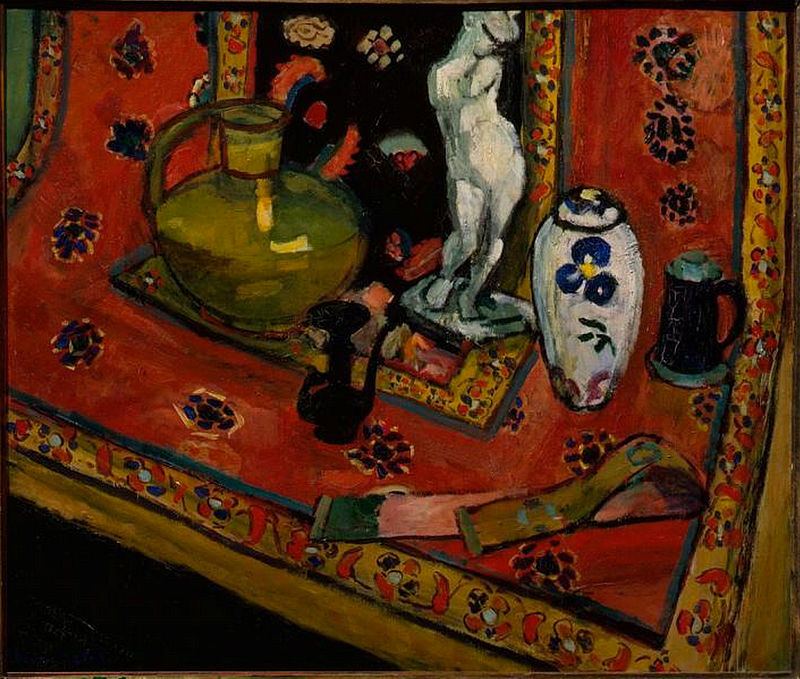

Henri Matisse’s Statuette and Vases on Oriental Carpet (1908) is a dazzling demonstration of how a still life can become an arena where color, pattern, and form contend on equal terms. Spread across a shallow tabletop that is almost completely engulfed by a red Oriental carpet, an ensemble of objects gathers: a pale statuette on a small patterned platform, a squat green glass jug catching highlights along its shoulder, a slender black ewer, a white vase with blue flowers, and a dark mug with a turquoise saucer. A folded ribbon of fabric lies along the lower edge like a resting brushstroke. Nothing in the scene is neutral. The carpet’s saturated red, studded with floral medallions and hemmed by a yellow border, turns the setting into a chromatic stage, while Matisse’s assertive outlines and angled viewpoint collapse depth and fuse the objects into a single, pulsing surface. The painting is a manifesto for a modern interior in which decoration is structure, color is architecture, and studio artifacts become actors in a carefully tuned play.

Historical Context

By 1908 Matisse had moved past the first blaze of Fauvism and was searching for new balance. The shock of pure, unblended color had done its work; now he sought clarity and integration—how to keep color’s intensity without surrendering form. Parallel to this search, Matisse increasingly populated his studio with textiles, ceramics, and small sculptures from different cultures, most notably from the Islamic world. Oriental carpets, with their intrinsic planar logic and complex borders, became central to his pictorial thinking. They offered a ready-made field of color and pattern that could stand in for the floor, the wall, and the table, blurring distinctions between background and support. Statuette and Vases on Oriental Carpet exemplifies this fusion. It is not a document of a domestic table; it is a rehearsal room for the larger decorative interiors that would soon culminate in works like The Red Studio, where furniture and objects float in pure fields of color.

Composition and Spatial Design

The composition is built from strong diagonals that tip the tabletop toward the viewer, denying deep recession and collecting the objects against the surface. The lower border of the carpet slices across the picture like a stage front. The small platform beneath the statuette tilts at a slightly different angle, creating a counter rhythm that animates the middle ground. Matisse positions the green jug and the white vase so that they flank the sculpture like attentive companions, while darker vessels punctuate the red field with notes of near-black. Overlaps do the work of space: the jug hides part of the ewer, the statuette interrupts the carpet pattern, the white vase grazes the border. Rather than mapping depth through classical perspective, Matisse constructs a shallow, breathable plane where objects are held in place by color contrasts and firm contours.

The Oriental Carpet as Architecture

No element carries more structural weight than the carpet. Its saturated crimson is a load-bearing wall, a roof, and a floor. The yellow border, filled with sprouting forms and scalloped motifs, acts like a frame within the frame, keeping the red in tension and guiding the eye around the perimeter before returning it to the objects. Scattered rosettes, paisleys, and leafy stamps pierce the red, preventing it from becoming a monotone field and establishing a pulse that continues in the decorations on the platform under the statuette. Because the carpet is both setting and ornament, it collapses the usual distinction between figure and ground. Everything sits on it and in it at once, producing the characteristic Matisse paradox: the painting reads as a coherent space and as a woven tapestry simultaneously.

Palette and Color Strategy

Matisse orchestrates a small but potent palette. The red of the carpet dominates, but it is not a single red; it modulates from vermilion to darker, near-burgundy passages, especially toward the upper left where the tonality deepens. The yellow border leans toward ocher with flecks of orange and cooler accents that prevent heat from overwhelming the scene. Against this warm field, the objects deploy a sequence of complementary answers. The green jug is a study in controlled reflection, its shoulder catching a lemon highlight while its belly descends into olive shadow. The white vase carries cobalt blue flowers and a green stem, a cool chord that freshens the red around it. The small black ewer and dark mug contribute gravity and calm, their blue-green saucers or halos breaking the red in measured intervals. The statuette remains pale, with touches of blue-gray and warm brown; its neutrality is an optical hinge that keeps the more saturated objects from fighting. Through these calibrated oppositions Matisse achieves both vibrato and repose.

Contour and Drawing

Bold, dark contours run throughout the painting, encircling objects and pattern motifs with a calligrapher’s certainty. These lines are neither timid nor mechanical. They thicken at curves, thin along straights, and occasionally fray where a loaded brush met the tooth of the canvas. Around the jug, a steady outline describes the handle’s loop, the lip’s notch, and the broad shoulder. The statuette’s profile is cut with a sculptor’s decisiveness, especially along the back and leg, where a single line articulates the body’s torque. On the white vase, the black collar at the neck and the crisp drawing of the floral emblem are simultaneously decorative and structural. Contour here is not a cage for color; it is a binding agent that allows strong, flat hues to coexist without dissolving into chaos.

The Statuette: Painting Meets Sculpture

The small white nude poised on a patterned plinth is a keystone of the composition and a clue to Matisse’s method. He often painted sculptures in his studio because they offered a distilled anatomy already translated into plane and mass. The statuette’s surfaces turn not through soft shading but through abrupt shifts of value—cooler blue-greens on the shadowed side, warmer notes on the lit side—echoing Matisse’s own sculptural practice, where volumes are established by decisive facets. Its whiteness also serves a tactical function: set against red and yellow, it becomes a quiet star, a place for the eye to rest before reentering the storm of pattern. The statuette’s pose—contrapposto with a twist—injects a human rhythm into the array of vessels and textiles, bridging object and body, art and artifact.

Objects as Characters

Each vessel brings a distinct personality to the stage. The green glass jug is capacious and serene, its transparency suggested by subtle shifts of tone and by the way the carpet’s edge seems to skim beneath its belly. The black ewer, small but emphatic, is all silhouette; it anchors the red field like a bass note. The white vase with blue flowers is an emissary from a different temperature zone, bright and cool; its simple ornament repeats the carpet’s floral theme at a larger scale. The dark mug at the right margin, paired with a turquoise saucer, completes a march of values from light to dark that balances the composition. Even the folded ribbon of fabric curling at the bottom edge functions as a character—pliable, painterly, and frankly abstract compared to the more defined ceramics.

Pattern, Ornament, and Decorative Intelligence

Matisse’s genius for pattern lies in his ability to let ornament carry structure. The carpet’s border repeats along three sides, its motif density increasing and decreasing like a musical dynamic to match the needs of the picture. The small patterned platform beneath the statuette reprises the border’s language on a new scale, aligning it with the carpet while setting it apart as a discrete stage for the sculpture. The flowers painted on the white vase echo the scattered rosettes in the field, creating a system of rhymes. Even the smudges of color on the fabric strip at the bottom feel like miniature abstracts of the surrounding ornaments. Pattern is never a passive backdrop; it is the grammar that assembles independent things into a single visual sentence.

Light Without Illusionism

Traditional still life often depends on a directional light source that casts shadows and models forms. Matisse declines that apparatus. Light here is a condition generated by color relationships. The jug feels luminous because yellow-green sits against red; the statuette appears bathed in cool illumination because blue-gray notes interrupt its warm passages; the white vase shines because it is sharply edged against a darker background. Cast shadows are hinted at rather than measured; they are chromatic swells more than geometric facts. This strategy maintains the surface’s integrity while still giving each object convincing presence.

Brushwork and Material Surface

The painting’s surface reveals the speed and decisiveness of its making. The red field is laid with broad, robust strokes that leave small ridges and gaps where underlayers peek through. The yellow border is painted more opaquely, its motifs dropped in with quick, loaded dabs that retain their relief. On the objects, the brush follows the form’s curvature—the jug’s roundness, the statuette’s contour—so that touch and structure agree. Portions of the carpet near the lower right are scumbled, allowing black underpaint to breathe through and deepen the red, a subtle reminder that color in Matisse is built as much by subtraction as by addition.

Space, Flatness, and the Modern Plane

One of the painting’s lasting achievements is its reconciliation of space with flatness. The scene reads as a believable tabletop, yet the carpet’s dominance and the compressed angles of the borders keep the eye close to the surface. Matisse refuses the window-like illusion of classical perspective and instead offers a woven plane where objects and patterns jostle for primacy. The result is a modern space that does not pretend to be a hole in the wall; it is a designed surface alive with pushes and pulls—near not because it recedes correctly, but because its colors and edges demand proximity.

Cross-Cultural Conversation

The title’s “Oriental” carpet signals the broader cultural conversation at work. Matisse collected North African and Middle Eastern textiles not as trophies but as teachers. From them he learned that pattern can define space and that color can be unblended and yet harmonious. In this painting, the carpet’s vocabulary sets the rules for every other object: the statuette conforms by standing on a patterned platform; the white vase contributes its simplified floral sign; the green jug’s measured highlights and the black ewer’s silhouette echo the rug’s alternation of bright fields and dark outlines. The painting becomes an homage to textile intelligence—how woven designs generate order—and a demonstration of how painting can absorb that logic without merely imitating fabric.

Rhythm, Movement, and the Viewer’s Path

Matisse engineers a precise itinerary for the eye. Entering at the lower edge along the yellow border, the viewer travels left to right, then curves upward along the jug’s handle into the statuette, and finally crosses to the white vase and dark mug. The scattered rosettes in the carpet act as rhythmic markers that keep the eye bouncing within the field rather than escaping to the periphery. The folded ribbon at the bottom sends the gaze back into the composition. This flow is musical: repetition with variation, strong beats provided by the dark vessels, lyrical passages at the statuette and jug where curves prevail.

Comparisons within Matisse’s Oeuvre

Placed alongside Sculpture and Persian Vase of the same year, this canvas feels denser, its space more compressed and its patterning more insistent. Both works stage a conversation between sculpture and ceramic, but Statuette and Vases on Oriental Carpet leans further toward tapestry-like unity, allowing the carpet to subsume almost everything. Compared with the later Red Studio, this painting keeps objects more materially specific; the jug is glass, the vase is ceramic, the statuette is plaster or stone. Yet the seeds of Red Studio are here: the radical tilt, the color field that overwhelms realistic depth, and the conviction that an interior can be built from color blocks, outlines, and a handful of beloved things.

Emotional Tone and Intimacy

Despite its blazing color, the painting radiates calm. The statuette’s poised contrapposto and the jug’s broad shoulders lend dignity. The small vessels and the soft band of fabric bring human scale, as if the painter had just stepped back from arranging them. The Oriental carpet, with its intricate memory of hands and looms, suffuses the scene with a sense of care and craft. The mood is neither hedonistic nor austere; it is attentive. The viewer is invited to linger over edges, compare temperatures, and feel the weight of color as a physical force.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Statuette and Vases on Oriental Carpet remains instructive for artists and viewers because it shows how a limited set of elements can generate extraordinary richness. It demonstrates that pattern can be structural, that color can define space, and that objects become meaningful through their relationships rather than through narrative props. The painting also exemplifies a generous modernism—one that learns from textiles, ceramics, and sculpture; one that embraces non-European ornament not as exotic décor but as a rigorous visual language. In contemporary design and painting, echoes of Matisse’s method are everywhere: tilted planes that flatten space, fields of saturated color interrupted by a few decisive silhouettes, and interiors where objects read as actors on a stage of pattern.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s Statuette and Vases on Oriental Carpet is both intimate studio vignette and sweeping decorative proposition. A red carpet becomes architecture; a handful of vessels and a statuette become characters; and color, contour, and pattern conspire to build a world that is at once shallow and deep, tactile and airy. Painted in 1908, at the threshold of his most influential interiors, the work shows Matisse turning away from naturalistic description and toward a modern plane where form is clarified, space is orchestrated, and the eye moves as if reading music. The painting’s vitality comes from its balances—warm against cool, curve against angle, figure against ground—and from the honesty of its surface, where the hand’s speed and the mind’s order are equally visible. It is a still life that refuses to sit still, a carpet that builds a room, and a demonstration that harmony can be constructed from audacity.