Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

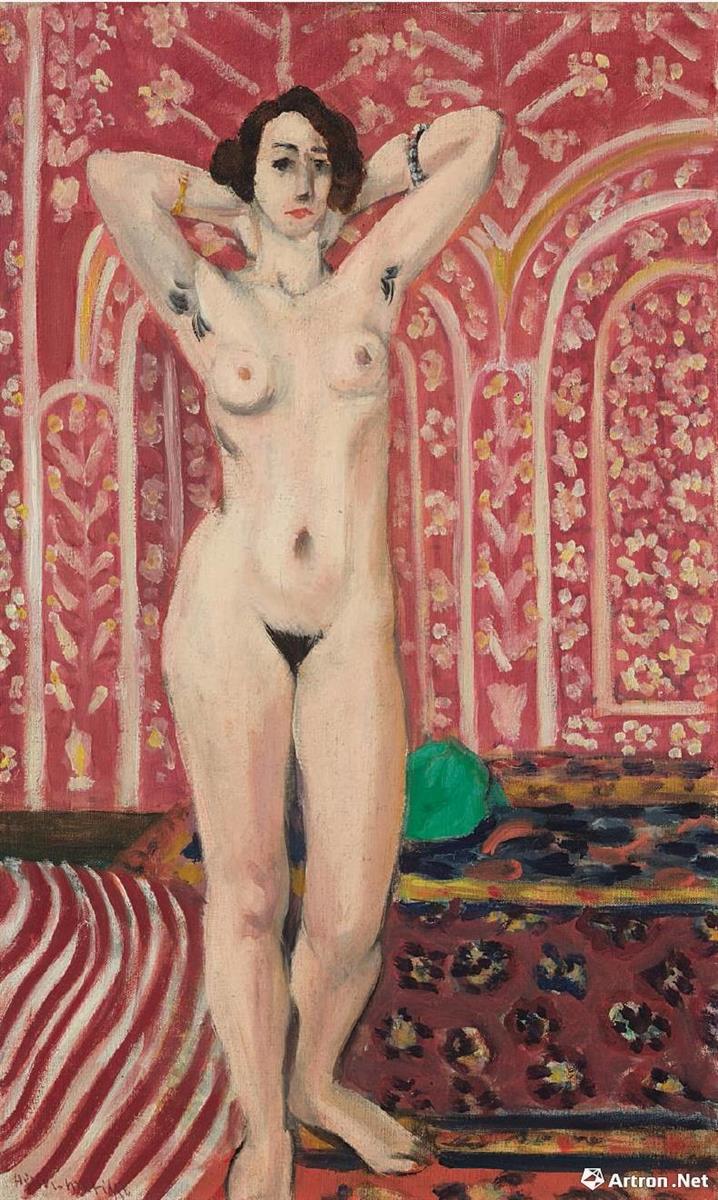

Henri Matisse’s “Standing Odalisque, Nude” (1923) sits at the luminous center of his Nice period, a decade in which the artist repeatedly explored the odalisque motif with an almost musical persistence. The painting presents a standing nude in an interior saturated with pattern and warmth, a moment where flesh, fabric, and ornament merge into a single orchestration of color. What appears, at first glance, to be a simple studio scene becomes, upon closer looking, a sophisticated meditation on how painting can transform space, figure, and desire into pure pictorial rhythm. This canvas distills Matisse’s ambitions after Fauvism: not the shock of bright pigments alone, but the serene, exacting harmony of everything within the frame.

Historical Context and the Odalisque Motif

Matisse had been in Nice intermittently since 1917, drawn by the Mediterranean light and the possibility of working with models in sun-drenched rooms. From the early 1920s onward he painted dozens of odalisques—reclining, seated, or standing women in interiors staged with carpets, screens, and textiles. The odalisque, inherited from nineteenth-century Orientalist painting, offered a culturally charged pretext for depicting the nude, but Matisse reconfigured the trope. Rather than narrate harem fantasies, he built a theater of pattern, where the model becomes a vertical axis around which fabrics, wallpapers, and rugs unfold. The year 1923 marks a moment when his Nice pictures coalesce into a confident language: light is softened, contours are economical, and the arabesque of décor supports rather than distracts from the figure.

Composition and the Architecture of the Pose

The model stands with arms lifted behind her head, the elbows forming a symmetrical crown that echoes the arched tracery of the backdrop. This pose stretches the torso and opens the ribcage, transforming the body into an elegant column. The figure is placed slightly off center, allowing the sweeping curves of the background to press from the right and the diagonal stripes of the left foreground to rise against the body. The placement is not anatomical realism but compositional strategy. Vertical weight is answered by horizontal bands of carpet; delicate arcs in the wallpaper repeat in the curve of hip and shoulder; the dark wedge of pubic hair functions as a visual hinge anchoring the lower half of the canvas. Matisse balances calm with tension—the figure appears relaxed, yet held in place by a lattice of repeated shapes.

Color as Atmosphere and Structure

The dominant color is a saturated pink that floods the wall and infuses the room with warmth. Matisse chooses pink not as decoration but as climate. Against this enveloping field, the figure’s pale flesh reads as an illuminated island, modeled with pearly grays and soft ochres. Small accents control the chromatic temperature: the viridian splash of a cushion or garment near the model’s thigh introduces a cool counterpoint; the deep burgundy and midnight notes in the rug lend ballast to the airy upper field; the lips, barely crimson, keep the face alive without severing it from the tonal unity of the body. Color is not local description but structure—pink scaffolds the space, while the body’s neutrals mediate between intensity and calm.

Pattern, Ornament, and the Logic of Repetition

The painting’s most immediate pleasure is its surface of repeated motifs. The wallpaper’s floral dots and looping arcades recall Moorish screens and painted stucco; the rug below bursts into mottled blossoms; a striped textile on the left rises in a sinuous wave. These patterns are not mere props. They are the grammar that lets the figure speak. Each motif, simplified to a few strokes, establishes a pulse across the canvas. The rhythm of the stripes ascends toward the torso; the rounded arabesques at the right swell behind the elbows; the rug’s spotted forms echo the soft modeling of knees and breasts. Ornament here is a form of thinking. It carries the eye around the painting, calibrating proximity and distance, intimacy and decorum.

Drawing, Contour, and the Economy of Means

Matisse’s line is exquisitely sparing. The contour of the figure appears to hover rather than cut, a graphite-like edge in paint that defines form without imprisoning it. The outlines at the armpits and pubis are darker—as if to admit that certain thresholds require emphasis—while the cheeks, shoulders, and abdomen dissolve gently into the background tone. The hands, hidden behind the head, are implied more than described; the feet, touching patterned ground, are simplified to broad planes that keep attention on the torso’s vertical lift. What matters is the curve’s continuity. The line glides, halts briefly at the hips, and resumes its steady ascent. This control of tempo is the essence of Matisse’s draftsmanship.

Light, Flesh, and the Refusal of Illusion

Unlike academic nudes modeled by rational light sources, this body is illuminated as if from within the painting itself. Shadows take the form of muted violets and cool grays, never brown or heavy. The stomach’s small depression, the sternum’s notch, the slight turn of the thigh—each is indicated with minimal tonal difference, enough to suggest volume without sacrificing the overall flatness. The result is paradoxical: the body feels tactile and inhabited, yet remains an element in a decorative ensemble. By refusing deep illusionistic space, Matisse keeps attention on the painting’s surface, where flesh is paint and paint is rhythm.

Space Without Depth

The room scarcely recedes. The wall, though behind the figure, presses forward as a patterned screen. The carpet does not vanish toward a vanishing point; it becomes a fabric plain, offset by a slender threshold line. This near-flat space, learned from Islamic tiles, Japanese prints, and his own long study of textiles, liberates the composition from the tyranny of perspective. Depth is replaced by layering, like sheets laid on a bed: wall, body, carpet. The viewer senses proximity rather than distance, intimacy rather than stage illusion. This spatial compression intensifies the encounter with the model and heightens the sensation of color as something we breathe as much as see.

The Model, the Gaze, and the Fiction of the Harem

The model stands with an unflustered self-possession, looking outward with an expression that is neither coy nor confrontational. Matisse’s odalisques are sometimes criticized as projections of Orientalist fantasy. It is true that the décor borrows freely from North African and Middle Eastern visual vocabularies, and the term “odalisque” carries a long history in European art. Yet in this work the erotic is sublimated into formal clarity. The woman is neither narrative character nor ethnographic type; she is a presence calibrated to the painting’s internal music. Her gaze meets ours at the level of the picture plane, flattening the power dynamics of viewing by placing us in the same decorative world she inhabits.

Materials, Brushwork, and the Slowness of Making

Although the surface reads as effortless, signs of deliberation abound. The wallpaper’s motifs vary in density, suggesting passages reworked and restated. The rug’s floral marks are dabbed, dragged, and tamped into the weave of the canvas. On the figure, broader, creamier strokes alternate with thin scumbles that let underlayers breathe through. The economy of paint is deceptive; Matisse often labored through many sessions to reach this state of apparent simplicity. The visible brushwork is not bravura but editing. Every stroke that remains has been tested against the painting’s balance of shape and interval.

Dialogue with Tradition

“Standing Odalisque, Nude” converses with a centuries-long lineage of nudes, from Titian’s Venuses to Ingres’s sleek bodies. Matisse admired Ingres’s contour, yet he breaks from the linear chill of neoclassicism by submerging the figure in sensual color. He also responds to Manet’s insistence on the picture surface, keeping the painting’s frankness alive without Manet’s scandal. Equally important is the lesson of Islamic ornament and North African interiors, which Matisse studied during travels in Morocco. The painting’s patterns do not imitate any specific source; instead they distill a larger understanding of how geometry and floral motifs can construct space without perspective.

Comparisons Within the Nice Period

When compared to the reclining odalisques of 1924 or the richly accoutered scenes with musical instruments and embroidered jackets, this standing version is austere. The accessories are reduced to textiles and a single green object, perhaps a satin cap or folded garment. The pose, upright and frontal, turns the model into an architectural element, akin to a caryatid supporting an invisible entablature. This minimalism clarifies what mattered most to Matisse in 1923: the consonance of body and décor, achieved by stripping away narrative distractions and letting color-pattern relations carry the image.

Emotion, Sensuality, and the Ethics of Pleasure

Matisse famously spoke of art as an armchair for the tired businessman, a line often misread as a retreat into comfort. In this painting, pleasure is neither frivolous nor complacent; it is a measure of clarity. The odalisque’s calm posture, the diffused warmth of the room, the slow repetition of motifs—together they generate an emotional tone closer to contemplation than titillation. Sensuality appears not as spectacle but as equilibrium, a bodily feeling of being at home within color and form. The work proposes an ethics of pleasure grounded in attention, softness, and respect for the body as a living rhythm.

The Role of the Decorative

Calling Matisse “decorative” once served as a dismissal. Here, decoration is the very engine of modernity. The term should be understood in its root sense: to arrange, to adorn, to order. The decorative in this painting does not trivialize the figure; it democratizes the visual field. Flesh is no longer privileged by sculptural modeling while backgrounds recede into anonymity. Instead, everything participates in the same order of value. The rug’s pattern, the wall’s arabesques, and the body’s contours share a single pictorial dignity. This leveling of hierarchies, far from superficial, becomes a radical statement about what painting can be.

Time, Stillness, and the Studio as Stage

The painting’s time is unusually slow. The lifted arms imply a stretch held long enough for the artist to draw; the vacant interior suggests a studio emptied of all but essentials; the lack of external reference—no window, clock, or narrative action—suspends the moment. Matisse constructs a stage where time is measured in brushstrokes. The viewer’s eye loops through repeating motifs like a metronome. This stillness was hard won. After the disruptions of the First World War, the Nice pictures seek stability without rigidity, serenity without inertia. “Standing Odalisque, Nude” exemplifies that aspiration.

Body Politics and Modern Beauty

The figure’s proportions resist both classical ideal and pin-up fantasy. The belly is softly rounded; the thighs carry weight; the shoulders are strong; the pubic triangle is indicated bluntly. Matisse insists on a beauty grounded in presence rather than perfection. By treating the body as a harmonic instrument within an ornamental field, he offers an alternative to the objectifying gaze. The painting does not ask the viewer to appraise the model’s physique; it invites us to appreciate the eloquence of her stance and the fineness of the pictorial balance that surrounds her.

Technical Coherence and the Unity of the Canvas

One of the painting’s quiet triumphs is its unity. No passage feels foreign to another. The pink behind the figure supplies a faint undertone to the flesh; the rug’s darker reds and blues prevent the composition from floating away; the green accent is tiny but crucial, a complementary check that keeps the pink from becoming sugary. Edges fluctuate from crisp to porous at just the right moments. The vertical of the figure meets the horizontals of the carpet with a gentle interlock rather than a hard seam. The entire surface behaves like a woven textile in which colors and forms interlace.

Reception and Legacy

Matisse’s odalisques were championed by collectors and criticized by some contemporaries who saw in them a retreat from the experimental edge of the prewar avant-garde. Yet history has revealed their structural daring. Painters from Léger to Diebenkorn, from the Pattern and Decoration movement to contemporary artists investigating the body within ornament, have drawn lessons from this period. The fusion of figure and décor in “Standing Odalisque, Nude” laid groundwork for later conversations about flatness, the politics of the gaze, and cross-cultural visual vocabularies. Its legacy lies not only in its beauty but in the way it reframed what a figure painting could do.

How to Look at the Painting Today

To approach this work now is to practice attentive seeing. Begin by letting your eyes acclimate to the pink atmosphere. Notice how quickly your gaze returns to the vertical of the body, then slides along the elbows to the arches behind. Trace the stripes at left as they lift you back toward the torso. Observe how little paint is required to suggest the collarbone’s bend or the knee’s volume. Consider the way the model’s steady gaze tempers the decorative exuberance, keeping the scene intimate rather than theatrical. The more slowly you look, the more the painting reveals its architecture of echoes.

Conclusion

“Standing Odalisque, Nude” distills Matisse’s Nice period into a poised, radiant whole. It is a painting about equilibrium—between body and pattern, line and color, presence and décor. The odalisque is no longer a mythic figure from a distant harem but a modern image of stillness within abundance, a person set among harmonies rather than in a story. In 1923, Matisse had the confidence to let color carry meaning and to trust that a few well-placed lines could hold an entire world together. The result is an enduring lesson in how painting turns sensual experience into disciplined grace.