Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

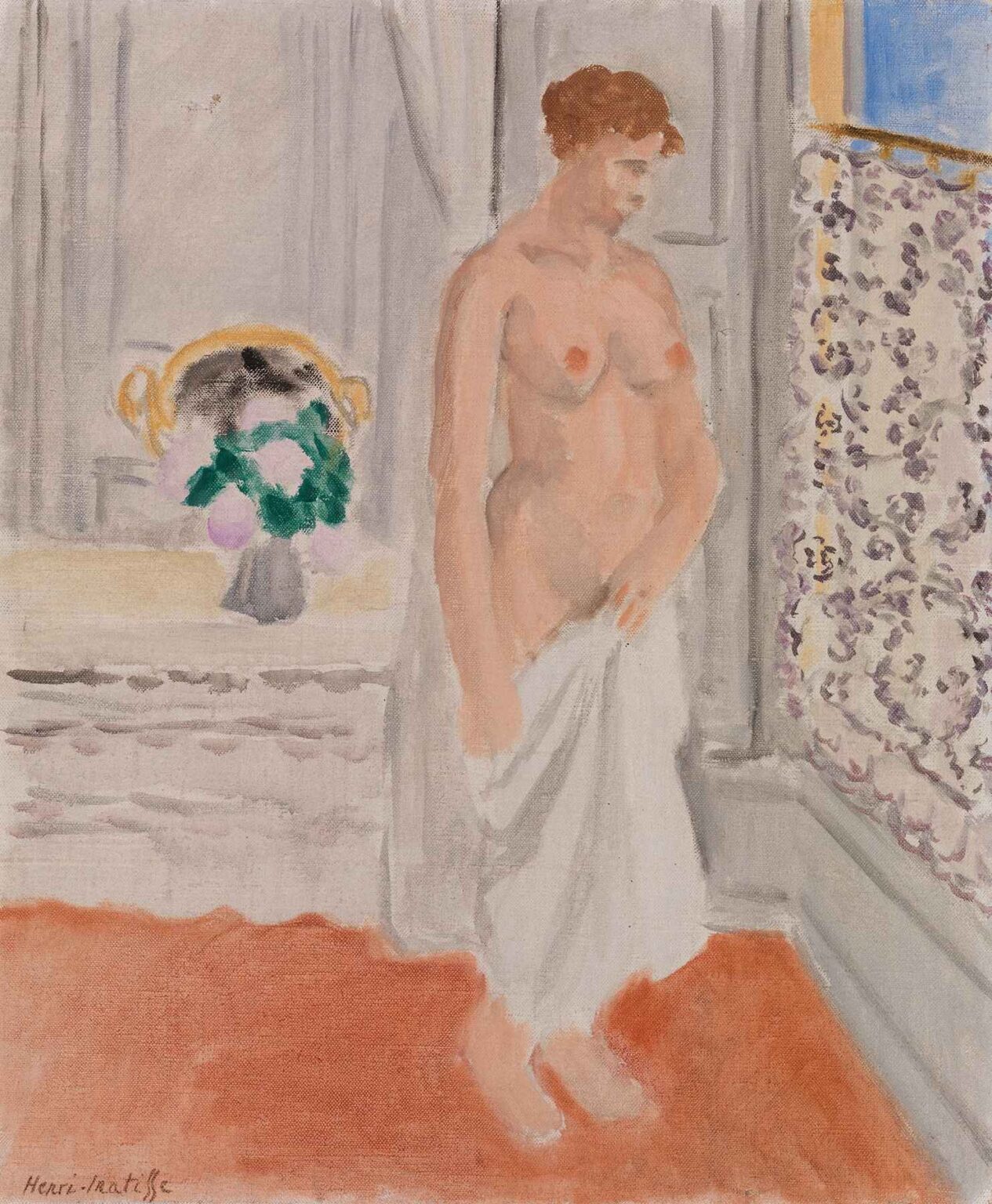

Henri Matisse’s Standing Nude near Window (c. 1918–1920) represents a crucial moment in the artist’s evolution from Fauvist audacity toward a more contemplative, decorative modernism. Painted in the aftermath of World War I, the work reflects Matisse’s belief that art could provide a sanctuary of beauty and calm amid societal upheaval. In this large‐scale canvas, a solitary nude woman stands before partly opened shutters, bathed in soft Mediterranean light and surrounded by patterned drapery and a glimpse of the Mediterranean beyond. Far from a sensual display, the figure becomes an integral element in a symphony of color, pattern, and light. Over the course of this analysis—spanning historical context, compositional construction, chromatic strategies, spatial design, brushwork technique, psychological resonance, thematic undercurrents, and placement within Matisse’s broader oeuvre—we will see how Standing Nude near Window epitomizes the artist’s pursuit of harmony between figure and environment.

Historical Context and Biographical Background

When Henri Matisse returned to France after his service as a Red Cross orderly, he sought refuge on the southern Mediterranean coast, where the intensity of light and the simplicity of daily life offered relief from the war’s trauma. By the late 1910s, he had shifted from the wild, arbitrary colors of his early Fauvist period toward subtler, more integrated harmonies, yet he remained committed to color as an expressive force. Nice, with its vivid sky and shutters framing sea vistas, became a recurring motif in his interiors and nudes. The precise dating of Standing Nude near Window remains debated among scholars, but the painting’s whitened walls, shuttered window, and patterned curtain echo interiors he explored around 1918–1920. Painting this canvas during a time of personal and collective recovery, Matisse was intent on reasserting the restorative power of beauty: the nude stands as a symbol of rebirth and purity, while the window serves as both literal and figurative aperture to a world of light and renewal.

Compositional Framework

At the heart of Standing Nude near Window lies a masterful balance between vertical and horizontal forces. The painting is organized by the tall, upright posture of the nude figure, whose head nearly touches the top of the canvas. Her elongated form forms the central vertical axis, flanked on the right by the shuttered window and on the left by a vase of flowers perched atop a mantel or console. The lower third of the canvas is dominated by the warm, terra‐cotta floor, which extends from foreground to the base of the shutters. This broad horizontal band provides stability, grounding the figure and counterbalancing the upward thrust of her body and the window panels. Between the floor and the upper registers, the swath of patterned drapery introduces a diagonal element: it sweeps from the right toward the figure’s midsection, subtly guiding the viewer’s eye back into the pictorial center. Rather than employing strict linear perspective, Matisse layers these compositional elements—floor, figure, curtain, shutters, and sky—into shallow planes that overlap gently, creating a tapestry of interlocking shapes.

Color as Structure and Emotion

Color in Standing Nude near Window serves both to articulate form and to evoke an emotional atmosphere of calm introspection. Matisse’s palette here is more restrained than in his earliest Fauvist works, yet no less powerful in its effect. The nude’s flesh is rendered in a range of pale pinks, warm creams, and faintly cool grays, the subtle modulation of which suggests the gentle caress of daylight through the shutters. Against this delicate portraiture stands the boldly saturated terra‐cotta of the floor—a warm, earthen counterpoint that resonates with the skin tones and provides a sense of rootedness. The shutters themselves are painted in a pale dove gray, their vertical slats relieved only by a hint of cobalt sky shining through the slightly opened panels. This cool blue contrasts with the floor’s warmth and echoing skin tones, creating a dynamic yet restful chromatic balance. The patterned curtain—its lavender and violet arabesques on ivory ground—repeats the notion of blue‐gray and flesh‐tones harmony, binding together figure and setting into a coherent color scheme. Through these calibrated contrasts and resonances, Matisse elevates color beyond descriptive function; it becomes the very architecture of emotion, infusing the scene with serenity and introspective poise.

Treatment of Light and Shadow

Instead of relying on dramatic chiaroscuro, Matisse suggests illumination through adjacent shifts in hue and value. The nude’s body is subtly modeled: planes facing the shutters carry cooler pale grays, while surfaces turned away receive warmer peach or rose. Shadows beneath the chin, at the ribcage, and in the fold of the towel drape emerge not from deep black but from slightly darker, cooler tones that recede without harshness. The shutters’ pale gray panels are brushed lightly to hint at hidden structure but remain luminous, reflecting ambient exterior light. Above, glimpses of cerulean sky are painted with swift, horizontal strokes, implying transient clouds and the possibility of open air beyond the closed interior. The mantel’s vase of flowers—its petals in pale purple and leaves in bright emerald—carries highlights that further attest to a diffused daylight gently washing across the scene. In Matisse’s hands, light becomes a soft, enveloping presence, a quiet partner to the painting’s decorative harmony.

Spatial Design and Flattening

Although the painting depicts a three‐dimensional interior, Matisse purposefully flattens the space, inviting viewers to engage with pattern and color on the canvas surface rather than peer into an illusionistic room. The floor is indicated by a single broad band of terra‐cotta without receding perspective lines. The patterned curtain overlaps both floor and figure, yet it reads equally as a decorative panel. The shutters, though rendered with vertical slats, lack a vanishing point and instead function as an elegant geometric backdrop. Overlapping is minimal and restrained: the nude’s foot overlaps the floor strip, the edge of the towel overlaps her thigh, and the curtain overlaps the window frame. Shadows are nearly absent, save for faint greys in recessed corners. In this shallow pictorial field, each element—nude, towel, curtain, shutters, vase—occupies its own decorative zone, yet they interlock through color, line, and brushwork to form a unified surface. This approach underscores Matisse’s credo of painting as ornament, where the canvas reads as a tapestry of motifs rather than a mere window onto reality.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Matisse’s brushwork in Standing Nude near Window demonstrates both confidence and sensitivity. Large areas—the shutters, the floor—are painted in even, broad strokes that leave the weave of the canvas perceptible, lending a sense of luminosity. The figure’s flesh is modeled with thinner, more blended strokes that suggest the smoothness of skin without obliterating the painterly gesture. The towel drape and the curtain pattern emerge from more flickered, sinuous marks: here the bristles have left visible ridges of pigment, imparting a tactile quality that contrasts with the flat ground. The vase of flowers on the mantel is sketched in swift, lively touches—leaves indicated by quick flicks of emerald, petals by dabs of lavender—adding a spontaneous accent to the otherwise measured composition. Throughout, Matisse retains evidence of the artist’s hand: each stroke contributes to the decorative whole while bearing the vitality of individual gesture.

Psychological Presence and Emotional Tone

Although the nude’s face is turned slightly downward and away from the viewer, her posture and placement convey a sense of quiet dignity and introspection. She stands neither rigid nor languid, but in a poised state of equilibrium—shoulders relaxed, head inclined in contemplation. The towel held at her hip suggests modesty, yet the openness of the scene, with light pouring through the shutters, precludes any sense of voyeuristic intrusion. The patterned curtain, drawn partially aside, becomes a screen through which she both reveals and conceals herself, embodying the interplay of public and private. The quiet atmosphere of the interior—absent other figures or narrative drama—invites viewers into a space of personal reflection, echoing Matisse’s belief in painting as a means of spiritual replenishment.

Thematic Underpinnings

On one level, Standing Nude near Window continues the tradition of the female nude in Western art, yet Matisse transforms the archetype through his decorative modernism. The painting moves beyond pure eroticism or classical ideal—common in academic nudes—toward a domestic poetics in which the nude becomes part of a beautifully orchestrated environment. Themes of modesty, introspection, and harmony between human and setting emerge through the interplay of figure, towel, and decorative elements. The half-open shutters evoke notions of threshold and revelation, as if the model stands on the brink between interior privacy and exterior freedom. The pattern of the curtain, reminiscent of wallpaper or textile design, suggests the permeability of boundaries—public and private, inside and out. In this sense, the painting becomes a meditation on the thresholds of consciousness, inviting us to consider how environment, light, and form shape our inner states.

Place in Matisse’s Oeuvre

Executed during Matisse’s decorative phase, Standing Nude near Window follows canvases such as The Venetian Blinds (1919) and Interior with Two Figures, Open Window (1922) in its flattened space, patterned backdrop, and harmonious palette. Yet it predates the cut-paper “gouaches découpées” of the 1940s, foreshadowing Matisse’s eventual distillation of form and color into pure, flat shapes. Compared with his Fauvist nudes of 1905–1906—marked by explosively arbitrary color—this work demonstrates a matured restraint: color remains central but is deployed with greater subtlety alongside a refined sense of pattern and light. Within the arc of his career, the painting stands as a bridge between raw chromatic experimentation and the later abstractions in which figure and decoration become inseparable.

Influence and Legacy

Matisse’s Standing Nude near Window has resonated with subsequent generations of artists exploring the intersection of figure and environment. Abstract Expressionists took inspiration from his bold flattening of space and emphasis on surface gesture, while designers have drawn on his color harmonies for textiles and interiors. Contemporary figurative painters continue to reference his interiors when seeking to convey psychological nuance through pattern and light. The painting’s enduring appeal lies in its demonstration that beauty emerges from the integration of figure, setting, and paint itself—a lesson that transcends stylistic trends.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s Standing Nude near Window transcends its simple subject to become a radiant exploration of color, pattern, and human presence. Through its refined composition, harmonious yet evocative palette, flattened space, and expressive brushwork, the painting offers a vision of the nude as part of a living decorative tapestry. Created during a moment of personal and collective recovery, it asserts art’s power to transform interior spaces into realms of beauty and introspection. Over a century later, Standing Nude near Window continues to captivate, reminding us that within the quiet interplay of figure and setting lies the possibility of profound aesthetic and emotional resonance.