Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

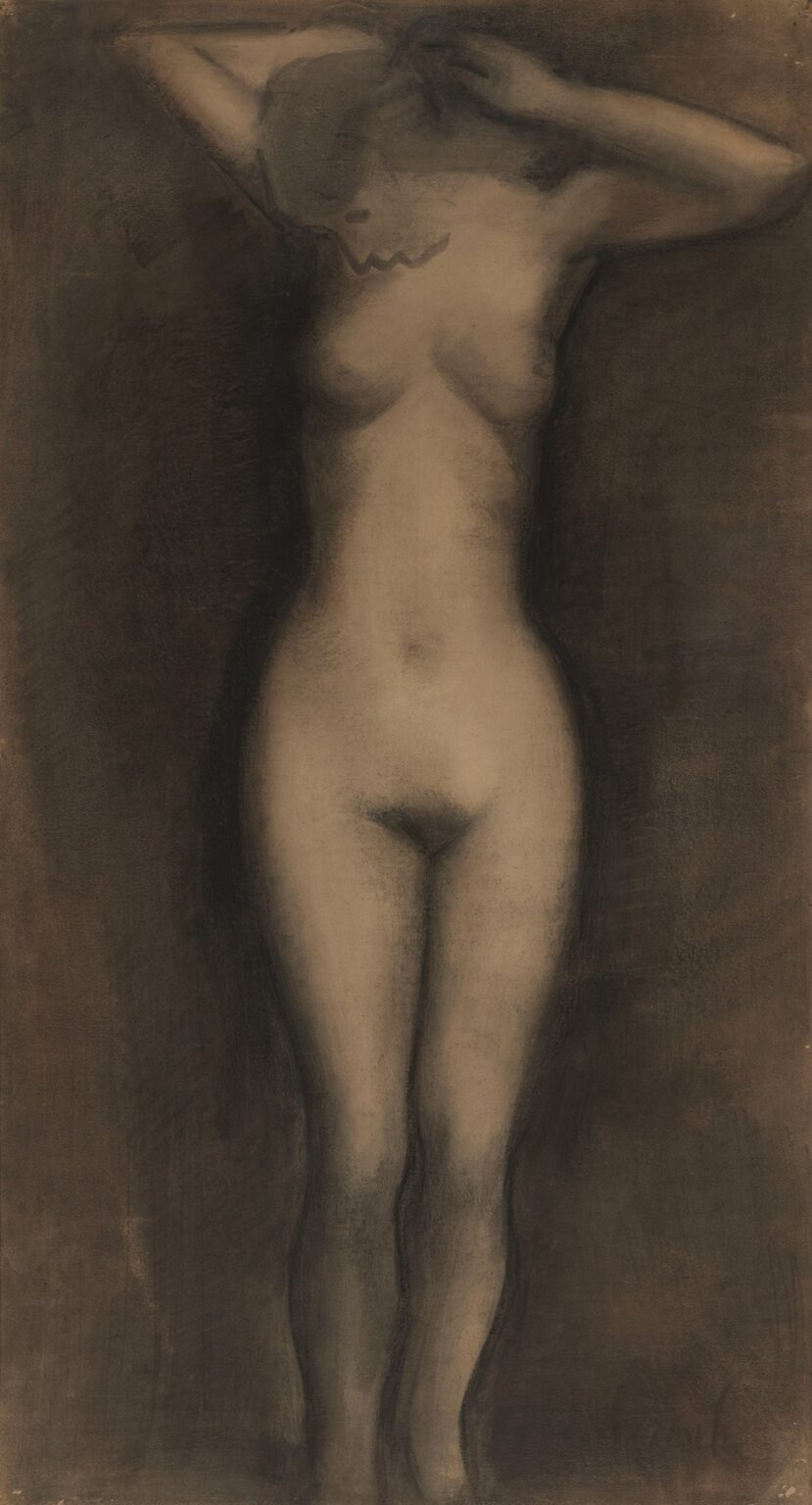

Constant Permeke’s “Standing Nude” (1946) stands as a defining testament to the artist’s late-career exploration of the human form in its most elemental state. Painted in the immediate aftermath of World War II, this work forgoes narrative details and extraneous symbolism in favor of a singular focus: the quiet dignity of a solitary nude figure. The subject, rendered in muted umber and ochre tones, emerges from a deep, shadowed background with an almost sculptural presence. Arms gracefully lifted behind her head, she invites viewers into an intimate dialogue on vulnerability, resilience, and the enduring power of flesh and pigment. In the following analysis, we will examine the historical backdrop that shaped the painting, trace Permeke’s evolution toward this distilled style, and unpack the formal, chromatic, and psychological dimensions that render “Standing Nude” a masterpiece of post-war figuration.

Historical Context

Europe in 1946 was marked by the trauma of recent conflict and the demanding task of social and physical reconstruction. Belgium—Permeke’s homeland—had endured occupation, liberation, and the moral reckoning of collaboration and resistance. In the arts, many practitioners sought new visual languages to articulate collective suffering: some embraced abstraction, others turned to coded symbolism or surrealist imagery. Permeke charted a different course. Rather than retreat into nonrepresentational modes or overt political critique, he rediscovered the human body as the primary site of existential inquiry. “Standing Nude” emerges from this milieu as both a personal and universal statement. The artist’s choice to depict an unidealized, solitary nude underscores a collective desire to reclaim humanity’s core dignity after years of dehumanization. In the absence of clothing, background props, or explicit narrative, the figure becomes a silent manifesto: vulnerable yet unbowed, at once exposed and empowered.

Permeke’s Artistic Evolution

Born in 1886 in Antwerp and raised on a farm in Ostend, Constant Permeke forged his early career amid the elemental forces of sea and soil. His formative exposure to rural labor informed his signature Expressionist canvases of fishermen and peasants, painted with thick impasto and bold, simplified forms. During the interwar decades, Permeke’s palette darkened and his compositions grew more introspective, as economic hardship and rising political tensions prompted artists across Europe to examine inner landscapes. The devastation of World War II deepened his inward turn: large-scale communal tableaux gave way to solitary figural studies, often on paper, where the nude form replaced maritime scenes. By 1946, “Standing Nude” exemplifies this mature phase. The robust energy of his earlier works is reined in, yielding to a solemn meditation on the body itself as both subject and symbol.

Formal Composition

At the heart of “Standing Nude” lies a rigorously balanced composition, achieved through the interplay of vertical and diagonal axes. The figure’s spine aligns with the canvas’s central vertical, granting her an unshakable presence. Subtle shifts—such as the tilt of the hips and the outstretched right leg—introduce gentle diagonals that animate the pose without breaking its stately calm. The arms, lifted behind the head in a broad sweep, form a shallow arch that echoes the curve of the torso below. This rhythmic counterpoint of curves and straight lines guides the viewer’s gaze from the headless shoulders down to the graceful taper of the legs. The background remains deliberately abstract—deep swaths of shadow envelop the form, while narrow bands of lighter pigment around the edges suggest an indeterminate space. By isolating the nude within this abstract field, Permeke directs focus entirely onto the sculptural interplay of mass and void that defines the human body.

Color Palette and Light

Permeke’s restrained palette in “Standing Nude” draws from the earthy tones of his Flemish roots. Umber, sienna, and muted ochre provide the foundational hues, layered in translucent washes that allow the canvas texture to permeate the flesh. Highlights—applied sparingly along the collarbones, the swell of the breasts, and the hips—emerge in pale ochre, as though the body emanates its own gentle glow. Shadows deepen to near-black around the arms and torso’s recesses, sculpting volume through tonal gradations rather than hard outlines. Light in this painting is diffuse, lacking a single directional source; instead, it appears to diffuse inward, as if the figure itself is a beacon of quiet luminosity. This subtle modulation of color and light reinforces the painting’s contemplative mood and underscores the notion that presence—not drama—is central to the work’s emotional impact.

Brushwork and Texture

A defining feature of Permeke’s late style is his tactile brushwork, and “Standing Nude” exemplifies this approach. The background is built with broad, horizontal scumbles, each stroke varying in thickness and opacity to create a richly textured field that pulses beneath the figure. On the nude form, the application shifts: long, confident strokes trace the contour of the torso, while softer, feathered touches model the planes of muscle. In certain areas—around the waist and thighs—Permeke lifts paint with a knife or brush handle, revealing underlayers that glimmer like weathered plaster. The interplay of dense impasto and thin glaze, abrupt scrape and smooth blend, transforms the painting into an object of palpable materiality. Viewers are made aware of both the subject and the medium, as each mark testifies to the artist’s physical engagement with the canvas.

Anatomical Realism and Abstract Simplification

Although grounded in anatomical truth, Permeke’s nude is far from academic. He selectively simplifies forms to emphasize mass, rhythm, and emotional resonance. The ribcage is suggested rather than delineated; the breasts bear their natural weight without idealization; the waist narrows in a gentle S-curve that conveys both grace and strength. The slight asymmetry of the hips and the tilt of the shoulders lend authenticity, while the headless presentation abstracts identity, transforming the figure into an archetype of human vulnerability and resilience. By paring away individualizing details, Permeke invites viewers to project their own emotions and experiences onto the form, rendering the nude simultaneously specific and universal.

Psychological Resonance

Despite—or indeed because of—its formal restraint, “Standing Nude” resonates with profound psychological depth. The figure’s posture, with arms raised overhead, evokes both openness and self-protection, as if she sheltering an inner core of feeling. The downward tilt of the torso and the subtle curve of the spine suggest introspection, while the absence of facial features leaves her emotional state suspended in shadow, an invitation for viewers to inhabit her silence. In post-war Europe, such a silent pose would have mirrored collective longing for rest, reflection, and healing. Permeke’s nude thus becomes a site of empathetic projection, allowing each observer to encounter their own vulnerability and hope in the delicate balance of exposure and concealment.

The Nude in Post-War Art

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the nude emerged in European art as a charged emblem of human fragility and renewal. Some artists embraced abstraction to articulate inexpressible trauma, while others turned to the body as a refuge of authenticity. Permeke’s “Standing Nude” aligns with the latter impulse, affirming the nude form’s capacity to convey universal emotional truths without recourse to narrative or allegory. By eschewing classical idealization and refusing to objectify his model, Permeke positions the nude as an equal partner in dialogue—the body as subject rather than spectacle. This humanist approach contrasts with both the objectifying tendencies of academic tradition and the depersonalizing extremes of some avant-garde movements.

Comparison to Permeke’s Earlier Works

When set beside Permeke’s seminal 1920s canvases of fishermen at sea, “Standing Nude” appears almost austere by comparison. Early works pulsated with collective energy, bold outlines, and vivid pigment, while the 1946 nude is spare, tactile, and introspective. Yet traces of his foundational vision endure: the monumental treatment of form, the earthy palette, and the emphasis on the body as a vessel of elemental truth. The evolution from communal maritime scenes to solitary nudes reflects Permeke’s shifting focus from external labor to internal experience. In this light, “Standing Nude” serves as both a culmination of his lifelong engagement with the human body and a harbinger of his final explorations into figural abstraction.

Conservation and Legacy

Since its debut in Belgian exhibitions shortly after its completion, “Standing Nude” has been recognized as a cornerstone of Permeke’s late corpus. Conservators note the painting’s remarkable stability: the interplay of thick impasto and thin glaze has resisted cracking, while the scraped surfaces retain their vivid texture. Environmental controls ensure the painting’s longevity, particularly in preserving the delicate nuance of the shadowed edges. Art historians frequently cite “Standing Nude” as emblematic of humanist figuration in post-war Europe, a bulwark against the growing dominance of abstract expressionism. Its influence can be traced in the work of later artists who sought to balance formal reduction with emotional richness, affirming Permeke’s legacy as a pivotal bridge between Expressionist vigor and existential realism.

Conclusion

Constant Permeke’s “Standing Nude” (1946) remains a masterful exploration of the body’s dual capacity for vulnerability and resilience. Through a disciplined composition, muted earth-tone palette, and layered, textured brushwork, Permeke transforms a solitary nude into a universal meditation on post-war renewal and the sanctity of flesh. The figure’s poised yet introspective pose, headless anonymity, and sculptural modeling invite viewers into a silent dialogue about suffering, survival, and the enduring dignity of the human form. Situated at the crossroads of Flemish Expressionism and mid-century modernism, “Standing Nude” endures as a profound testament to art’s ability to reclaim humanity in times of profound upheaval.