Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

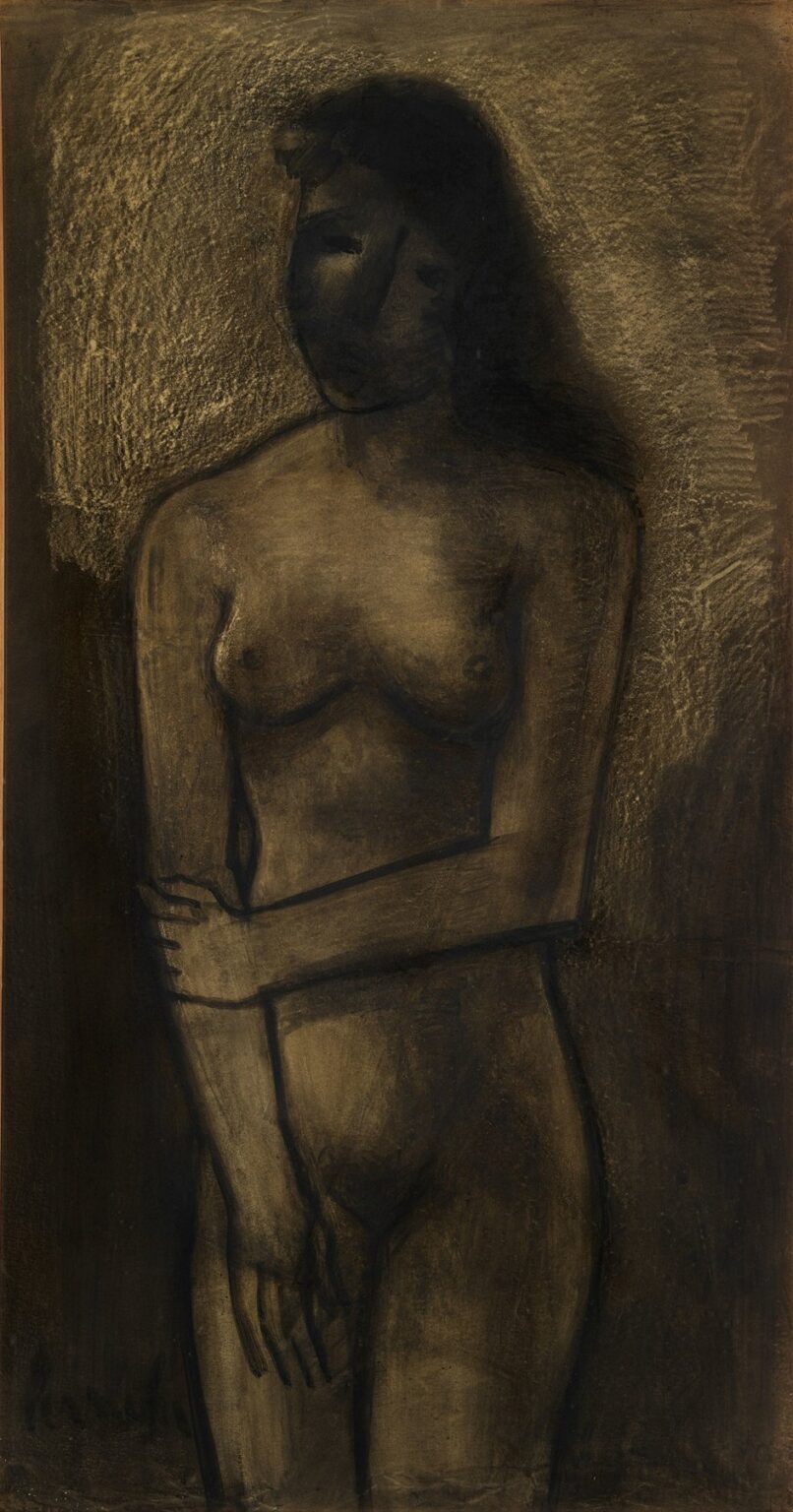

Constant Permeke’s “Standing Naked” (1946) commands attention through its austere presentation of the human form and its profound emotional undercurrents. Rendered in muted earth tones and sculpted through layered washes of paint, the standing nude emerges from a shadowed, nearly abstract background. Her posture—vertical yet slightly inclined, with arms crossing the torso—suggests both vulnerability and quiet self-possession. Created just after the end of World War II, this painting reflects Permeke’s ongoing quest to find solace and affirmation in the elemental reality of the body. In the absence of narrative context or decorative excess, the figure itself becomes the focal point of existential reflection. This analysis will unfold through a series of thematic examinations—historical context, artistic evolution, formal composition, color and light, brushwork and texture, anatomical and gestural expression, psychological resonance, and the painting’s place within Permeke’s oeuvre—revealing how “Standing Naked” stands as a masterful testament to resilience and human dignity.

Historical Context

Europe in 1946 grappled with the aftermath of unprecedented destruction. Belgium, Permeke’s homeland, bore the scars of occupation and liberation, its social fabric frayed by loss and displacement. Cultural life struggled to resume normalcy as artists confronted both personal and collective trauma. Many turned to abstraction as a means of articulating the ineffable horrors of war, while others employed symbolic imagery to critique totalitarianism. Permeke charted a different course: he returned to the human figure in its most unadorned state, positing the nude body as a bearer of universal truth. In “Standing Naked,” the absence of external references—no landscape, no architectural cues—underscores a world stripped to essentials. The painting’s somber palette and the figure’s introspective stance evoke a moment of quiet reckoning, when individuals sought inner resources to heal and rebuild. Through this lens, the standing nude becomes both a personal manifesto and a collective meditation on survival.

Permeke’s Artistic Trajectory up to 1946

Constant Permeke (1886–1952) began his career immersed in the elemental grandeur of Flemish rural life. His early works—vibrant canvases of fishermen laboring at sea and peasants tending fields—celebrated communal resilience and the dignity of manual work. Thick impasto and simplified, monumental forms characterized his Expressionist vocabulary. The interwar years saw Permeke refining his palette into deeper, more introspective tones, and his subject matter increasingly focused on solitary figures. World War II’s upheavals prompted him to pare back further, channeling his expressive energy into nude studies. By 1946, Permeke had achieved a mature style defined by austere compositions, sculptural modeling, and tactile surfaces. “Standing Naked” embodies this evolution: the communal drama of his youth gives way to an intimate encounter with the individual body as a site of existential inquiry, while the painterly gestures of his mid-career persist in the textured handling of paint.

Formal Composition

The composition of “Standing Naked” is a masterclass in visual economy. The figure occupies the central vertical axis, her stance erect and unyielding, yet the slight tilt of her hips introduces a gentle counter-diagonal that enlivens the pose. Her arms cross lightly at the waist—one hand resting on the opposite forearm—creating an X-shaped rhythm that guides the viewer’s eye back to the torso and face. Negative space envelops her in shadowed passages of umber and sienna, forming an indeterminate backdrop that neither suggests a room nor a landscape. This absence of setting intensifies the viewer’s focus on the nude form as sole subject. The vertical of the body and the horizontal suggestion of shoulders establish a stable grid, while the diagonal gestures introduce dynamic tension. In this tightly composed framework, every glance returns to the interplay of form and void, underscoring the painting’s meditative stillness.

Color Palette and Light

Permeke’s palette for “Standing Naked” draws from the earth itself: deep umbers, muted ochres, and warm siennas interweave to model flesh and shadow. The background employs broader, diluted washes of pigment, allowing the canvas weave to emerge in places and lending the scene a worn, tactile quality. The figure’s skin is built through layered glazes of ochre and buff, permitting subtle tonal gradations to define muscle and bone. Highlights—applied sparingly along the collarbones, the swell of the breasts, and the high points of the thighs—suggest an ambient, diffused light that seems to emanate from within the painting rather than from an external source. Shadows deepen through successive applications of darker pigment, softening around the arms and hips to convey volume without harsh contrasts. This restrained chromatic harmony reinforces the portrait’s introspective mood, as if light and color themselves are engaged in a quiet dialogue about presence and absence.

Brushwork and Texture

A defining characteristic of Permeke’s late style is his tactile engagement with paint, and “Standing Naked” exemplifies this approach. In the background, broad, horizontal strokes create a varied tapestry of color, punctuated by areas where pigment has been scumbled or lifted to expose the raw canvas. On the figure, brushwork becomes more purposeful: long, curved marks trace the contours of the legs, soft feathering delineates the torso, and decisive strokes define the arms. In places—particularly around the collarbone and upper thigh—Permeke scraped paint to reveal underlayers, adding depth and temporal resonance. The combination of thick and thin passages, smooth blends and visible brush ridges, invites viewers to sense the painting as an object of material presence. Through these layered gestures, Permeke underscores the physical labor of painting, mirroring the body’s own layered history of experience and survival.

Anatomical Realism and Gesture

While Permeke adheres to believable human proportions, he allows himself expressive license to emphasize character. The figure’s hips are softly rounded, the breasts modeled with natural weight, and the torso elongated to convey both grace and vulnerability. The crossing of the arms at a low point on the torso signals an instinctive gesture of protection, mirroring the universal human desire to guard the self. The slight bend of one knee and the weight shift onto the opposite leg introduce a subtle sense of movement within stillness. Subtle asymmetries—the gentle depression at one waist side, the uneven spacing of the collarbones—lend realism and avoid lifeless perfection. These anatomical nuances serve not merely to capture form but to animate it with emotional truth, allowing the nude to function as both an individual portrait and an archetype of human vulnerability and resilience.

Psychological Resonance

Despite its formal restraint, “Standing Naked” communicates a powerful psychological presence. The figure’s face, rendered with minimal detail, gazes outward yet seems inwardly focused, as if caught between self-awareness and contemplation. Her downcast eyes and the subdued set of her mouth evoke a mood of introspection, perhaps tinged with melancholy or guarded optimism. The interplay of light and shadow across her features and torso reinforces this sense of inner duality—part of her lies open to the viewer, part remains concealed in darkness. In a post-war context where individuals had endured trauma and displacement, this portrait resonates as a mirror for collective emotions: the tension between the desire for openness and the need for self-protection. Permeke’s nude thus becomes an empathetic bridge, inviting viewers to share in her moment of silent reflection.

Position within Permeke’s Oeuvre

“Standing Naked” occupies a pivotal place in the arc of Permeke’s career. While his early and mid-career works celebrated communal narratives of labor and struggle, his late work turned toward solitary figures to explore existential themes. Compared to his more monumental wartime nudes—where verticality and ritualistic poses underscored broader spiritual concerns—this 1946 study is notable for its intimate scale and its paring down of detail. Yet it retains the essential qualities that define Permeke’s mature style: sculptural modeling, tactile surfaces, and a palette of muted earth tones. Situated between his wartime nudes and his post-war portraits, “Standing Naked” bridges the personal and the universal, underscoring his conviction that the human body itself is the ultimate repository of emotional and spiritual truth.

Cultural Significance of the Nude After World War II

In the aftermath of World War II, the nude emerged as a potent symbol in European art. Some artists pursued abstraction to grapple with collective trauma, while others turned to the body to reaffirm human agency and dignity. “Standing Naked” participates in this latter tendency, offering the nude not as an object of erotic display but as a site of quiet resistance to dehumanization. By emphasizing naturalistic form over idealization, Permeke’s nude underscores the inherent value of every individual body, regardless of social context. In this sense, the painting functions as both personal testimony and universal manifesto: it proclaims that even when stripped bare of possessions, identity, and security, the human form remains a resilient vessel of experience and hope.

Conservation and Reception

Since its completion in 1946, “Standing Naked” has been celebrated in Belgian exhibitions and acquired by institutions dedicated to twentieth-century Flemish art. Conservators note the painting’s stability, with Permeke’s layered oil technique retaining both surface texture and tonal subtlety over decades. Careful environmental controls ensure that the scraped and scumbled areas—where pigment layers are thin—remain intact. Art historians frequently cite “Standing Naked” as a landmark of post-war portraiture, praising its synthesis of formal rigor and emotional depth. It appears regularly in retrospectives that chart Permeke’s transition from grand rural canvases to introspective figural studies, and its influence is seen in later generations of European artists who embraced the nude as a vehicle for existential exploration.

Conclusion

Constant Permeke’s “Standing Naked” (1946) stands as a masterful articulation of vulnerability, resilience, and painterly presence. Through a disciplined composition, earth-rooted palette, and layered brushwork, Permeke transforms a solitary nude into a universal meditation on the human condition. The figure’s protective gesture, sculptural modeling, and interplay of light and shadow invite viewers into a space of intimate reflection, where body and spirit converge. Positioned at the crossroads of his rural Expressionist past and his late introspective phase, “Standing Naked” affirms the enduring capacity of art to reclaim our shared humanity in the face of adversity.