Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions

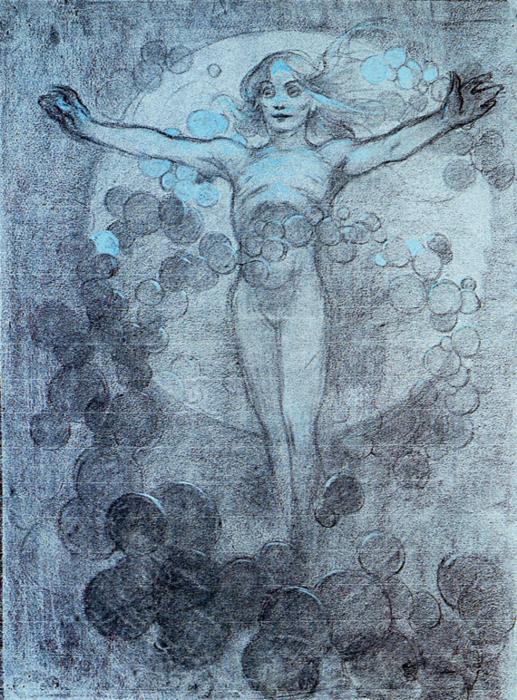

“Standing Figure” (1900) is a compact, monochrome vision in which Alphonse Mucha tests an idea more than he declares a spectacle. A young, nude figure rises at the center with arms extended horizontally, hair drifting outward as if stirred by a quiet current. She is set before a softly drawn circle, and rings of smaller orbs drift around her torso and legs. The drawing is predominantly gray, with cool blue touches that catch on a few of the bubbles and along the body’s upper planes. Unlike the polished color lithographs that made Mucha famous, this sheet is exploratory and intimate, yet its economy carries a persuasive poetry.

Historical Moment

Around 1900 Mucha stood at the height of his Paris renown. He had already transformed the poster into an art form and was moving toward larger, more ideal projects that fused allegory, pattern, and spiritual resonance. This drawing corresponds to that hinge. It is not a theatrical advertisement but a studio meditation that rehearses the visual grammar he would continue to refine—circular halos, floating motifs, and an idealized, emblematic figure. The sheet sits between the commercial demands of the 1890s and the more philosophical ambitions that led to his later cycles.

Subject And Allegory

The title “Standing Figure” sounds plain, but the image is more than a neutral study. The circle behind the head functions like a halo or lunar disk. The clusters of orbs behave like bubbles, stars, or beads moving through water or ether. The figure’s open arms and slight upward tilt suggest arrival or emergence. Read one way, she is surfacing through water, ringed by bubbles that cling and drift as she rises. Read another way, she is a cosmic personification suspended among planets. Mucha avoids literal props and lets the geometry do the symbolic labor, allowing viewers to move freely between natural and metaphysical interpretations.

Composition And Geometry

The drawing organizes itself around a set of concentric and spiraling circles. The biggest is the pale disk behind the figure. It locates her in space and stabilizes the composition, much as an oculus stabilizes a façade. The streaming bubbles expand that geometry outward in asymmetrical swirls, heavier at the lower left and upper right, so the composition breathes rather than locks. The figure’s outstretched arms establish a horizontal that counters the sheet’s vertical thrust and the circle’s roundness. These few axes—horizontal arms, vertical body, enveloping circle—give the sketch lucid order even at its most tentative edges.

Pose And Anatomy

Mucha chooses a frontal pose, rare in his more decorative panels but ideal for testing balance and proportion. The arms form a straight bar across the chest; the legs taper toward a single stance. Nothing about the anatomy is aggressively descriptive; it is simplified to serve the emblem. The small head and elongated torso accent the sensation of lift, while the thighs and calves remain lightly indicated so that contour, not muscle, does the work. The gesture is neither cruciform nor balletic; it is a neutral openness that can accept multiple readings—floating, blessing, or greeting.

Linework And Modeling

The artist builds the figure with a mix of continuous contour and soft interior shading. A steady graphite or charcoal outline runs along shoulders, flanks, and thighs, then loosens in the hands where fingers are suggested rather than specified. Within the contour, smudged tonal fields model chest, abdomen, and upper legs. Mucha relies on the grain of the paper to break up the graphite, letting the skin read as luminous rather than polished. The bubbles are handled with even lighter pressure, their edges often no more than a whispering circle that fades as it turns, convincing the viewer that these forms are translucent and in motion.

Light And Tonal Design

Light appears to emanate from the front-left, but the more powerful effect is the contrast between body and background disk. The figure is slightly darker than the circle, which causes her to read as volume against a soft, radiant ground. Select highlights—the bridge of the nose, the clavicles, the top of the forearms—are lifted with light strokes or erasures, while the abdomen and lower legs sink into a mellow midtone. The tonal plan is deliberately narrow. Such restraint models a body without destroying the atmospheric unity that the drawing depends upon.

The Circle Motif As Meaning

Circles are not a decoration pasted onto the figure; they are the image’s thought. The large disk stabilizes; the small ones mobilize. Together they propose a world without corners, a world of continuities and returns. In Mucha’s iconography, the circle often signals perfection, eternity, or the presence of an ordering force. Here it also creates a gentle pressure that seems to lift the figure. The ring of orbs moving across the torso acts like a belt of energy, a midline current marking the transition between what was below and what now rises into view.

The Role Of Blue

Amid the grays, faint blue highlights appear on several bubbles and along the upper chest and shoulders. These touches are few but crucial. They cool the composition, hint at moisture or air, and distinguish select orbs from the rest, as if catching stray glints. Blue also separates the divine from the earthly in traditional color rhetoric; in a drawing this pared down, a whisper of blue is enough to pull the sheet toward the visionary. Mucha’s control shows in the sparing use of this accent: too much would break the mood; too little would fail to clarify the material quality of the bubbles.

Space, Depth, And Suspension

There is a calm ambiguity to the space. The circle behind the figure could be a disc at some distance or a halo pressed tight to her back. The bubbles overlap and scale down as they recede, giving a sense of depth without a conventional background. The figure’s feet vanish before meeting a ground plane, so we accept suspension as the default condition. The absence of a horizon or architectural prop keeps the drawing from locating itself in a literal world. That decision preserves the allegorical charge and allows the viewer to hover with the subject.

Process And Purpose Of The Study

Everything about the sheet—paper tone, graphite handling, open edges—indicates a working study rather than a finished presentation drawing. Such studies in Mucha’s practice serve several functions. They test proportion and pose, they map the interplay of figure and ornament, and they audition a symbolic language before it is translated into color and print. The disciplined geometry here suggests that Mucha was exploring how a body could inhabit a field of circles without being swallowed by it. The outstretched arms and central axis are practical solutions that might later support typography or framing devices in a poster or panel.

Difference From The Polished Panels

When placed beside Mucha’s full-color decorative prints from the same period, this drawing reveals the skeleton beneath the costume. In the prints, hair blooms into arabesques, garments fall in orchestrated folds, and borders knit the whole into architecture. Here there is no garment to dignify or distract. One watches the artist allocate emphasis: secure the pose, float the orbs, test the halo, keep the face serene. The result has a candor unavailable in finished lithographs. It shows how Mucha’s linear intelligence operates before ornamentation, which explains why his ornament always feels structural when it appears.

The Face And Expression

The expression is simple and readable. Eyes open, mouth softly closed, brows relaxed. Mucha resists melodrama; the figure neither smiles nor laments. The neutrality is deliberate because the hour or idea she represents should be legible without being bound to a specific story. Slight darks at the eyes and lips give the head a focal weight within the field of pale values. Hair streams backward from the temples in a few long strands—enough to indicate movement, not so much as to crowd the halo.

Movement And Stillness

At first glance the pose seems static, but the drawing breathes. Bubbles climb and drift; hair lifts; the slight asymmetry of the hands prevents a cruciform stiffness. The left arm extends a little higher than the right, and the hips twist imperceptibly toward the viewer’s left. These micro-tilts embody the state between motion and rest in which a figure may truly feel suspended. Mucha’s broader work often lives in graceful equilibrium; this study demonstrates how he engineers that equilibrium with minimal means.

Symbolist Resonances

The image fits easily within turn-of-the-century Symbolist concerns: rebirth, purification, ascension, the body as vessel of an unseen current. The bubbles read as breath or spirit, the circle as totality or the moon, the nude as the unadorned self. Because the means are graphic rather than painterly, the symbolism arrives without heaviness. Viewers sense meanings rather than being told them. That approach matches Mucha’s temperament—he trusted line and pattern to carry ideas the way melody carries emotion.

Material Surface And Touch

The sheet’s surface looks worked yet tender. Areas of rubbing suggest that Mucha spread tone broadly with the side of the medium, then drew back into it with firmer lines. Occasional erasures reclaim small highlights. Where the bubbles overlap, the pencil pressure lightens to keep transparency credible. The drawing feels touched rather than labored, a record of decisions as much as of forms. That tactility is part of its appeal; one experiences the artist thinking with his hand.

Relation To Decorative And Applied Arts

Mucha continually translated between fine art and applied design—posters, jewelry, architecture. The strict circular grammar of this sheet would serve any of those domains. The motif could crown a poster, enliven a panel, or become a medallion for metalwork. The floating orbs could transform into pearls or stones in a jeweler’s sketch. Seeing a study at this stage reveals how Mucha conceived images capable of movement across media without losing coherence.

Emotional Tone

What lingers after looking is calm. The drawing does not strain for effect; it invites breathing at its tempo. The centered figure, the low-contrast palette, and the repetition of circles create a meditative pulse. Even the small blue notes contribute to tranquility. It is an image that steadies the viewer—a quality that explains why Mucha’s work thrived not only on the street but also in the home, where images must live with us day after day without exhausting attention.

Legacy And Significance

“Standing Figure” matters because it exposes Mucha’s thinking at the level of essentials. It shows how a human form can hold its own inside a field of ornament, how a symbol can be proposed without props, and how a drawing can remain open to multiple meanings while carrying a perfectly clear mood. For students of his style, the sheet is a primer in the conversion of line and geometry into feeling. For viewers, it is a quiet encounter with ascent, buoyancy, and balance.

Conclusion

In a few tones and a handful of lines, “Standing Figure” builds a world. A central body opens its arms; a circle steadies the space; smaller orbs drift like breath. The medium is modest, the means are spare, and the effect is contemplative. The drawing captures the moment when Mucha’s decorative intelligence meets his symbolist imagination, yielding an image that can live as study, emblem, or promise. It is a reminder that behind every lush panel stands a sheet like this—clear, thoughtful, and sufficient.