Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

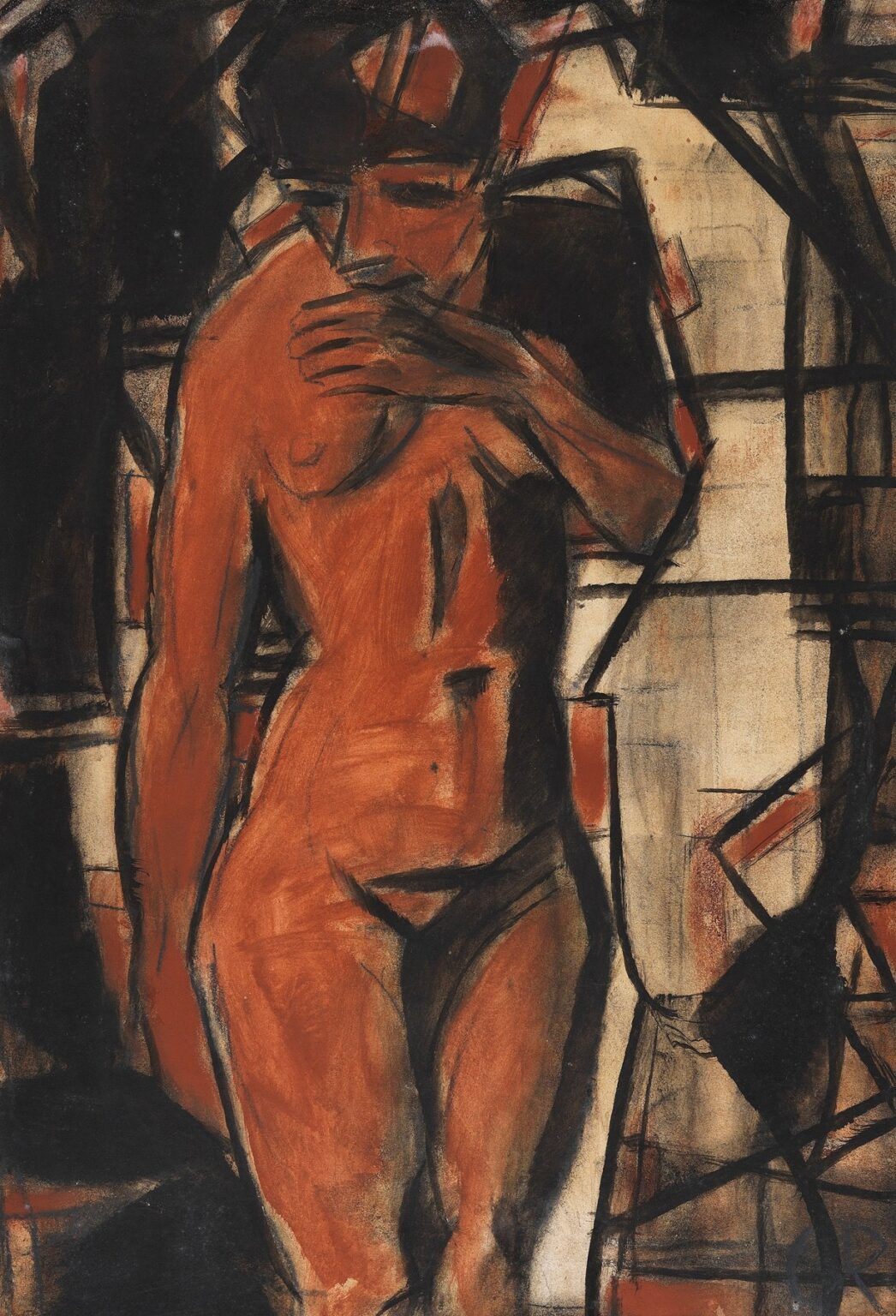

Christian Rohlfs’s Standing female nude (1925) presents a commanding fusion of figural presence and painterly abstraction. Rather than offering a serene, classical portrayal of the human form, Rohlfs confronts the viewer with a figure rendered in intense, earthy hues and outlined by dynamically fractured lines. In this work, the standing nude becomes a stage for exploration of space, volume, and emotion—an embodiment of Expressionist conviction that inner experience can be conveyed more powerfully through bold form and color than through meticulous realism. Over the course of this analysis, we will examine the painting’s historical moment, the artist’s evolving style, the formal strategies at play, and the enduring resonance of this striking image within the trajectory of twentieth-century art.

Historical Context

The mid-1920s in Germany were years of cultural vibrancy shadowed by political and economic uncertainty. The fragile Weimar Republic faced hyperinflation, social upheaval, and the lingering trauma of the First World War. Yet amid these challenges, Berlin and other German cities teemed with artistic experimentation. Expressionism, which had surged before and during the war, evolved into a more introspective mode that probed the human psyche and the body’s capacity to register emotional states. Christian Rohlfs—then approaching his late seventies—had long since turned away from his early naturalism, embracing the expressive potential of color, line, and medium. In Standing female nude, painted in 1925, he synthesizes decades of innovation to produce a work that reflects both personal vision and the broader currents of modern German art.

Christian Rohlfs’s Late-Career Evolution

Born in 1849, Rohlfs’s career spanned an extraordinary range of styles. His early training in Düsseldorf instilled a solid grounding in academic techniques, which he applied to landscapes and genre scenes. A serious illness in the late 1890s precipitated a shift toward etching, watercolor, and pastel—media that encouraged immediacy and direct engagement. Encounters with French Impressionism and Symbolism expanded his palette and his interest in subjective atmosphere. By the 1910s, Rohlfs fully embraced Expressionism, developing a mature style characterized by vibrant tempera on paper, bold charcoal outlines, and a willingness to abstract and fragment form. In 1925, Standing female nude emerges as a pivotal statement: Rohlfs channels decades of experimentation into a composition that balances figural clarity with dynamic abstraction, asserting the nude as both subject and medium.

Visual Description

Standing female nude presents a single figure occupying most of the picture plane. The woman stands in three-quarter view, her weight shifted onto one leg, creating a subtle S-curve in her posture. Her torso, hips, and thighs are rendered in a rich, terracotta red, while her face and limbs recede into areas of deep charcoal black. One arm is bent at the elbow, hand raised to her mouth in a contemplative gesture, while the other falls loosely at her side. Behind her, intersecting bands of black, red, and pale ground color form an abstract grid that suggests architectural or interior space without defining it. The paper’s warm ochre undertone peeks through thin washes and broken lines, lending the scene a muted glow.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Rohlfs constructs the composition around a strong vertical axis defined by the figure’s spine and torso. This upright posture conveys stability and presence, anchoring the work despite the gestural hectic energy of the background. The bent elbow and raised hand introduce a secondary diagonal, directing the viewer’s gaze toward the figure’s face and heightening psychological tension. The background’s crisscrossing lines and blocks of color do not recede like a traditional perspective; rather, they press forward, dissolving the boundary between figure and space. Negative space—the unpainted paper—functions as a visual counterweight, framing the figure’s silhouette and giving the densely worked passages room to breathe.

Color and Light

In Standing female nude, color assumes a symbolic role. The figure’s body, painted in burnt sienna and cadmium red heats, suggests vitality and corporeal presence. These warm tones contrast sharply with the charcoal black that defines contours and shadows, lending the image an almost sculptural relief. Hints of ochre and pale yellow wash illuminate areas of the torso and thighs, as though light filters through—less from an external source than from the figure’s interior. The background’s subtle variations between raw paper, wash, and pigment echo the interplay of light and shadow within the room. Light here is less a vehicle for naturalism than a means of animating forms, turning skin into a living, breathing surface.

Brushwork, Line, and Technique

Rohlfs’s technique in this painting is characterized by an interplay of wet and dry media. He begins with broad, fluid washes of tempera to establish blocky volumes of color. Over these, he applies energetic charcoal or pastel strokes, sketching in musculature, joint articulations, and background geometry with swift, resolute gestures. At times the brush is heavily loaded, producing opaque passages; in others, pigment is thinned to reveal the paper’s texture. The lines vary in thickness and intensity, sometimes crisp and decisive, at others frayed and smeared. This layering of application and subtraction—where strokes are lifted or smudged—creates a tactile surface that gestures toward the artist’s hand rather than masking it. The result is a living, breathing image that embodies movement and emotional register.

The Nude in Expressionist Discourse

Traditionally, the nude has been a trophy of idealized beauty or an object of moral allegory. In the Expressionist context, however, the body becomes an extension of the psyche—a canvas onto which internal states are projected. Rohlfs’s nude participates in this shift. The figure is neither eroticized nor classical; she is introspective, even guarded, as indicated by her partially obscured face and protective hand gesture. The emphasis on raw color and fractured space underscores the tension between flesh and environment. By refusing to smooth contours or conceal process, Rohlfs invites viewers to perceive the body as both material fact and emotional symbol, a living landscape shaped by thought and feeling.

Symbolism and Thematic Resonance

Several layers of meaning can be discerned in Standing female nude. The figure’s raised hand to mouth suggests hesitation, contemplation, or perhaps a moment of self-awareness. Her half-turned gaze, nearly swallowed by shadow, hints at vulnerability and introspection. The fractured backdrop—geometric yet incomplete—may represent the fragmentation of modern life or the dissolution of traditional frameworks. The warm-red body set against dark structural lines evokes the tension between organic life and constructed order. Viewed in the context of 1925 Germany, the painting can be read as an allegory for individual identity caught between inner impulses and external constraints, a theme that resonates with broader social and psychological anxieties of the era.

Relationship to Rohlfs’s Oeuvre and Contemporary Art

Standing female nude stands among Rohlfs’s most accomplished late works, synthesizing his earlier plein-air light studies, his Symbolist explorations of mood, and his mature Expressionist emphasis on form and gesture. Compared to his floral still lifes—where color often took center stage—this figural piece emphasizes line and volume. In the broader modernist panorama, Rohlfs parallels the concerns of contemporaries such as Otto Mueller, whose figures also emerge from abstracted spaces, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, whose nudes pulsate with inner intensity. Yet Rohlfs’s unique commitment to tempera and pastel on paper, and his visible layering process, set him apart from both his peers and the oil-dominated avant-garde.

Reception and Legacy

While Rohlfs never sought avant-garde notoriety, his late works gained renewed appreciation after his death in 1938. During the Nazi era, Expressionist works were condemned, but many of Rohlfs’s paintings—especially those with non-political subjects—remained in private and museum collections. Mid-20th-century retrospectives reevaluated his contributions, situating him as a bridge between pre-war Expressionism and post-war abstraction. Standing female nude has since been recognized as a key example of figural Expressionism, influencing later artists who sought to reconcile bodily presence with abstract technique. Its preservation in major collections attests to its enduring power and the subtlety of Rohlfs’s late vision.

Conclusion

Christian Rohlfs’s Standing female nude (1925) is a testament to the artist’s lifelong quest to reveal inner life through form and color. By combining the solidity of the human figure with the dynamism of fractured space, Rohlfs creates an image that feels both timeless and acutely modern. The painting’s raw energy, its fusillade of brush and charcoal strokes, and its tension between presence and abstraction continue to captivate viewers. Above all, it stands as a reminder that the nude—far from a static genre convention—can serve as a profound vessel for examining identity, emotion, and the unceasing dialogue between artist and medium.