Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

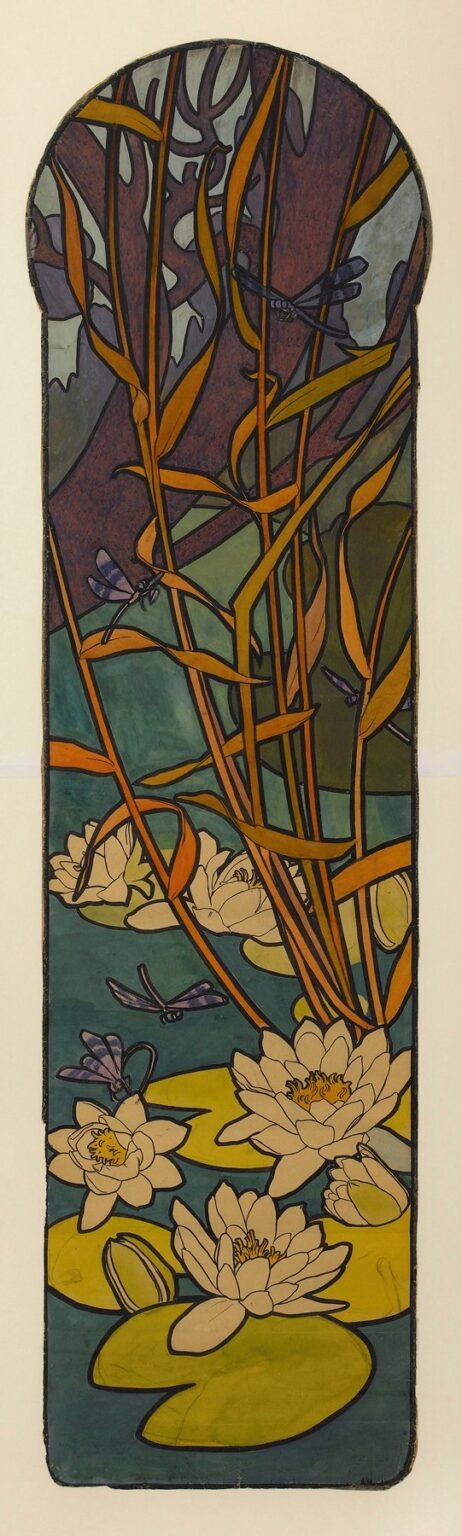

Alphonse Mucha’s design for the Stained Glass Box for Fouquet Jewelry (c. 1901–02) exemplifies the artist’s power to transform a utilitarian commercial object into a jewel-like work of Art Nouveau craftsmanship. Rather than a static poster, this piece is conceived as the decorative lid of a glass presentation box—an intersection of fine art, decorative arts, and luxury branding. Through its sinuous vegetal forms, stained-glass color harmonies, and symbolic allusions to monastic tradition, Mucha’s composition elevates everyday commerce into a ritual of beauty and refinement, perfectly suited to encase and showcase the precious contents within.

The Commission and Context of Luxury Display

At the turn of the twentieth century, Paris stood at the apex of luxury culture. The city’s jewelers, perfumers, and high-end merchants competed not only in the quality of their wares but in the artistry of their display and packaging. Fouquet, a Trappistine order–backed liqueur famed among society’s elite, recognized that presentation could transform the act of purchase into an aesthetic experience. They commissioned Mucha—already celebrated for his theatrical posters and decorative panels—to conceive a stained-glass lid that would crown their jewelry box. The intent was twofold: to protect and enshrine the jewelry and to offer a marvel of decorative art that would linger in the memory of discerning clientele.

Compositional Architecture: Arches, Circles, and Rhythmic Vines

Mucha’s design is anchored by an arched lid, its pointed top recalling the tracery of Gothic cathedral windows. This ecclesiastical reference alludes to the Trappistine heritage behind Fouquet’s brand, evoking sacred spaces and fostering an atmosphere of devotion. Within the arch, a large circular medallion occupies the upper third of the composition, its rim studded with repeating quatrefoil motifs resembling stylized Cistercian crosses. From this orb, sinuous vines emerge, cascading downward in parallel columns that interweave with the border’s straight lines. Beneath, water lilies bloom atop lily pads, while dragonflies hover—natural motifs that imply purity, transformation, and the fleeting beauty of life. The viewer’s eye travels from the apex of the arch, through the sacred circle, down along the serpentine vines, and onto the serene aquatic scene, tracing a path that mirrors both spiritual ascent and contemplative descent.

Color Palette: Stained-Glass Hues and Luminous Interplay

Although only preparatory drawings survive in Mucha’s hand, his instructions to the glassmakers called for translucent panes in amber, rose, pale mauve, and soft green—all colors that resonate with the gemstones displayed within the box. The amber vines would catch overhead light and glow like molten gold; the rose and mauve backgrounds would infuse the interior with a gentle warmth; the pale green lily pads would serve as a cool counterpoint, evoking tranquil ponds. The dragonflies, painted in delicate violet and blue, would flicker across the surface. By choosing a palette rooted in nature’s own harmonies—and in the precious materials of luxury—the design ensured that the jewelry’s sparkle and colorfulness would be enhanced, rather than overwhelmed, by its architectural setting.

Line, Form, and the Art Nouveau Idiom

Line work is the lifeblood of Mucha’s style, and here it assumes three-dimensional form. The metal came (the lead or brass strips that bind stained glass) would follow Mucha’s fluid contours, creating each undulating vine with a single, unbroken stroke. Inside each vine, delicate hairlines in the glass were to be etched or painted, capturing the veins of leaves and the segmentation of dragonfly wings. This interplay of bold structural lines and fine interior detailing is typical of Mucha’s posters but rendered here as sculptural ornament. The repetition of the quatrefoil circle—a geometric counterpoint to the organic vines—speaks to his belief in harmonizing nature and geometry, a hallmark of Art Nouveau’s decorative advances.

Symbolism: Botanical and Spiritual Allusions

Every motif in the “Stained Glass Box” carries symbolic resonance. The vine—an ancient emblem of growth, connection, and divine mystery—evokes monastic viticulture and the sacramental wine produced by Trappistine monks. Water lilies—symbols of purity and rebirth—float tranquilly at the bottom, suggesting a serene foundation beneath the more dynamic upper ornament. Dragonflies, creatures of transformation and light, underscore the idea that beauty is fleeting and must be treasured. The quatrefoil circles recall the Cistercian cross, linking the design to the liqueur’s monastic origins without overt religious imagery. In uniting these symbols, Mucha created a visual narrative: luxury as a sacred rite, the jewelry as vessels of beauty, and the box as a hortus conclusus—a walled garden of wonder.

Technical Execution: From Drawing to Glass

Transforming Mucha’s design into an actual stained-glass lid required extraordinary collaboration between artist and craftsmen. Each vine and motif was first drawn full-scale on paper, then transferred to glass using carbon or grease pencils. Glass sheets—hand-blown or machine-pressed—were cut to shape, with edges ground smooth. The came was forged in slender strips, heated, and bent to follow the curves. Glass paint and vitreous enamel were applied for shading—particularly on the dragonflies’ wings and the lilies’ petals—then kiln-fired for permanence. The completed panels were assembled, waterproofed with putty, and set into a metal frame. This blend of fine art drawing and centuries-old stained-glass technique embodies Mucha’s ideal of gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art.

Integration of Function and Beauty

What distinguishes Mucha’s “Stained Glass Box” design is its uncompromising unity of form and function. The lid must be sturdy enough to protect the jewelry, yet transparent enough to display it. The ornament must not obscure the contents, yet must attract immediate attention. Mucha solved these challenges by concentrating ornament in the upper half—around the arch and circle—while reserving the lower field for simpler water-lily vistas that subtly frame, rather than compete with, the jewels. The viewer’s gaze is first drawn to the dramatic top, then glides downward to discover the treasures below. This choreography of sightlines transforms opening a jewelry box into a multi-stage visual experience.

Reception and Influence

Although no intact examples of the Fouquet stained-glass lid survive in public collections, period photographs and archival records attest to its existence and impact. The design inspired other luxury houses—perfume makers, letterpress stationers, and porcelain manufacturers—to commission decorative packaging and display objects from fine artists. Mucha’s approach demonstrated that even mundane objects—jewelry boxes, in this case—could serve as canvases for artistic innovation, enriching the consumer experience. The concept of branding through decorative art, which he helped pioneer, would echo throughout the twentieth century in luxury goods, interior design, and even modern packaging.

Legacy in Contemporary Design

Today, Mucha’s “Stained Glass Box” resonates with designers who seek to infuse digital and manufactured products with hand-crafted warmth. Laser-etched acrylic panels, backlit installations, and printed glass facades often trace their lineage to Mucha’s integration of light, line, and ornament. The symbolic motifs—vines of connection, flowers of rebirth, insects of transformation—continue to appear in branding, packaging, and interior architecture. Moreover, the project anticipates modern pop-up retail and experiential marketing, where product presentation becomes an immersive art installation. Mucha’s vision that functional objects can also be works of art has never been more relevant.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Stained Glass Box for Fouquet Jewelry” represents a high point of Art Nouveau’s fusion of beauty and utility. Through its soaring arch, glowing palette, and layered symbolism, the design transformed a glass lid into a sacred gateway to luxury. Mucha’s virtuoso line work and deep understanding of materials enabled craftsmen to realize a lid that not only protected but also glorified the jewelry within. Over a century later, this project stands as a testament to the power of decorative art to elevate everyday objects, reminding us that true luxury lies not merely in the contents of a box, but in the artistry that frames and encloses them.