Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

Alphonse Mucha’s design for the Stained Glass Box for Fouquet Jewelry (c. 1901–1902) stands as a singular testament to his capacity for translating the fluid ornamentation and organic motifs of Art Nouveau into three-dimensional decorative objects. Rather than a conventional poster or print, this piece was conceived as the decorative lid of a glass display box—a functional yet highly artistic container for precious jewels. Combining architectural framing, sinuous vegetal forms, and a nuanced palette reminiscent of stained glass, Mucha created an integrated design that both showcased the beauty of the jewelry within and embodied the ideals of the period’s gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Through a layered exploration of its historical context, compositional ingenuity, color harmonies, ornamental language, technical execution, and enduring influence, we can appreciate how this jewel box lid stands at the intersection of fine art, applied design, and commercial luxury.

Historical and Cultural Context

At the turn of the twentieth century, Paris flourished as a nexus of luxury goods, high fashion, and avant-garde art. Wealthy clientele sought ever more refined expressions of taste, commissioning artists and designers to create bespoke objects that combined functionality with aesthetic innovation. Jewelry house Fouquet, famous for its exquisite gems and refined clientele, recognized that presentation could enhance perceived value. In this context, Alphonse Mucha—already celebrated for his theater posters and decorative panels—was invited to lend his stylistic signature to a display case lid. The resulting design reflects both the era’s fascination with nature-inspired ornament and the emerging Art Nouveau emphasis on integrated artistry across mediums, where packaging and interiors became canvases for creative expression.

Commission and Purpose

The commission tasked Mucha with creating a lid for a glass box intended to exhibit Fouquet’s finest pieces—necklaces, brooches, and tiaras—in a retail or salon setting. The lid needed to be both protective and visually compelling, drawing the eye to the treasures inside while unifying the object as an example of total design. Mucha approached this challenge by designing an arched metal framework that would support colored glass panels embellished with his trademark sinuous vines and stylized leaves. The focus was not merely on decorative surface treatment but on ensuring that light passing through translucent glass would cast jewel-like reflections, harmonizing with the gemstones displayed beneath. This functional imperative—enhancing the jewelry through interplay of light, color, and form—guided every aspect of Mucha’s approach.

Composition and Spatial Organization

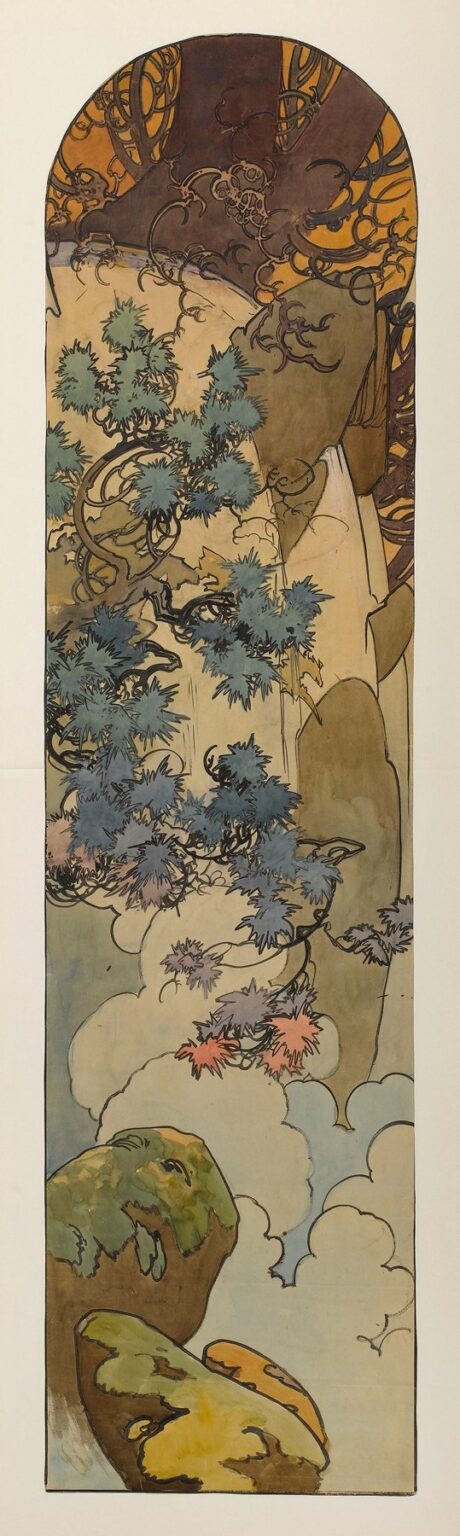

The composition of the Stained Glass Box lid is defined by its tall, arched shape, reminiscent of a church window or a Gothic clerestory—an architectural allusion that lends the design a sense of reverence. At the very top, interlaced metal curves form a pointed arch, their lines echoing the tracery of medieval cathedrals. Beneath this, a large circular motif occupies the central portion of the arch, serving as a halo or focal point. From this circle emanate sinuous, vine-like shoots that cascade downward in a rhythmic pattern, interweaving with stylized leaves. The lower section of the arch transitions into a flatter base, where gently undulating clouds or patterned backgrounds fill the remaining space.

This arrangement guides the viewer’s eye from the apex of the arch—evoking spiritual uplift—down through the vegetal proliferation to the jewelry below. The circular motif provides a moment of visual pause, as though inviting contemplation, before the richer density of vines and foliage draws the gaze further downward. Mucha’s orchestration of circular, arched, and linear elements creates a dynamic yet balanced spatial flow that mirrors the experiential journey of encountering precious objects within the box.

Color Palette and Light Effects

Although Mucha’s surviving presentation drawing offers a limited palette of muted browns, ochres, and pastel blues, the design was intended to be executed in translucent stained glass of complementary hues. The top arch tracery would appear in shimmering gold or amber glass, catching overhead lighting and creating a warm glow. The central circle, framed by concentric ornamental rings, was envisioned in soft rose or lavender tones, contrasting with the deeper greens and blues of the trailing vines and leaves below. These color choices reflect the preciousness of the jewelry itself—rose quartz, amethyst, jade—and would harmonize with the gemstones displayed inside.

Importantly, the interplay of light and color was integral to the concept: natural or artificial illumination would filter through the glass, casting kaleidoscopic shadows across the box’s contents and surrounding surfaces. This luminous effect not only dramatized the jewelry but also reinforced the visually poetic language of Art Nouveau, in which light and color fused to evoke natural rhythms and emotional resonance.

Line Work and Art Nouveau Curves

Mucha’s hallmark lies in his mastery of line, and the Stained Glass Box design exemplifies his ability to translate two-dimensional fluidity into three-dimensional ornament. The metal framework’s curves mirror the graceful contours of vines, with each tendril rendered as a continuous, confident stroke. Even in the preparatory drawing, one senses the rhythmic energy of these lines, as they coil, twist, and branch overhead. The circular motif’s border features a sequence of repeated quatrefoil or Celtic cross patterns—each outlined in bold tracery—establishing a measured counterpoint to the more freely flowing vegetal forms.

The leaves themselves are stylized into spiky, almost artichoke-like clusters, their tips defined by fine hairline strokes that would translate into thin metal filigree or lead came in the completed glass panels. By varying line thickness—thicker for the structural arch lines, thinner for interior decorative details—Mucha ensures visual hierarchy and structural clarity. This deft modulation of line weight would have guided metalworkers in crafting the supportive framework, ensuring both beauty and stability.

Symbolic Motifs and Natural Imagery

Symbolism permeates the Stained Glass Box design, with the floral and vegetal motifs echoing broader Art Nouveau themes of renewal, growth, and the living world. The vine is an ancient symbol of abundance and connection, historically tied to Dionysian rites and Christian iconography alike. Here, it suggests the flourishing creativity and wealth embodied by Fouquet’s jewels. The circular motif may reference the sun or the eternal cycle of nature, implying that the beauty contained within the box—like the natural world—transcends fleeting trends.

The arch itself evokes cathedral windows, imbuing the object with a sense of sacredness. The viewer is invited to regard the jewelry within as precious relics, much like devotional artifacts behind church glass. This interplay of secular luxury and spiritual allusion was a characteristic strategy of the period, allowing commercial objects to tap into deeper cultural and emotional associations.

Materials, Technique, and Craftsmanship

The transition from Mucha’s paper design to a realized glass and metal lid required collaboration with skilled artisans—glassblowers, leadworkers, and metal smiths. The design called for stained-glass panels cut to the intricate shapes of vines and leaves, each piece selected for hue consistency and translucency. These panels would be set into a supportive network of wrought-iron or brass came, forged to the undulating curves specified in Mucha’s drawing. Rivets or solder joints at each intersection needed precise alignment to maintain both aesthetic integrity and structural strength.

Furthermore, the central circular medallion might have incorporated painted glass or enamel overlays to achieve the detailed quatrefoil patterns, requiring kiln-fired enamels or acid-etched details. The overall workmanship had to balance the fragility of glass with the durability needed for retail display. Mucha’s involvement extended to advising on the selection of glass colors, finishes (e.g., opalescent vs. transparent), and the optimal thickness of metal strips to prevent warping while preserving the delicate line quality.

Influence of Japonisme and Celtic Ornament

Mucha’s ornamental vocabulary in this design reflects both Japonisme—the late nineteenth-century European fascination with Japanese aesthetics—and a revival of Celtic and medieval motifs. The sweeping curves and abstracted natural forms recall Japanese woodblock prints’ emphasis on asymmetry and the dynamic interplay of positive and negative space. The quatrefoil medallions within the circular halo evoke Celtic crosses and medieval cloister motifs, integrating Western historical ornament into a modern idiom. This eclectic synthesis was typical of Art Nouveau, which sought to transcend narrowly academic styles by mining global and historical sources, then reimagining them through an organic, unified lens.

Relationship to Mucha’s Other Decorative Works

The Stained Glass Box design shares compositional affinities with Mucha’s luminous decorative panels—such as his beloved Seasons series—where female figures are framed by circular mandorlas and surrounded by swirling botanical motifs. Here, the human figure is absent, yet the design retains the same sense of rhythmic vitality and reverent framing. The absence of a central figure underscores the object’s function as a display surface, yet the living energy of the vines animates the form in much the same way that Mucha’s women do in his posters. This object thus extends Mucha’s artistic agenda—integrating art into everyday life, whether through walls, windows, or, in this case, jewelry boxes.

Reception and Legacy

Although the original Stained Glass Box lid for Fouquet has not survived in public collections, Mucha’s preparatory designs circulated widely among collectors of his graphic work, and photographic reproductions appeared in design journals of the time. The concept of the jewel box as a canvas for high art inspired other luxury firms—perfume houses, Parisian ateliers, and fine chocolate makers—to commission decorative lids and packaging from leading artists such as Eugène Grasset and Henri Privat-Livemont. Mucha’s pioneering integration of stained glass techniques into product display anticipated later twentieth-century collaborations between artists and manufacturers, from Tiffany’s glass lamps to modern architectural facades.

Today, designers reference Mucha’s approach when seeking to add narrative depth to product packaging—whether through laser-cut metalwork, translucent acrylic window boxes, or digitally printed glass panels. The Stained Glass Box design remains a touchstone for how a simple functional object can become a vessel of beauty, history, and cultural resonance.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s Stained Glass Box for Fouquet Jewelry exemplifies the Art Nouveau ideal of gesamtkunstwerk, where art and utility merge seamlessly. Through a masterful composition of architectural forms, organic vines, and symbolic motifs, Mucha created a lid that elevated the act of display into a ritual of aesthetic appreciation. His nuanced palette and virtuosic line work guided craftsmen in realizing a luminous stained-glass and metal object, one that enhanced both the visibility and the symbolic weight of the jewelry it protected. Although the physical box may no longer exist, the surviving designs testify to Mucha’s pioneering vision: that every surface, no matter how utilitarian, is an opportunity for art to enrich daily life and to frame luxury as a harmonious encounter of light, color, and form.