Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

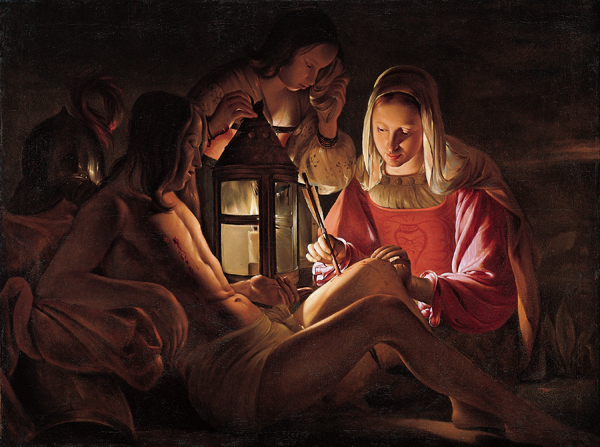

Georges de la Tour’s “St. Sebastian with Lantern” (1630) transforms a moment of care after martyrdom into a radiant nocturne. Under the glow of a lantern, the wounded Sebastian reclines as a woman—traditionally identified as Saint Irene—leans forward to extract an arrow from his thigh. A second attendant bends over the lantern, adjusting its shutter so the beam falls exactly where the healer needs it. The rest of the scene recedes into a velvet dark, so that flesh, cloth, and flame become the entire vocabulary. De la Tour distills pathos into quiet precision: not the public spectacle of execution, but the intimate labor of tending a body—hands, eyes, and light coordinated to rescue life.

Composition as Theater of Care

The painting’s architecture is triangular, with the lantern at the apex and the three figures forming the points of a close-knit circuit. Sebastian’s diagonal body runs from lower left toward center, a soft ramp that delivers the viewer’s gaze to Irene’s focused gesture. Irene’s torso and sleeve build a second diagonal that returns light to the wound; the attendant behind the lantern provides a third stabilizing angle. These vectors converge at a single, modest climax—the arrow and the hand that removes it. By making the composition spiral toward a tiny act, de la Tour asserts that care itself is dramatic enough to command a canvas.

Lantern Light as Moral Weather

In de la Tour, illumination is not decoration but decision. Here the lantern organizes the entire moral climate. Its flame is hidden behind glass, yet the light it casts is palpable and directional, wrapping Sebastian’s torso in a honeyed gradient, catching the satin of Irene’s sleeve, and harvesting small highlights along the arrow shaft and fingertips. The lantern’s panes produce subtle planes of brightness that echo the surgeon-like discipline of the scene. Darkness protects the rest, turning background into silence so that attention can settle where healing happens. This weather is tender: light is rationed, placed, and shared.

The Roles of the Three Figures

Sebastian, bound and pierced in the traditional story, appears here not as a heroic pin cushion but as a human patient. His head leans away, features relaxed to the edge of sleep, muscles slack from exhaustion. Irene’s role is neither mournful nor ecstatic; she is practical, exact, and courageous, a saint of method. The attendant—perhaps a maid or helper—acts as a living reflector. By admitting women as protagonists of rescue, de la Tour shifts the story’s emphasis from spectacle to compassion, from male martyrdom to female agency and competence.

Gesture, Hands, and the Ethics of Touch

Hands are the painting’s expressive engine. Irene’s left hand cradles the flesh around the wound, not squeezing but steadying; her right hand pinches the arrow with sure economy, the thumb’s pressure made visible by a small crescent of highlight. The helper’s fingers adjust the lantern’s shutter with equal finesse. Sebastian’s hands, by contrast, rest open and inactive, suggesting surrender to care and trust in those who minister. De la Tour’s hands carry ethical weight: they demonstrate a craft that is intimate without presuming, exact without violence.

Flesh, Cloth, and Material Truth

The painter renders Sebastian’s body with large, unbroken planes that drink the lantern’s warmth—pectorals, ribcage, hip, and thigh read as sculpted volumes rather than anatomical bravura. Irene’s garments—rose mantle, cream bodice, and headcloth—are modeled as living fabrics: the mantle’s satin throws long, soft reflections; the linen kerchief steadies the head like a frame; the bodice glows where the lantern finds it and deepens to wine where it falls away. The helper’s sleeve and cuff absorb light with a matte hush. These materials are not props; they are partners in the act. Light passes from glass to cloth to skin as if compassion had a physical route.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

The palette is restrained: lamp-warmed flesh tones; muted rose and cream in Irene’s dress; deep olives and browns in background and hair; a cooler gray on the lantern’s frame. Because chroma is limited, temperature does the emotional work. Warmth concentrates where life and labor reside—the wound, the hands, the faces—while cooler notes collect at the perimeter, keeping mood and narrative sober. The pink of Irene’s mantle is not a sentimental flourish; it’s a calibrated warmth that aligns her with the life she protects.

Iconography Reconsidered

Sebastian is traditionally shown tied to a tree or post, bristling with arrows. De la Tour chooses another moment: the rescue by Saint Irene that emerged in post-medieval legends. The lantern replaces the public stage with a private clinic; the arrow becomes a medical problem, not merely a symbol of persecution. This change furthers the artist’s larger program of trimming iconography to essentials. The visible sanctity here is not a halo but attention. The miracle is method.

The Lantern as Studio and Symbol

Structurally, the lantern functions like a mobile studio lamp—a controlled source making the scene legible and honest. Symbolically, it proposes a theology of small light: grace that one can carry, focus, and share. The helper’s act of “aiming” the beam becomes an emblem for the entire painting’s ethic—light is a resource to be stewarded toward what matters most. The lantern’s glass also grants a quiet metaphor for body and soul: fragile enclosure around living fire.

Space, Silence, and the Chamber of Healing

The setting is pared to near-void. A soft ground and a hint of horizon—or the edge of bedding—are all we’re given. This subtraction is not poverty; it is respect. By withdrawing the usual scenic apparatus, de la Tour builds a chamber of healing where gestures can resonate. The darkness is thick enough to feel like privacy; the viewer enters as a companion rather than a spectator. The room’s silence is the work’s co-author.

Chiaroscuro Tempered by Calm

The single light source and deep shadow place the canvas within the Caravaggesque tradition, but de la Tour’s temperament is different. He resists theatrical shock and favors calibrated transitions: flesh turns with long, quiet modulations; edges soften and sharpen with exact timing; highlights are rationed like medicine drops. This composure converts chiaroscuro from drama into ethics—light that clarifies without humiliating, shadow that protects without hiding.

Rhythm, Breath, and the Time of Healing

Though still, the painting has a slow pulse. We feel the timing of breath: Sebastian’s chest rising, Irene’s patience measured in the careful withdrawal of the arrow, the helper’s steady hand keeping the beam consistent. Even the lantern’s flame suggests tempo; the viewer senses a minute-by-minute rescue rather than a thunderclap miracle. De la Tour’s nocturne is a chronicle of minutes well-spent.

The Face as Instrument of Care

Irene’s face is lit from below, a difficult angle that can distort features into melodrama. Here it dignifies them: cheek and brow become simple, strong planes; the eye concentrates without strain; the mouth rests between compassion and control. Sebastian’s face is set in profile shadow so the scene avoids sentimental exchange of glances. Healing does not require eye contact; it requires expertise. The helper’s head leans toward the beam, a portrait of cooperative focus.

The Wound as Point of Convergence

Every formal choice converges on the wound. Composition spirals to it; light focuses on it; color warms around it; gesture resolves at it. Yet de la Tour refuses gore. The puncture is clean; a trace of blood is subdued; the drama lies in the removal, not the injury. This restraint dignifies both the subject and the viewer. It also registers theological confidence: what needs attention is not the spectacle of damage but the fidelity of remedy.

The Painter’s Discipline and Surface

De la Tour achieves persuasion with a technique that disguises itself. He lays flesh and fabric in broad tones before passing back with small, decisive accents—the shine along the arrow, the narrow light on a knuckle, the soft glimmer on satin. Edges are chosen rather than generalized: crisp where arrow meets air, softened where limb retreats into shadow, firm where hand anchors flesh. Nothing is fussy; everything is earned. The surface supports the story the way a good bandage supports healing—securely and without calling attention to itself.

Dialogue with the Artist’s Other Nocturnes

Placed alongside de la Tour’s Magdalene by candlelight or his “Newborn,” this canvas shares a consistent ethic: domestic scale, single-source light, and gestures that turn ordinary acts into sacraments of attention. What is distinctive here is the triad of cooperation—patient, healer, and light-keeper—forming a community of care. The work thereby enlarges the painter’s nocturnal world from solitary contemplation to shared labor.

Humanism Without Sentimentality

The picture values bodies as they are: Sebastian’s vulnerable torso; women’s practical hands; the honest fatigue of posture. There is no cosmetic heroism, no theatrical piety. Yet the canvas is not cold. Its warmth lies in fairness: every figure receives the same truthful light; every object—the lantern, the arrow, the cloth—gets the respect of exact depiction. The result is a humanism grounded in seeing clearly and doing kindly.

Modern Resonance

Viewers today can read the scene through the lens of caregiving and medicine. It honors the invisible work of nurses, aides, and companions who adjust lamps, hold skin steady, and make pain manageable. It also offers an image of collaboration across roles and genders—empathy and precision working together. In times when care networks bear heavy loads, the painting’s quiet trio feels both historical and immediate.

The Viewer’s Role

We stand just outside the lantern’s cone, admitted to the circle without being asked to act. The composition trusts us to attend rather than consume. If we match the painting’s steadiness, we become part of the care it depicts: our attention helps hold the light. That is de la Tour’s recurring invitation—look well enough, and looking itself becomes a kind of service.

Conclusion

“St. Sebastian with Lantern” is a nocturne of remedy. With one flame, three figures, and the simplest props—a shaft of wood and an arrow—Georges de la Tour builds a complete ethics of attention. Composition guides the eye to the smallest important thing; color steadies feeling; texture convinces the hand; light behaves like compassion, finding the wound and refusing spectacle. The painting endures because it recognizes that salvation often looks like cooperation at close range: a lamp carefully aimed, a hand precisely placed, a blow undone by skill. In this quiet theater, healing becomes luminous.