Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

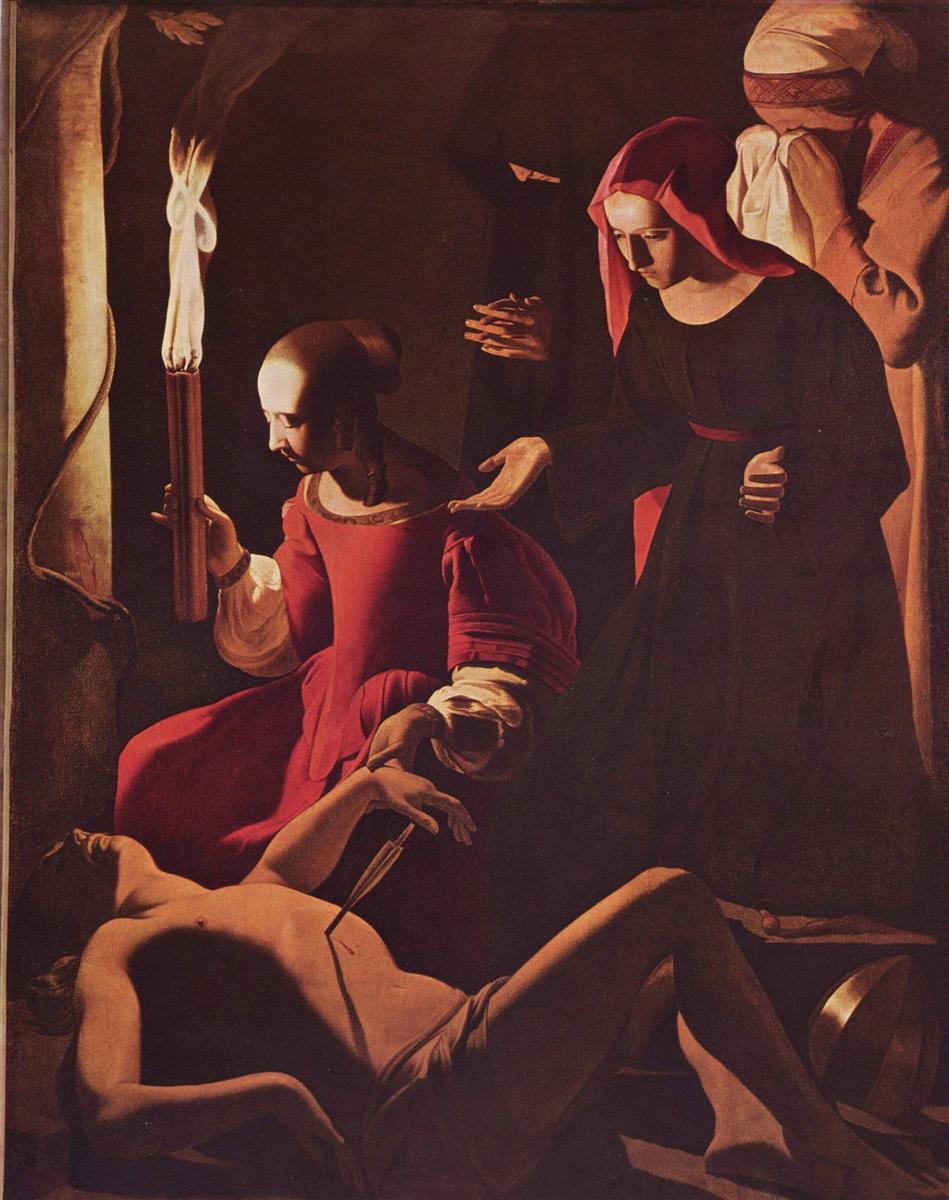

Georges de la Tour’s “St. Sebastian Tended by St. Irene” (1649) is one of the most eloquent nocturnes of the seventeenth century. Painted near the end of the artist’s life, it distills his mature language—one light, few figures, large mute planes—into a scene where compassion takes the place of spectacle. Sebastian’s body, slack and pale, lies diagonally across the foreground, the shaft of an arrow still lodged in his torso. Beside him kneels a woman holding a cluster of bound candles; another, veiled, stands behind, grief folded into her cloth. St. Irene reaches her hand toward the wound with the calm authority of a nurse. The painting replaces the public theater of martyrdom with an intimate rite of care, making the flame a partner in both medicine and devotion.

The Historical Saint and the Painter’s Choice

The Roman soldier Sebastian was condemned to death for his Christian faith and shot with arrows; later, according to legend, he was nursed back to health by Irene of Rome. In early modern Europe he became a protector against plague, his pierced body a metaphor for the city assailed by disease. Many artists chose the explosive moment of execution or the triumphant recovery. De la Tour chooses the interval between—an hour of triage conducted in the thick hush of night. By doing so he turns tragedy into instruction, showing how mercy behaves and how light itself can be a healing instrument.

Composition and the Geometry of Compassion

The composition is organized around intersecting diagonals that model the movement from injury to aid. Sebastian’s limp body forms a long diagonal from lower left to upper right. Irene’s outstretched arm descends toward his wound on a counter-diagonal, creating a visual bridge that converts distance into touch. The kneeling attendant holding the candles anchors the left half of the canvas, her rounded shoulder and bent head forming a compact triangle of stability. The standing figure at right, partially veiled and turned inward, completes a vertical pillar of grief. These masses balance the open space above Sebastian’s chest where attention must settle. The eye travels from flame to face to hand to wound, then returns to the flame, tracing a circuit that mimics the rhythm of care.

Light as Subject, Symbol, and Cure

De la Tour’s light is always more than illumination; it is an ethic. Here the bound candles serve as both source and sign. Their long, fused shafts burn with a clean, steady flame whose pale plume lifts like a prayer. The glow falls first across the kneeling caregiver’s forehead and the cuff of her sleeve, then pours down Sebastian’s torso, modeling muscles and ribs with the compassionate clarity of a physician’s hand. Irene, in a robe dark as night, receives a gentle rim of light along her veil and palm—the sacred economy of attention made visible. Darkness is not menace but shelter, a protective room in which faith and skill can act without interruption. In this chiaroscuro, light functions as the medicine that reveals what must be done.

The Silence of De la Tour’s Chiaroscuro

Although the painting belongs to the Baroque, its drama is muted and humane. De la Tour’s chiaroscuro is a language of slow planes and careful edges rather than of violent contrast. Sebastian’s body is carved by long gradients, his skin glowing where life persists, dimming where shadow gently recedes. The red of Irene’s headscarf and the attendant’s sleeves collects into deep clots rather than flaring. Even the darkest passages breathe; one senses air around the figures. The result is a scene whose power stems from concentration rather than shock, from the discipline that compassion requires.

The Role of Irene and the Ethics of Touch

Irene’s gesture is the fulcrum of the painting. Her right hand opens, palm up, in an invitation to surrender the wound to care; her left hand, just behind, prepares to act. There is no theatrical pity, no recoiling horror. She tends to the wounded as one familiar with both pain and cure. The face, slightly bowed and serenely intent, belongs not only to a saint but to a practiced nurse. De la Tour uses her presence to redefine sanctity as competence and steadiness, sanctifying the small, repetitive movements by which bodies are kept alive.

The Candles and the Attendant as Liturgical Instruments

The woman kneeling with the bound candles makes the scene possible. She is acolyte and assistant, her light both practical and ritual. The cluster of candles—frequently seen in funerary or vigil settings—reads here as a portable altar, an acknowledgment that care is sacred work. The attendant’s gaze is lowered, her posture compressed into a module of reliability. The rolled cuff at her wrist catches a bright lip of light, a detail that converts a garment into a tool. Even the candle wax, warmed and slightly translucent, becomes a material echo of flesh, repeating the painting’s central empathy.

The Nude as Vulnerability, Not Display

Baroque painters often revel in Sebastian’s athletic nudity. De la Tour refuses sensual exhibition. The saint’s body is neither a sculpture to admire nor an anatomy lecture; it is a person to be rescued. Skin tone modulates with restraint, the torso’s modeling soft rather than glossy. The loincloth is plain and functional. The arrow’s shaft is painted with the same respectful specificity as a rib or tendon—no fetishizing of the wound, only truthful description. This refusal of spectacle is central to the painting’s moral force: vulnerability is acknowledged without being consumed.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

The palette is a warm consonance of wine reds, rich browns, and honeyed flesh tones cooled only by the candle’s pale flame. Irene’s black robe absorbs light, stabilizing the composition; her crimson mantle and the attendant’s red sleeves carry the heat of devotion across the scene. The stone or plaster wall behind the figures keeps to an earthy neutrality, lending the flame and skin their authority. Because color remains restrained, emotion feels grounded. The painting’s world is real enough for care to be plausible and spacious enough for prayer to be intelligible.

Texture and the Truth of Surfaces

De la Tour persuades by letting matter behave exactly as we know it does in lamplight. Wax shines at the edges and dulls where melted; linen cuffs glow with a chalky brightness; flesh accepts warmth with a living, matte radiance; wood and wall absorb light with slow appetite. Even the steel of the arrow holds one lucid highlight at its bevel before sliding into shadow. These textures make the invisible—mercy, resolve, tenderness—credible. Because surfaces are true, the scene’s inner life is trustworthy.

Space, Silence, and the Architecture of Night

The setting is spare: a rough interior, perhaps a courtyard or a room with a heavy curtain. There is no cityscape, no Roman architecture, no crowd. The elimination of anecdote is purposeful. De la Tour builds a chamber in which only necessary things remain: bodies, flame, cloth, wood, and the small zones of air between hands and wound. The silence is almost sonic; one can imagine the faint hiss of candle, the whisper of fabric as Irene bends, the shallow breaths of the injured. This carefully rationed space dignifies the action and trains the viewer to the same attention the figures practice.

Time and the Interval of Care

The painting occupies the hinge between injury and recovery. The arrow is still in place, so treatment has just begun; faces are focused but unhurried. Time is not dramatized as catastrophe; it is expanded into an hour where each movement counts. De la Tour prefers this “present continuous”—the duration in which craft lives. In this respect the scene is more faithful to life than many martyrdoms: after the noise of violence comes the long work of tending, which seldom earns a crowd but often earns survival.

Iconography and the Plague Imagination

Seventeenth-century viewers, repeatedly struck by plague, would have recognized Sebastian as a civic patron. The arrow, often read as the disease that “pierces” a population, becomes in de la Tour’s hands both an emblem and a literal problem to solve. Irene’s calm suggests the practiced charity of plague nurses and confraternities that organized vigils for the sick. Candles were central to those rituals, markers of presence and prayer by the bedside. The painting thus resonates as both sacred narrative and contemporary documentary of how communities meet crisis: by showing up with light, cloth, steady hands, and learned gestures.

Dialogues with De la Tour’s Other Nocturnes

This work converses with the artist’s candlelit corpus. In the “Magdalene” series, light regulates introspection; in “St. Joseph, the Carpenter,” a child’s lamp makes work possible; in “Adoration of the Shepherds,” shared light gathers a community around a newborn. Here, illumination orchestrates triage. The same discipline prevails—few props, large planes, silence—but the stakes are medical as well as spiritual. The painting also aligns with de la Tour’s preference for women as agents of care and order; Irene’s authority recalls the Virgin teaching, Magdalene discerning, or a mother guiding a child’s prayer.

The Ethics of Looking

De la Tour positions the viewer slightly below Irene’s hand and outside the arc of her reach. We are permitted to witness but not to intrude. There is no invitation to gawp at pain, only to recognize the dignity of attention. The flame’s glow defines the boundary of our participation: we may stand within its circle and lend our gaze to the work, or we may remain in the shadows and let others tend. The painting becomes an ethics lesson for spectatorship, insisting that looking should assist care rather than consume suffering.

Technique, Edges, and the Persuasion of Planes

The picture’s authority comes from the nearly sculptural handling of forms. Edges are sure where substance is firm—the arrow’s shaft, the candle bundle, the hard oval of a shoulder—and softened where flesh turns or fabric folds. Sebastian’s torso is built from lucid planes that meet with the inevitable geometry of bone; Irene’s veil carries a single clean ridge of light that describes its weight. Glazes deepen the shadows without killing them; lean scumbles enliven flat walls so darkness never feels dead. Brushwork hides itself in service of the scene’s quiet.

Gesture and the Body’s Intelligence

Every figure contributes a distinct vocabulary of gesture. The kneeling attendant’s hands encircle the candles with practical intimacy, thumb pressed against wax like a craftsman’s clamp. Irene’s hand opens into a receptive cup, then bends into a precise tool; the grief-stricken observer at right covers her face, a gesture that closes the feedback loop of pain without stealing attention. Sebastian’s left arm droops with the weight of fatigue; his right hand curls inward as if seeking a grip on consciousness. These gestures are not theatrical signs but the body’s natural intelligence, and their accuracy is part of the painting’s persuasive power.

Color as Theology of Warmth

The theological content of the work is carried by color no less than by iconography. The warmth that spreads from the candles into red sleeves, into flesh, into the soft brown of wood and wall is a visible metaphor for charity. The deepest black, lodged in Irene’s robe, is not emptiness but a reservoir from which a small red belt and a pale veil emerge. In chromatic terms, mercy is the controlled distribution of heat; light teaches matter how to feel again.

Reception and the Turn from Martyrdom to Mercy

Compared to the rousing spectacle of other Baroque martyrdoms, de la Tour’s painting might seem understated. Its endurance rests on that understatement. By exchanging public heroics for private service, it anticipates later sensibilities that prize the nurse’s calm, the doctor’s triage, the volunteer’s steady presence. Viewers across centuries find in Irene’s poise and the attendant’s competence a model for action in times of illness, war, or disaster. The work has become emblematic of the idea that sacredness belongs as much to those who bind wounds as to those who suffer them.

Modern Resonance

The scene reads fluently in contemporary rooms. Replace the arrows with trauma of any kind, and Irene’s gestures remain recognizably modern—leaning in, lighting the space, organizing help. The bound candles rhyme with the flashlights and battery lamps of our own emergencies; the rough interior resembles the improvised wards erected in crises. De la Tour’s choice to show the interval of care rather than the height of violence invites viewers who serve—nurses, parents, neighbors—to see their labor dignified on a grand, quiet stage.

Conclusion

“St. Sebastian Tended by St. Irene” refines the Baroque vocabulary into a language of mercy. Composition channels the eye from flame to wound to caring hand; light becomes instrument and blessing; color keeps the climate warm enough for life to be reclaimed; texture convinces the senses that bodies and materials are real; gesture teaches how compassion acts. The painting asks for the same virtues it depicts: patience, steadiness, and focus. In the radius of a small flame, de la Tour gives back to martyrdom its most human chapter—the hour when suffering meets competence and darkness learns how to share its room with hope.